Amongst the glories of Winchester Cathedral, there is a chantry chapel of outstanding beauty and magnificence. The man who is buried there, and for whom the roof bosses provide a rebus clue, is Thomas Langton, who died of plague in 1501 only days after being elected by Henry VII as Archbishop of Canterbury. Earlier, he had served as the Bishop of Winchester (1493-1501), Salisbury (1484-93) and St. David’s (1483-84), and acted as a servant to three — or four, depending on how you count — English kings. As the information plaque at Winchester Cathedral succinctly announces, Langton had been a chaplain to Edward IV and Richard III, and Ambassador to France and Rome.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Although his death came as a surprise in his 70th year, he did have the opportunity to make an extensive will, showing he died a very wealthy man. It runs to over 100 items, and contains monetary legacies amounting to £2000, including the provision of six exhibitions in Queen’s College, Oxford, and more than a dozen other benefactions to the universities. Richard Pace (d. 1536), the future diplomat and Dean of St Paul’s, who had been sent as a young man to study at Padua at Langton’s expense, remembered that the bishop ‘befriended all learned men exceedingly, and in his time was another Maecenas*, rightly remembering (as he often said), that it was for learning that he had been promoted to the rank of bishop’. *Maecenas is a man who is a generous patron, especially of arts and literature.

It was “for learning” that Langton achieved his fame and reputation as an able diplomat, a proponent of the New Learning or Studia humanitatis, and one of the preeminent educators of his day. He was born in Appleby, Westmorland around the year 1430 to an obscure family that had no social prestige or any apparent political leanings. No nobleman is mentioned in his will or within his household, and none of his ancestors receive mention in the lists of household retainers of the great northern lords.

Despite his humble origins, he graduated with a Masters of Art degree from Cambridge University by 1456 and was a fellow of Pembroke College by 1462–3, where he served as senior proctor. He vacated his fellowship in 1464 to study at Padua University in Italy, but soon returned to Cambridge because of a shortage of funds, receiving a Bachelor of Theology in 1465. During his second stay in Italy, from 1468-73, Langton was created a Doctor of Canon Law at Bologna University in 1473 and Doctor of Theology by 1476. In 1487, he was elected Provost of Queen’s College, Oxford, becoming one of its greatest benefactors. As Bishop of Winchester, he started and personally supervised a school in the precincts of the bishop’s palace, where youths were educated in grammar and music. He was a good musician himself, and took talented musical children into his tutelage. It has been said he would study the various dispositions of the pupils, and would examine them at night on their day’s work, “always on the look-out for merit, that by encouragement it might be made more”.

-

-

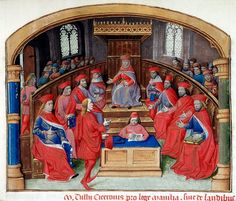

Chantry chapel of Thomas Langton, Winchester Cathedral

-

-

Chantry of Thomas Langon, Roof showing ceiling bosses “spelling out” his name (paint colors are historically accurate)

-

-

Chantry chapel of Thomas Langton, Winchester Cathedral

Aside from this, Langton is probably best known for a letter he wrote which included some remarks about Richard III. In September, 1483, he was part of the retinue which accompanied the newly-crowned king on his royal progress from London to points west and north, and observed the following:

He contents the people where he goes best that ever did prince; for many a poor man that hath suffered wrong many days have been relieved and helped by him and his commands in his progress. And in many great cities and towns were great sums of money given him which he hath refused. On my troth I liked never the conditions of any prince so well as his; God hath sent him to us for the weal of us all. . . .

As Keith Dockray observed, private letters like Langton’s are an “important quarry of information for the era of the Wars of the Roses”. They often can be dated precisely, helping historians to pinpoint the timing of key events. Moreover, since private letters are not written with a conscious attempt to record events for posterity or to promote official political propaganda, they offer a less filtered and more candid commentary on contemporary issues. As such they are valuable supplements to official records and chronicles of English history.

But letters have flaws, too, and those drawbacks can’t be ignored. People can lie, exaggerate, or speculate in their private correspondence. They can describe events they haven’t seen first-hand. They can create or spread vicious rumors and hearsay. Or, they can give unwarranted praise for an individual, or describe an event or issue not as an objective bystander, but as a partisan or someone with prejudices. Historians therefore don’t accept as true everything said in letters, so they submit them to an analysis of whether they should be deemed reliable or dismissed, in whole or part.

Langton’s September 1483 letter has received critical appraisal by historians over the centuries. The “conventional wisdom” was expressed by Professor Charles Ross in his 1981 biography of Richard III:

Langton was scarcely an impartial witness. A Cumberland man who had risen in Richard’s service, he had only recently been promoted to the see [bishopric] of St David’s during the Protectorate, and was soon to receive Lionel Woodville’s much richer see [bishopric] of Salisbury when the latter fled into exile in the aftermath of the 1483 rebellion. He had a natural and inbuilt interest in seeing Richard succeed.

The assertion that Langton’s account is “that of a partisan, and likely to be tinged with partiality” goes back to 1827 when J.B. Sheppard transcribed and wrote the introduction to The Christ Church Letters: A volume of mediaeval letters relating to the affairs of the priory of Christ Church Canterbury. That the preeminent scholar on Richard III wrote in 1981 a sentiment that was expressed 150 years earlier shows the tenacity of certain viewpoints. But more importantly, lying beneath Sheppard’s conclusion is the irreconcilable idea that a man of Langton’s qualities could actually praise someone who in his mind is a manipulative usurper. To Sheppard, “it is to be deplored” that he should fall into such naiveté. But this begs the question: who is being naïve? Can an historian objectively assess Langton’s letter if s/he views Richard III as being essentially repellant or heroic?

Because of this potential pitfall, we could look to other methodologies that divorce the historian from his or her own prejudices. Scientific laboratory analysis of Richard III’s skeletal remains, for instance, has already helped separate fact from fiction. This multi-disciplinary approach has debunked myths about his spinal deformity and appearance. Similarly, there is a methodology for judging the credibility of what Langton said in his letter. It comes from our courts of law where, every day, juries are instructed to apply a number of factors to sort out believable from unbelievable testimony:

Preliminary Instructions – Credibility of Witnesses

In deciding what the facts are, you may have to decide what testimony you believe and what testimony you do not believe. You are the sole judges of the credibility of the witnesses. “Credibility” means whether a witness is worthy of belief. You may believe everything a witness says or only part of it or none of it. In deciding what to believe, you may consider a number of factors, including the following:

(1) the opportunity and ability of the witness to see or hear or know the things the witness testifies to;

(2) the quality of the witness’s understanding and memory;

(3) the witness’s manner while testifying;

(4) whether the witness has an interest in the outcome of the case or any motive, bias or prejudice;

(5) whether the witness is contradicted by anything the witness said or wrote before trial or by other evidence;

(6) how reasonable the witness’s testimony is when considered in the light of other evidence that you believe; and

(7) any other factors that bear on believability.

Model Jury Instruction 1.7.

While these factors are used to weigh evidence in criminal and civil trials, they are also extremely useful in analyzing historical accounts like Langton’s letter. Indeed, historians apply some or all of them without realizing it. Charles Ross and J.B. Sheppard, for instance, rely exclusively on factor (4) to conclude that Langton was a biased partisan who would be motivated to see Richard III in the most favorable light. The reader is thus left with an incomplete analysis, since there is little or no attempt to apply the other items.

The goal of this essay is to give Langton’s letter a more thorough analysis by applying all the factors that determine a witness’s credibility. By doing so, we will discover much more about Langton’s life than is usually described in history books, and we will see emerge a picture that is quite different from the one painted by Ross and Sheppard. But before we do this, we first need to read the entire letter and understand its context.

From Thomas Langton, Bishop of St. David’s, to the Prior of Christ Church (September 1483)

My Lord I recommend one to yow, &c. If ther hap to be ony shippis at Burdeaux at such tyme as your wyne yt shalbe clear shippyd, the Kyng wil for no thyng graunte licence to yow, ne to non other, for to ship your wyne in a straunger. If ther be non Ynglyssh shippis, ye may well in that cace ship your wyne yn a straunger; ther ys no law ne statute ayeyn it; and so by thadvyce of the chef juge, Sir Fayreford Vavasor, Sir Jervas Clifton, and Medcalf you nedys no license; and so thai all shewyd the law. In this matter this ys the conclusion; in oon cas yow nedys no licence; in the other the Kyng wil noon graunte. The Kyng hath at this tyme ij messengers with his cosin of France. If thai bring home good tithings I dout not but the Kyng will wryte to his said cosin as specially as he can for your wyne; if he have no good tythings yow must have paciens; but how so ever it shal be send Smith your servant for your wyne, for I dout not but ye shal have it this yer. I pray you do so mych for me to take your servant iiij li. Or els pray master supprior to do it, to such tyme that y shal com to London, and pray your said servant for to by me ij tun of wyne with it, and bring it home with yours. I trust to God ye shal here such tythings in hast that I shalbe an Ynglissh man and no mor Welsh—Sit hoc clam omes. The Kyng of Scots hath sent a curteys and a wise letter to the Kyng for [h]is cace, but I trow ye shal undirstond thai shal have a sit up or ever the Kyng departe fro York. Thai ly styl at the siege of Dunbar, but I trust to God it shalbe kept fro thame. I trust to God sune, by Michelmasse, the Kyng shal be at London. He contents the people wher he goys best that ever did prince; for many a poor man that hath suffred wrong many days have be relevyd and helpyd by hym and his commands in his progresse. And in many grete citeis and townis wer grete summis of mony gif hym which he hath refusyd. On my trouth I lykyd never the condicions of ony prince so wel as his; God hathe sent hym to us for the wele of us al neque . . . . voluptas aliquis regnat . . . . . . . . . . . .

Our Lord have you in his kepyng. I wold as fayn have be consecrate in your chyrch as ye would have had me your

T. LANGTON.

It shal be wel do that your servant bring a certificate from the Mayr of Burdeaux that ther was no sheppis ther of Ynglond at such tymes as he ladyd your wyn.

To my Lord the Prior of Cryschyrch of Canterbury.

In order to understand the letter, we need to know three things: (a) to whom was he writing? (b) what was the nature of their past correspondence? and (c) what were the events that prompted this particular letter?

Who was the Prior of Christ Church and Why was Langton Writing to Him?

The Prior of Christ Church in Canterbury was William Selling. Like Langton, he came from an obscure family, studied in Italy, supported the New Learning, and collected books. Selling is considered one of the early Renaissance figures of England and several of his Latin orations are still extant; particularly notable is the speech he prepared for the convocation of 19 April 1483, cancelled by Edward IV’s death and funeral. Selling and Langton were the same age, both born circa 1430, and first met in Italy where Langton was pursuing a doctorate of canon law. Selling was a Benedictine monk at the time, but would become prior of Christ Church in 1472.

The two lived through the turmoil of Henry VI’s mental incapacitations and the power struggles that accompanied them, the defeat of the House of Lancaster at Towton in 1461, the early uncertainties of Edward IV’s Yorkist reign, the Kingmaker’s 1469 defection, Henry VI’s readeption and demise in 1471, and the crises brought about by the king’s sudden death in April, 1483. With so many shared experiences, they must have had a natural kinship. This is reflected in Langton’s statement that “I wold as fayn have be consecrate in your chyrch as ye would have had me”. Indeed, just a year earlier, Selling gave Langton the prestigious rectory of All Hallows Gracechurch in London, so presumably he reciprocated Langton’s affection.

They had been corresponding to each other for at least half a decade. In a letter written by Langton to Selling and dated the last day of the 1478 Parliament, we learn that Selling composed a sermon for convocation and had asked Langton to deliver it. Langton explains that Edward IV had assigned him to deal with Spanish ambassadors on “weighty” matters and regrets he might not be available to do so. He inquires after Master T. Smyth (presumably the same servant mentioned in the September 1483 letter) and then interjects “Ther be assignyd certen Lords to go with the body of the Dukys of Clarence to Teuxbury, where he shall be beryid; the Kyng intendis to do right worshipfully for his sowle.” He conveys the news that he was recently made Treasurer of Exeter Cathedral and states how much income he will derive from that office. He hopes Prior Selling shall be receiving “his wine” soon. The letter shows a mix of current events, personal news, and concern for a good friend.

What is the letter of September 1483 talking about? And what’s the big deal about “the wine”?

The letter written by Langton in September 1483 falls along the same general lines as the one from 1478, being a mix of current political events and personal news. More than half the content deals with the issue of “Prior Selling’s wine” and how to get it shipped from Bordeaux without incurring import taxes. Wine was not a frivolity but a major concern for the Canterbury priory; it was expensive and it was needed for the communion sacrament. In 1179, King Louis VII of France made a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas à Becket in Canterbury and in gratitude made a bequest in perpetuity for an enormous quantity of French wine (1,600 gallons per year) to the monks of Christ Church Priory. With the English invasion of France during the Hundred Years War, the French stopped honoring this grant, possibly because of the despoiling of their northern vineyards. When Langton was sent to France in 1477 as Edward IV’s ambassador, Selling gave him a petition along with instructions to do his utmost to press Louis XI (“the Spider King”) for a favorable answer on acknowledging the grant. As a result of Langton’s efforts, the French king not only committed himself to honoring the grant again, but he also stipulated that the wine would come from the Loire Valley – the best quality of wine produced in France. Langton’s achievement was memorialized in Canterbury’s records, and he was offered the living of St. Leonard, Eastcheap — an offer he declined in favor of accepting a future benefice. He’d end up waiting five years for that to happen. If anything, Langton was a very patient man.

In September 1483, with the accession of Richard III, the grant was still in operation but its future was uncertain, especially since the French had a new king in the person of Charles VIII. Langton reports to Selling that King Richard had sent two messengers to King Charles, ostensibly for the purpose, among others, of seeing whether the new French king would honor the grant of wine. Langton assures his friend that King Richard will personally write to Charles if necessary. However, the immediate concern for Selling was how to get his wine shipped out of Bordeaux without paying duties or a license to import. This was why Langton conferred with several judges and lawyers on the matter; their consensus was that Selling did not need a license to import and would not have to pay duties, even if the wine was carried aboard French ships. Langton then asks a favor: could Selling’s man buy two tuns of wine in France for him and have it shipped along with the Prior’s wine? Posterity does not record whether Selling agreed to this, but the upshot is that Langton was looking to evade paying duties by having his wine commingled with Selling’s duty-free cargo. One can be certain that Langton didn’t intend this letter to be read by the king’s agents.

The remainder of the September 1483 letter deals with how the new English king is being perceived on royal progress, Langton’s personal aspirations, and the situation with Scotland. Langton reports that the Scottish siege of Dunbar is still on-going, and he hopes the English will prevail in their occupation of that fortress. While the “Kyng of Scots” sent a courteous and wise letter about it, Langton believes some kind of confrontation between the two monarchs will occur, in the form of a “sit up” (i.e., diplomatic parlay) while King Richard is at York.

One of the more curious things about Langton’s letter is when he breaks into Latin, which happens twice. The first time is when he says “I trust to God ye shal here such tythings in hast that I shalbe an Ynglissh man and no mor Welsh—Sit hoc clam omes”. This sentence has been interpreted to mean that Langton aspired to be translated from St. David’s to an English bishopric in the foreseeable future — but let this be secret from everybody.

The second use of Latin is more puzzling, and is confounded by the illegibility of the original document which is partially damaged by damp. In 1827, Sheppard transcribed Langton as saying: “On my trouth I lykyd never the condicions of ony prince so wel as his; God hathe sent hym to us for the wele of us al neque . . . . voluptas aliquis regnat………” Alison Hanham made another attempt in 1975 to decipher this portion of the letter, reporting that she was assisted by a Miss Anne M. Oakley, Canterbury Cathedral’s archivist who looked at the manuscript under ultra-violet light. Hanham’s transcription reads: “Neque exceptionem do voluptas aliqualiter regnat in augmentatia” This, she translates into English as “Sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent, but I do not consider that this detracts from what I have said”. Hanham finds this observation to be consistent with the Crowland chronicler’s comments about Richard III’s court, where it was said too much attention was paid to singing and dancing and to vain exchanges of clothing, provoking the outrage of the people, the magnates and the prelates.

Viewing the totality of Langton’s relationship with Selling, the general tenor of his correspondence, and the things discussed, one can safely say they were intimate colleagues who were keenly interested in political developments and were genuinely interested in the other’s welfare. Selling entrusted Langton to deliver his sermon in convocation, to negotiate a sensitive issue with Louis XI about a lapsed grant, and to get a legal opinion about shipping his wine. With the accession of Richard III, Selling could reasonably expect to be called upon to write a sermon for the next convocation, as he had done for the one canceled April, 1483. Getting an accurate temperature reading on the new king and the political climate would be critical to that task. So the question becomes whether Selling could trust the credibility of Langton’s observations about the king, and this brings us to applying the legal methodology set out above.

Application of Witness Credibility Factors

(1) Did Langton have the opportunity and ability to see, hear, or know the things he wrote about Richard III?

Langton was remarkably well-placed to have first-hand observations about Richard III and the events of 1483. Not only was he present with the new king during his royal progress, but he was also living in London after returning from a diplomatic embassy to France in December 1482. As Rector of All Hallows Gracechurch, Langton’s parish included the Tower and Baynard’s Castle. This put Langton in close proximity to the events occurring at the Tower, and it made Richard a parishioner of Langton’s while he lived at Baynard’s as Lord Protector, and where on 26 June 1483 he was offered the crown. Moreover, it is quite likely that he was called to consult Edward V’s and Richard III’s royal councils on matters concerning foreign policy with France; Langton had made numerous diplomatic trips to the court of Louis XI and could provide valuable insights. As Langton’s biographer D.P. Wright notes, whenever Langton wasn’t on embassy “he was busy at court”. Since the administrations of Edward V and Richard III were notable for their continuity with Edward IV’s, there’s no reason to believe Langton suddenly found himself ostracized from court.

Langton participated, to some extent, in the coronation rituals of Richard III. He is mentioned in an indenture made between the king and Abbot of the Collegiate Church of St. Peter, Westminster, dated July 7, 1483. There, Langton and the Bishop of St. Asaph’s conveyed to the Abbot’s possession the reliquary ampule of St Becket’s oil that had been used during the king’s anointment. From this, historians believe Langton might have also participated in the procession carrying the ampule on the Vigil before coronation.

We can therefore conclude that Langton had an excellent opportunity to observe Richard’s conduct as Lord Protector and as king. But did he have a basis to measure Richard against other princes? Here again, Langton had a wealth of experience to draw upon. During his diplomatic embassies to Spain, France, and Burgundy, he met King Ferdinand, Duke Maximilian, and Louis XI. Indeed, Langton had several private audiences with the “Spider King”, including one in 1479 when Louis dismissed everyone from his palace so he could speak to Langton in absolute privacy. And, of course, Langton had ample experience with Edward IV and his courtiers, through six years of service to his administration. So when Langton states “On my troth I liked never the conditions of any prince so well as his”, it’s coming from a man who draws from a deep well of past experience with Europe’s and England’s most powerful leaders.

(2) How good was Langton’s understanding and memory of the events he spoke about?

Unlike Dominic Mancini, Langton was a native-born Englishman who understood its vernacular language and customs. In 1483, he was 53 years old with no apparent defects in his memory or acuity; he would go on to be elected Archbishop of Canterbury at age 70 so he must have had his “senses” even at that advanced age.

More importantly, Langton wrote his letter contemporaneously with the events he was reporting about. Contemporaneous writings are generally more reliable than those written “in hindsight”. The problem with hindsight is that it tends to view past events as fitting into pattern or being consistent with a result occurring much later. Many of us are familiar with the phrase “Monday morning quarterback” in American football, where a quarterback’s decision to throw a pass is criticized if it was intercepted and/or contributed to his team’s ultimate loss of the game. Most of us agree it’s not entirely fair to judge someone like that because the loss of the game was dependent on more variables than just one pass.

The same applies to historical chronicles, such as the Abbey of Crowland’s Continuations (aka “Crowland Chronicle”). Written by an unknown cleric in 1486, the chronicler assesses Richard III’s reign a year after his death at Bosworth. He views this outcome as evidence of God’s judgment on a usurper, murderer of nephews, and evil king. And while the Continuator tries to be as fair as possible, he cannot resist judging an event, or people, by the future consequences. When, for instance, the assembled English lords took an oath in February 1484 recognizing Richard III’s son as heir to the throne, the Crowland Chronicler views the son’s death in April as evidence that the oath was futile and was an “attempt of man to regulate his affairs without God”. The Crowland Chronicler observes this about Richard III’s royal progress to York in September 1483:

“Wishing therefore to display in the North, where he had spent most of his time previously, the superior royal rank, which he acquired for himself in this manner, as diligently as possible, he left the royal city of London and passing through Windsor, Oxford and Coventry came at length to York. There, on a day appointed for the repetition of his crowning in the metropolitan church, he presented his only son, Edward, whom, that same day, he had created prince of Wales with the insignia of the gold wand and the wreath; and he arranged splendid and highly expensive feasts and entertainments to attract to himself the affection of many people. There was no shortage of treasure then to implement the aims of his so elevated mind since, as soon as he first thought about his intrusion into the kingship, he seized everything that his deceased brother, the most glorious King Edward, had collected with the utmost ingenuity and the utmost industry, many years before, as we have related above, and which he had committed to the use of his executors for the carrying out of his last will.”

Langton’s letter of September 1483 was not written with foreknowledge of Richard III’s eventual death at Bosworth, or even the rebellion that would be put down in November. Instead, it is offered as an appraisal of the king during his first two months on the throne, and rendered after the controversial way in which he acceded to the crown. What’s interesting is how Langton describes a different version of why the king was so popular with the people; it’s not for the “splendid and highly expensive feasts and entertainments” alone, but because “many a poor man that hath suffered wrong many days have been relieved and helped by him and his commands in his progress”. Langton’s account also differs from the Crowland Continuator’s statement about Richard III’s rapacity for acquiring wealth. The king, Langton observes, refuses the tributes and gifts of money offered to him. While we needn’t toss out the entirety of the Crowland chronicler’s observations, we can concede that Langton’s account is given without the 20/20 hindsight possessed by an unknown cleric in East Anglia.

(3) How did Langton offer his information?

The information offered in Langton’s letter to Selling has two features. It was given in privacy (“Sit hoc clam omes” – let this remain secret from everybody) and it tries to be objective. The first item has received little recognition in historical journals. Compared to Mancini, who was being paid for his service and therefore would have a motive to exaggerate the significance of the rumors he heard on the street, Langton had nothing to prove or to gain, financially or otherwise, by telling Selling a slanted view of the king. And Langton did not report only the good things about Richard III. He broke into Latin to tell Selling that he thought “Sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent, but I do not consider that this detracts from what I have said”.

(4) Did Langton have any personal interest, bias, or motivation in seeing Richard III’s reign only in a positive light?

This is the area where most historians attack Langton’s credibility and objectivity. As Charles Ross asserts, Langton is biased in three ways: he is Northern and thus would favor a king from the North; he “rose up” under Richard and thus would naturally want the “gravy train” to continue; and he was favored by the king for translation to a more august English bishopric.

It is true that Langton was born in Appleby, Westmorland County, in the northwest of England, and probably (but not necessarily) lived in the north for the first two decades of life. He then moved away and, for the next 30 years, was educated at Oxford, Cambridge, Padua and Bologna, traveled extensively, and served on multiple diplomatic embassies on the continent. A fondness for his birthplace is evident by the way his last will and testament provided for his deceased parents’ chantry chapel there; for his own tomb, he chose Winchester Cathedral. Whether this background translated into a bias for men from the North is not entirely borne out. The most any historian has said on the subject is that, at the time of his death, his household had some individuals with the last names “Machell” and “Warcop” which are “redolent of Appleby and Westmoreland”.

The only favoritism displayed by Langton was for men “of learning” and youths showing talent musically or intellectually. He also promoted his nephews, Robert Langton and Christopher Bainbridge, to positions in the Church. Nepotism aside, Langton’s life and career shows striking neutrality. He served Yorkist and Tudor kings. He befriended men like William Selling, a Kentish man. Whether Langton even viewed Richard III as northern is open to question, as the king was not born or raised there, and did not show any early inclination to promote his northern ducal retainers into royal administration. We should also remember that the king’s royal progress moved through Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire, before arriving in Yorkshire. Langton’s observations are not limited to what he saw in York (“he contents the people wherever he goes”).

Langton was never a retainer of Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Rosemary Horrox, whose book Richard III: A study of service details the duke’s affinity, makes no mention of Langton whatsoever. Nor did Langton’s family have the level of patronage demonstrated by another Westmorland man – Richard Redman, Bishop of St. Asaph’s – who had several family members within Richard III’s northern affinity.

Thus, the idea that he “rose up” in Richard’s service is simply wrong. Langton first came to prominence under the reign of Edward IV. He appears to have been involved in the drafting of the Royal Household Ordinance of 1478, a set of regulations for the king’s household that were complementary to those in the earlier Black Book. Here, the warrant under the king’s signet, dated 9 July 1478, tells the chancellor that “we by thaduis [the advice] of oure counsell have made certain ordinaunces for the stablysshing of oure howshold which by oure commaundement shal be deliuered vnto you by oure trusty and righte welbeloued clerc and councellor, Maister Thomas Langtone” and directing the chancellor to “put alle the ordinaunces in writing seled vnder oure great sele, and the same so seled send vnto vs by oure said counsellor without delay”. From 1476 to 1482, Edward IV repeatedly employed Langton to serve on diplomatic embassies to Castile, France and Burgundy to negotiate matters of state, including the marriage of his children to foreign princes/princesses and the tortuous negotiations with France and Burgundy. For his efforts, Edward IV rewarded Langton by nominating him to the Treasurership of Exeter Cathedral and the rectory of Pembridge in Herefordshire. Langton probably wanted to see continuity between Edward IV’s administration, where he had a secure place, and the new regime, whether that be under Edward V or Richard III. It is likely that he, like many prelates and lords, saw Richard as presenting the best opportunity for that continuity.

Finally, there is Langton’s statement that he hoped to be translated to an English diocese in the near future (“I trust to God ye shal here such tythings in hast that I shalbe an Ynglissh man and no mor Welsh—Sit hoc clam omes”). For a man of Langton’s cosmopolitan qualities, the Bishopric of St. David’s was probably viewed as a stepping stone to greater benefices, rather than a final destination. Such was the case for Henry Chichele, John Catterick, and Stephen Patrington, who briefly served at St David’s before moving on to Canterbury, Coventry/Lichfield, and Chichester.

It was very early in the reign of Edward V that the Bishopric of St David’s became vacant. Richard Martyn had been elected to that position by Edward IV in April 1482, but died on May 11, 1483. As the newly-confirmed Lord Protector, Richard elected Langton whose service to Edward IV had been amply demonstrated. While he surely welcomed the bishop’s mitre, he had no connections whatsoever to Wales and it probably was not the best fit for a man with so many duties at the royal court. His predecessor, Martyn, claimed the Welsh diocese was impoverished, heavily in debt, and comprised of dilapidated buildings. It seems when Langton was given St. David’s a year later, the diocese was still so poor that some provision had to be made for him to keep his Pembridge rectory:

Harleian MS, Vol 1, p 35: dated May 1483, by Edward V: “Know that we of our special grace and mere motion have given and granted and by these presents give and grant to our dearly beloved and faithful clerk Thomas Langton custody of all the temporalities of the bishopric of St Davids . . . on account of the sincere love and affection which we bear and have to the person of our aforesaid dearly beloved counselor Thomas Langton clerk now elected to St Davids and considering that the goods benefices and also manors lands tenements rents and other possessions belonging to the same bishopric are so greatly diminished and reduced and suffer such dilapidation and ruin that the same now elect, when he takes upon himself the office of bishop, will not be able to support or maintain as he ought his state and dignity and other burdens incumbent on the honour of bishop, of our especial grace and of our certain knowledge and mere motion and in order that the same bishop elect may be able to support and maintain fittingly and honourable the state honour and dignity of the episcopate, we have granted and given licence for ourselves and our heirs that the same now elected may send and direct his proctor or proctors to the Roman curia and that they should make certain provision that the same elect after he has been consecrated to the bishopric of that place should be able to hold the parish church of Pembridge in the diocese of Hereford in our gift which said Thomas now holds….”

Like Martyn, Langton’s relationship with his diocese of St. Davids was distant and he left no imprint on its Register. He probably employed a vicar-general to administer the diocese and used a suffragan to deputise for him in his spiritual functions. Perhaps Langton had his eye elsewhere as there were other prelates who were of frail age (Thomas Bourchier, born 1411) or out of favor with Richard III (Thomas Rotherham, John Morton). If Langton wanted to be translated from St. David’s to an English bishopric, he’d have to be patient, wait for a vacancy to open up, and remain in favor with the king.

It seems there was one bishopric on the verge of being forcibly vacated: Lionel Woodville’s see of Salisbury. Woodville had been made bishop in 1482, and notwithstanding a brief interlude in June when he took sanctuary at Westminster Abbey with his sister the widowed Queen Elizabeth, he “did not play any significant part in the political crisis after Edward IV’s death in 1483”. Although absent from Richard III’s coronation, he apparently came to terms with the new regime, for he was named to the commission of the peace in Dorset and Wiltshire after Richard III’s accession. Some have suggested that Woodville personally welcomed Richard III in his role as Chancellor of Oxford University when the king visited Magdalen College on July 24-26, 1483. His last official act as Bishop of Salisbury is dated September 22, 1483, when he granted a commission to effectuate the appropriation of the chapel of St. Katherine, Wanborough, to Magdalen College, Oxford. He must have been under suspicion at this point, because Richard III ordered the forfeiture of his temporalities the next day. Perhaps Langton was aware of the king’s suspicions and knew that Lionel Woodville’s days were numbered.

The takeaway from all this is that Langton was certainly not a retainer of Richard III from his days as duke, had no strong pro-northern bias, and was realistically ambitious as a prelate looking for advancement to a more financially secure and less “dilapidated” bishopric. So, indeed, Langton was happy to see Richard III so well received. Did this influence his observations? Probably, but not to the extent that Charles Ross and others have suggested.

(5) Is there any evidence to contradict what Langton said in his letter, by his own hand or others?

While Langton did observe “Sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent, but I do not consider that this detracts from what I have said”, there is nothing in his letter that contradicts his statement about the king’s popular reception while on royal progress or the justice dispensed to the common people along the way. So his letter is internally consistent.

The only other contemporary observation about how the people received Richard comes from Mancini, in his December 1483 report to Angelo Cato. Read in its entirety, Mancini describes the London population as being ambivalent and turbulent with speculation about Richard’s true intentions. At one point, they are favorably impressed with a letter to royal council written by Richard in April 1483 before he arrived in London. In it, he declared his loyalty to Edward IV’s heir and asked council to take “his desserts” into consideration when disposing of the government, to which he was entitled by law, and his brother’s ordinance. “This letter had a great effect on the minds of the people, who, as they had previously favoured the duke in their hearts from a belief in his probity, now began to support him openly and aloud; so that it was commonly said by all that the duke deserved the government.”

Public opinion, however, would soon veer between support and distrust of the Lord Protector. After reports were received in London that Richard had taken Edward V into custody at Stony Stafford, “the unexpectedness of the event horrified every one. The queen and the marquess, who held the royal treasure, began collecting an army to defend themselves… But … they perceived that men’s minds were not only irresolute, but altogether hostile to themselves. Some even said openly that it was more just and profitable that the youthful sovereign should be with his paternal uncle than with his maternal uncles and uterine brothers.” Meanwhile, a “sinister rumor” was circulating that Richard had taken the young king into his possession so that he might usurp the crown. These rumors were met with more letters from Richard to council justifying his actions; when publicly read, “all praised the duke of Gloucester for his dutifulness toward his nephews and for his intention to punish their enemies. Some, however, who understood his ambition and deceit, always suspected whither his enterprises would lead.” When Richard entered the city with wagons filled with weapons to prove there was an attempt against his life, there were Londoners who disbelieved this and thought they came from storehouses of weaponry related to the Scottish war. “[M]istrust both of his accusation and designs upon the throne was exceedingly augmented.” When the public received news of a plot in the Tower and that its originator, Hastings, had “paid the penalty” by his execution there, Mancini writes that “at first the ignorant crowd believed, although the real truth was on the lips of many, namely that the plot had been feigned by the duke”. The public’s pattern of alternating between trust and distrust of Richard is Mancini’s essential point.

Mancini’s final observation about the public’s perception of Richard comes shortly after Hastings’ death. By this time, Richard is riding through London surrounded by a thousand attendants dressed in purple. “He publicly showed himself so as to receive the attention and applause of the people as yet under the name of protector; but each day he entertained to dinner at his private dwellings an increasingly large number of men. When he exhibited himself through the streets of the city he was scarcely watched by anybody, rather did they curse him with a fate worthy of his crimes, since no one now doubted at what he was aiming.” How Richard was perceived after his accession to the throne, however, is not part of Mancini’s report, as he concludes by saying: “These are the facts relating to the upheaval in this kingdom; but how he may afterwards have ruled, and yet rules, I have not sufficiently learnt because directly after these his triumphs I left England for France, as you Angelo Cato recalled me. Therefore farewell, and please show some mark of favour to our work, for whatever its quality, it has been willingly undertaken on your account. Once more farewell. Concluded at Beaugency in the County of Orleans. 1 December 1483.”

Mancini’s account of what happened in London in April, May and June 1483 does not match the glowing account of Langton given in September 1483. Can we explain this inconsistency? Yes. They cover different time periods so are not necessarily inconsistent; the public might have initially viewed Richard with wariness and hesitation, and then came to accept his rule in the months that followed. We also know that Mancini did not speak English, was relying on others to translate for him, was reporting hearsay and rumors. We have no way of knowing if he personally observed any of the events recorded. Nor do we know the identity of his sources for those events he did not witness. These “unknowns” do not necessarily disqualify his account but neither do Mancini’s observations disqualify Langton’s.

(6) How reasonable are Langton’s statements when considered in light of other evidence?

Langton’s statements find support in other contemporary primary sources. John Rous, when creating in 1483-84 his famous Warwick Roll, wrote that the Richard III ruled his subjects “full commendably” – punishing offenders, especially extortioners and oppressors of the common people, and cherishing those that were virtuous. By his “discrete judgment” he received great thanks and the love of all his subjects, rich and poor. Later, in his generally critical post-1485 assessment of the king, Historium Regum Angliae, Rous observed that when offered money by the peoples of London, Gloucester and Worcester, he declined it with thanks, affirming that he would rather have their love than their treasure.

Shortly after his coronation, Richard sat with his judges and had the following exchange, as reported in the Richard III Society’s website:

Richard was concerned about justice, both for the individual and its administration. A Year Book reports one of his most famous acts, when he called together all his justices and posed three questions concerning specific cases. This record provides an idea of Richard’s comprehension of and commitment to his coronation oath to uphold the law and its proper procedures.

The second question was this. If some justice of the Peace had taken a bill of indictment which had not been found by the jury, and enrolled it among other indictments ‘well and truly found’ etc. shall there be any punishment thereupon for such justice so doing? And this question was carefully argued among the justices separately and among themselves, … And all being agreed, the justices gave the King in his Council in the Star Chamber their answer to his question in this wise: that above such defaults enquiry ought to be made by a commission of at least twelve jurors, and thereupon the party, having been presented, accused and convicted, shall lose the office and pay fine to the King according to the degree of the misprision etc.’

Even Charles Ross, who characterized Langton as a partisan, finds support for his observations in contemporary records:

“[Langton’s] specific statements are supported by other evidence. That Richard turned down offers of benevolences from the towns he visited is confirmed by John Rous, one of the most hostile sources for Richard’s reign, and record evidence confirms a similar statement by John Kendall, the king’s secretary, that throughout his reign Richard was at pains to ensure the dispensing of speedy justice, especially in the hearing of the complaints of poor folk. In December 1483 John Harington, clerk of the council, received an annuity of Ł20 for ‘his good service before the lords and others of the [king’s] council and elsewhere and especially in the custody, registration and expedition of bills, requests and supplications of poor persons’; and that portion of the council’s work which dealth with requests from the poor, later to develop into the Tudor Court of Requests, received a considerable impetus during Richard’s reign.”

Given the number of corroborative primary sources, the observations contained in Langton’s letter are all the more reasonable and credible, rather than the product of a partisan’s over-enthusiastic “spin” on what he had witnessed.

(7) Any other factors that bear on believability.

Finally, we should determine whether Langton was unduly impressed by the pomp and ceremony of the royal progress, and whether he had demonstrated a good judgement of people in his life. Although from an undistinguished family, Langton was no stranger to pomp and ceremony – he’d traveled to the grandest courts in Europe and had witnessed their splendor. He was consecrated a bishop on September 7, 1483, a day before the investiture of the king’s son as Prince of Wales, which raises the interesting prospect that this may have been a part of the magnificent ceremonies that occurred in York. Langton, in his letter to Selling, described them a little disapprovingly as exemplars of sensual pleasure, so obviously he wasn’t that overawed.

One of Langton’s chief characteristics was that of a sincere educator, who placed a high priority on talent and intellect, rather than courtly display. As stated above, one of his students called him a Maecenas and, because of Langton’s patronage, was able to study in Italy and ultimately become the Dean of St. Paul’s. The student’s name was Richard Pace, and there is a lovely tale about how Langton discovered him:

There is happily a contemporary appreciation of [Thomas Langton] still extant. This occurs in a classical treatise of Richard Pace on the advantages of Greek studies, printed at Basle at the famous press of John Froeben in 1517. Pace began life as an office boy to the Bishop at Winchester. Langton observed his genius for music, and in the musician prospected the scholar: the boy was meant for greater things. Forthwith he packed him off to Padua to be taught Greek and Latin in the best school of the place, and paid all the expenses of his education. The work was still incomplete in 1500-1, at the Bishop’s death—Pace was then at the university of Bologna — but provision was made in his will for a further seven years’ study. The Bishop’s discernment was justified. Pace became distinguished in the New learning, and was a close friend of Colet and Erasmus, the latter of whom addressed to him a considerable proportion of his fascinating letters: he was employed by Henry VIII as private secretary, and, among a long list of ecclesiastical preferments, succeeded Colet in the deanery of St. Paul’s.”

Langton similarly went out of his way to support his nephews – but not all of them. He determined his nephew Robert Langton to be particularly talented and paid for his education in Italy, too. Robert went on to become a prebend at several cathedrals and a great benefactor to Queens College, Oxford. Langton seems to have had a good talent for discerning people’s abilities.

Conclusion

It is hoped that this analysis has elucidated some the arguments about the credibility of Langton’s September 1483 letter. Langton is a fascinating man not only because of his meteoric rise from a modest family, but also because of his avocation of the New Learning in England, showing that his homeland was not living in the “Dark Ages” while Italy was basking in the sun of the “Renaissance”.

Langton went on to serve Henry VII, but didn’t take an active part in his court, unlike fellow Westmorlander Richard Redman, Bishop of St. Asaph’s. There is some thinking that Langton was present at the Battle of Bosworth, being loyal to Richard III to the end, although there is no direct proof to confirm that. In the aftermath of Richard III’s death, he forfeited his temporalities as Bishop of Salisbury but by November 1485, had been restored to them. Henry VII first summoned him to parliament in 1487, and appointed him to commissions of the peace in Wiltshire, Hampshire and Surrey, which he served on through the end of his life. In 1493, Langton was translated to the wealthiest bishopric in England, that of Winchester where he now reposes in death. Despite this seal of approbation from the Tudor king, Langton continued to shun the court and focused on diocesan administration and on the musical education of children at his new school. Perhaps he had seen enough of princely politics. The rebus he adopted for himself, representing a “long tone” and featuring prominently in his chantry’s fan vaults, suggests he had turned his gaze to matters more musical and spiritual.

Sources & Further Reading

Books:

C.A.J. Armstrong (ed.): “DOMINIC MANCINI’S THE USURPATION OF RICHARD THE THIRD”, Oxford University Press (1936)

Keith Dockray: “RICHARD III: A SOURCE BOOK”, Alan Sutton (1997)

Rhoda Edwards: “THE ITINERARY OF KING RICHARD III 1483-1485”, Richard III Society (1983)

Louise Gill: “RICHARD III AND BUCKINGHAM’S REBELLION”, Alan Sutton (1999)

Alison Hanham: “RICHARD III AND HIS EARLY HISTORIANS 1483-1535”, Clarendon Press Oxford (1975)

Michael Hicks: “RICHARD III”, The History Press (2009 reprint)

Susan Higginbotham: “THE WOODVILLES: THE WARS OF THE ROSES AND ENGLAND’S MOST INFAMOUS FAMILY”, The History Press (2013)

Rosemary Horrox & P.W. Hammond (eds.), “BRITISH LIBRARY HARLEIAN MANUSCRIPT 433”, Alan Sutton (1979)

Rosemary Horrox (ed.): “PARLIAMENTARY ROLLS OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 1275-1504, RICHARD III (1484-85)”, Boydell Press (2005)

Rosemary Horrox: “RICHARD III: A STUDY OF SERVICE”, Cambridge University Press (1989)

R.F. Isaacson: “THE EPISCOPAL REGISTERS OF THE DIOCESE OF ST DAVID’S 1397-1518, VOLUME II”, Society of Cymmrodorion (1917), https://ia800302.us.archive.org/31/items/theepiscopalregi02unknuoft/theepiscopalregi02unknuoft.pdf (accessed 2 November 2016)

Paul Murray Kendall: “RICHARD THE THIRD”, W.W. Norton & Co. (1955)

A.R. Myers: “THE HOUSEHOLD OF EDWARD IV: THE BLACK BOOK AND THE ORDINANCE OF 1478”, Manchester University Press (1959)

Nicholas Pronay & John Cox (eds.): “THE CROWLAND CHRONICLE CONTINUATIONS 1459-1486”, Alan Sutton (1986)

Charles Ross: “RICHARD III”, University of California Press (1981)

John Rous, “THE ROUS ROLL”, Alan Sutton (1980, first published 1859)

Cora L. Scofield: “THE LIFE AND REIGN OF EDWARD THE FOURTH IN TWO VOLUMES”, Frank Cass & Co. (1967)

J.B. Sheppard (ed.): “CHRIST CHURCH LETTERS. A VOLUME OF MEDIAEVAL LETTERS RELATING TO THE AFFAIRS OF THE PRIORY OF CHRIST CHURCH CANTERBURY”, Camden Society (1887 reprint of 1827 original)

Anne F. Sutton & P.W. Hammond (eds.): “THE CORONATION OF RICHARD III: THE EXTANT DOCUMENTS”, Alan Sutton (1983)

Edith Thompson (ed.): “WARS OF YORK AND LANCASTER 1450-1485”, London (1892)

D.P. Wright (ed.): “THE REGISTER OF THOMAS LANGTON, BISHOP OF SALISBURY 1485-93”, Canterbury and York Society (1985)

Journals and Biographical Dictionaries:

Percival Brown: “Thomas Langton and his Tradition of Learning”, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, new series, Vol. xxvi (1926), pp. 150-246 [http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-2055-1/dissemination/pdf/Article_Level_Pdf/tcwaas/002/1926/vol26/tcwaas_002_1926_vol26_0007.pdf, accessed 19 August 2016]

Cecil H. Clough: ‘Selling , William (c.1430–1494)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004); [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4991, accessed 23 Oct 2016]

John Hare: “The Bishop and the Prior: demesne agriculture in medieval Hampshire”, Agricultural History Review, vol. 54, no. II, pp 187-212 [citations to M. Page, ‘William Wykeham and the management of the Winchester estate, 1366–1404’, in W. M. Ormrod(ed.), FOURTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND, vol. 3 (2004), p. 108]

Ken Hillier: “The Rebellion of 1483: A study of sources and opinions,” The Ricardian, (September 1982)

Rosemary Horrox: ‘Rotherham , Thomas (1423–1500)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/24155, accessed 23 Oct 2016]

Jonathan Hughes, ‘Martyn, Richard (d. 1483)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18236, accessed 27 Oct 2016]

David M. Luitweiler, “A King, A Duke, and A Bishop”, The Ricardian Register, Vol. XVIII, No. 4 (Winter, 2004), pp. 4-10.

John A. F. Thomson, ‘Woodville, Lionel (c.1454–1484)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004); online edn, Sept 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29938, accessed 23 Oct 2016]

Susan L. Troxell: “Rulers, Relics and the Holiness of Power: A review”, The Ricardian Bulletin (December 2014), pp. 55-57 (transcription of Westminster Abbey Muniments, 9482, 7 July 1483, relating to the reliquary oil of Thomas à Becket, by T. Erik Michaelson)

D.P. Wright: “Langton, Thomas (c.1430–1501)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004); online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16045, accessed 23 Oct 2016]

Other Sources:

“Richard By His Contemporaries”, from Richard III Society website, http://www.richardiii.net/2_1_0_richardiii.php (accessed 31 Oct 2016)

Model Civil Jury Instructions, District Courts of the Federal Court of Appeals, 3d Circuit (2010)

Overview – Federal Jury Instructions & Evidence, http://federalevidence.com/node/893/ (accessed 1 November 2016)

Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions, Superior Courts of New York