Putting aside the mystery of what ultimately happened to Edward IV’s two sons, one enduring difficulty for a student of history is whether Richard III used the proper legal procedure in having them declared illegitimate because of their father’s precontracted marriage to Eleanor Talbot. The most (and only) significant defect appears to be the failure to refer the issue to a church court for determination.[1] But it seems no one has fleshed out how an ecclesiastical tribunal would have litigated such an extraordinary and unprecedented matter, let alone identified which church court would have had authority to hear it.

As a retired litigator of 20 years, I undertook the challenge of researching medieval English church court procedures and precedent cases to answer four questions: Which church court would have decided the precontract issue? How would it have conducted the litigation? What evidence would it have heard? How conclusive would its decision have been? They seemed like simple questions, but they were not. Along the way, I learned not only about the unique relationship of English church and state when it came to addressing marriage and inheritance matters, but also about a thicket of procedural issues that an ecclesiastical tribunal would have presented in 1483, the sum of which may help explain why it wasn’t referred there in the first place.

A Claim that Involved Both Canon and Secular Law

The Crowland Continuator wrote that Richard III’s title to the throne was first put forward on 26 June 1483 when he claimed for himself the government of the kingdom and ‘thrust himself’ into the marble chair at Westminster Hall. The ‘pretext’ for his ‘intrusion’ was put forward by means of a supplication [petition] contained in a ‘certain parchment roll’ that Edward IV’s sons were bastards and incapable of succession, because their father had been precontracted to marry Lady Eleanor Butler [Talbot] before he married Elizabeth Woodville. The children of George of Clarence were also excluded from succession because of their father’s attainder.

Philippe de Commynes

The Crowland Continuator gives us no other details about what debate, discussion, or proof was produced to support the allegation, except to suggest that the petition originated in the North and was written by someone in London.[2] Dominic Mancini, who was living in London at the time, reported that certain ‘corrupted preachers of the divine word’ gave sermons about the illegitimacy of King Edward’s children, and that the duke of Buckingham supported those allegations by declaring the king had been precontracted to a foreign princess.[3] Philippe de Commynes wrote in his ‘Memoirs’ that it was Robert Stillington, bishop of Bath and Wells, who came forward and gave evidence from his personal knowledge about the precontract to Lady Eleanor and its consummation.[4] Ultimately, the Act of Succession known as Titulus Regius was enrolled in January 1484 during Richard III’s only parliament.[5]

Church courts were quite familiar with marital precontract claims and the resulting disinheritance of children, a scenario that seems to have arisen in pre-modern England with surprising regularity even in the lower social classes. Professor R. H. Helmholz detailed the frequency of such claims in his book Marriage Litigation in Medieval England and determined that they out-numbered straightforward divorce cases. The distant date of King Edward’s alleged precontract to Eleanor Talbot, and their inability to testify, although sounding suspicious or unfair to our modern sensibilities, were of no relevance. There were no applicable statutes of limitations, and a precontract claim could be raised after the deaths of the putative spouses. It was not unknown for someone to wait 20, 30 or even 50 years before enforcing a precontract or making a claim that a particular marriage was invalid. ‘This meant that established marriages could be upset by the stalest of [pre-]contracts.’[6] Claims that sought to declare a child illegitimate because of his parents’ invalid marriage were also more commonplace than we often understand, an artifact of the complex system of marriage and consanguinity rules, and the way that marriages could be formed clandestinely with a simple statement of present intent (both parties saying ‘I agree to marry you’ was sufficient in church law).

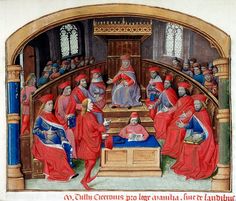

Church court

While church courts were endowed with the jurisdiction to determine whether a precontract existed or not, or whether someone’s children were illegitimate as a result, they had absolutely no power to determine who inherited their parents’ estate even if – and especially if — he was the potential king of England. By the fifteenth century, English legal practice was especially clear on this concept: the church courts only had jurisdiction to adjudicate who was a legitimate child from a legitimate marriage. Once it determined that the child was born outside a legitimate marriage, then it was left entirely up to the secular arm to determine what he or she would inherit from their parents. This derived from a primitive notion of the separation of church and state, and the idea that the rights of inheritance derived exclusively from feudal law. The Statute of Merton clearly made this point: no bastard child could ever be an heir to his father’s estate as a matter of English feudal law.[7] Therefore, it must be understood that even if the issue of the legitimacy of Edward IV’s children had ever been referred to a church court for determination, it had no power to say who should inherit the crown. That would always be for secular English law to determine.

Which Ecclesiastical Venue?

The first conundrum in 1483 would have been what court or tribunal to refer the matter to. Each bishop had a ‘consistory court’ for the purpose of hearing cases involving marriage and bastardy, and other matters exclusively within church law jurisdiction. Because of the volume of litigation, however, it was impossible for a bishop to attend to this function personally, therefore he appointed an ‘official’ or ‘commissary general’ to act as his representative in adjudicating disputes. In many dioceses, the dean, archdeacon, or chapter would also have their own courts. However, in matters involving elite personages or sensitive political issues, it was not uncommon for the bishop himself to mediate the dispute, as we can see from the bishop of Norwich’s personal involvement in trying to dissolve the scandalous marriage between Margery Paston and Richard Calle in 1469.

The consistory courts were staffed with judges, lawyers (‘proctors’) and barristers (‘advocates’), examiners to conduct witness interrogation, scribes, archivists (‘registrars’), and summoners (‘apparitors’ or ‘bedels’). No one was required to have a law degree, but most had some formal education in canon or civil law, especially the judges. Quite unlike common law English trials, there were no juries and no examination of live witnesses in open court. Instead, judges based their verdicts solely on the review of offered documents and written depositions which contained the answers given by witnesses to questions (‘interrogatories’) put to them by the examiners. Appeals could be taken either to the archbishop of Canterbury or of York, depending upon which Province the case had been filed in, or directly to the Pope via the Roman Curia. The archbishop of Canterbury’s appellate court was called the Court of Arches, located at St Mary-le-Bow Church in London, and was considered the premier ecclesiastical court in England having both original and appellate jurisdiction.

Court of the Common Pleas

Notwithstanding this church court infrastructure, it seems highly unlikely that the 1483 allegation of precontract would have been referred to a bishop’s consistory court or even to the Court of Arches. The matter touched directly on the royal family and on whom would become the next king of England. In looking for past precedents, the closest analogue is the ecclesiastical trial of Eleanor Cobham, wife of Humphrey Duke of Gloucester. Cobham was married to the uncle and heir-presumptive to Henry VI, and was in line to be queen-consort if the king died without children. In the summer of 1441, Cobham was implicated by members of her household in using magic to predict the death of the king. An indictment was brought forward in the King’s Bench against the household servants, and they were charged with sorcery, felony, and treason. Cobham was named as an accessory. While the secular courts had jurisdiction over charges of treason and felony, the church courts had jurisdiction over matters of heresy and witchcraft.

Rather than refer the matter to a bishop’s consistory court, the king’s council selected a group of prelates to act as an ecclesiastical tribunal to determine the truth of the allegations against Cobham and her punishment. No doubt this was done because of the shocking political implications of accusing the heir-presumptive’s wife of treasonable sorcery. The panel included the archbishops of Canterbury and York, the cardinal-bishop of Winchester, the bishop of Bath and Wells, the bishop of Lincoln, the bishop of London, and the bishop of Norwich. Most of these men were also part of the king’s secular government. Bishop Stafford of Bath and Wells was the king’s Chancellor. Cardinal Beaufort of Winchester, Archbishop Kemp of York, and Bishop Alnwick of Lincoln all currently sat on the royal council. Beaufort and Kemp, in particular, were known antagonists and opponents of Gloucester and his wife, and many saw the panel’s work as nothing more than a thinly-veiled attempt to destroy them and their political faction.[8]

Similarly, the political dimensions in 1483 were far too enormous to refer the matter of the princes’ illegitimacy to a single prelate or his court. (And what bishop would have wanted to have sole responsibility to decide such an inflammatory issue?) Therefore, if Cobham’s case is any precedent, it would seem that the only appropriate way to do so would have been for the royal council, of which the Lord Protector was the chief, to summon a group of prelates and men learned in canon law to hear it. And, just like the Cobham case, the membership on that panel could be perceived as having partisan agendas and rendering a biased decision.

How Would a Church Court Conduct the Litigation?

Church court procedure was usually divided into three stages: an opening hearing, the taking of evidence, and the reading of a judgment. The first stage required the party asserting the allegation of precontract to appear in person or by a proctor, in order to recite the specifics of the ‘citation’ or claim. The second stage involved the witnesses being identified by name and sworn in, and then taken outside of court to be interrogated separately and in private according to questions prepared by the parties and the judge. The testimony of each witness would be reduced to a written deposition, and then published (read aloud) on a date set by the judge. At that time, witnesses could be challenged or ‘exceptions’ made to their character or testimony. The last stage was for the judge to read all the depositions and review any documentary evidence, and then arrive at a decision. The parties could argue through their advocates that their side was the correct one, and even submit legal briefs to support their case. The judge was given wide latitude to arrive at whatever conclusion he deemed compliant with substantive canon law. He was not required to explain the reasons supporting his decision, and could proceed to a separate hearing on what punishment was appropriate under church doctrine. From the first hearing to the final judgment, the average lifespan of a typical marriage case was around 5-7 months.[9]

Would an ecclesiastical tribunal have followed this general procedure in 1483, and if so, would we have had the benefit of written depositions from Stillington or any other witnesses who would have testified about the precontract? To the latter question, the short answer is probably no. There exist no witness depositions or transcripts from Eleanor Cobham’s ecclesiastical trial, only the indictment filed against her servants in the King’s Bench records (what we do know about the Cobham trial comes from The Brut, and other London chronicles, not from official court or church records). Nevertheless, her case was generally divided into these three stages. After fleeing to Westminster Abbey for sanctuary, Cobham was cited to appear at St Stephen’s Chapel where she was examined on several points of felony and treason, which she strenuously denied, and was allowed to return to sanctuary. The next day, she was summoned to hear the incriminating testimony of a witness against her; she confessed to some of the charges and was transferred to Leeds Castle in Kent. A secular criminal law investigation was conducted into the three household servants, and it was determined that they – and Cobham — had celebrated a mass using elements of necromancy and sorcery in order to predict the death of Henry VI, an act of treason.

Cobham was next hauled before the ecclesiastical tribunal at St Stephen’s Chapel four months later, for the purpose of sentencing. Archbishop Chichele of Canterbury begged illness from this event, and therefore it was Adam Moleyns, clerk to the royal council, who read the articles of sorcery, necromancy, and treason to her. Cobham again vociferously denied the charges but admitted to using potions to conceive a child with Humphrey. Several days before issuing a sentence, the ecclesiastical panel forcibly divorced Cobham from her husband. What due process was used to work the divorce is not recorded. Certainly, it was not initiated by Humphrey, and under canon law there were no grounds for divorce if one of the spouses fell into heresy.[10] Cobham’s sentencing hearing came a few days later, and she was given the punishment of walking penitent at three public market days. Thenceforth, she never left the king’s strict custody and is believed to have died at Beaumaris, Wales, in 1452, five years after Humphrey.[11]

The Penance of Eleanor Cobham, by Edwin Austin Abbey (1900)

While not a perfect analogue, the Cobham case is instructive as to how a hypothetical ecclesiastical tribunal would have litigated the precontract issue in 1483. It would have had an initial hearing when the charge was announced, then it would have received witness testimony, and then it would have had announced its decision after review of the evidence. Elizabeth Woodville’s presence would not have been required but she could have had a proctor there to represent her interests.[12] Of course, there would have been no jury, and none of the safeguards that juries ostensibly brought to secular litigation. Those sitting on the tribunal would not have heard live testimony nor observed the demeanor of those testifying; they would have relied on recorded depositions. There would have been no requirement for a reasoned opinion describing the rationale for the decision. And there would have been no sentencing hearings, since the only role for this tribunal would have been to answer one question about the precontract’s existence. The matter would then be returned to the secular courts, including Parliament, for further consideration.

What type of evidence would have been received?

One was required to produce documentary evidence and/or witness testimony to substantiate a claim in the church courts. Documentary evidence was almost unheard of in marriage cases, and even it if had been produced, forgery was so common that it was often looked at as being less weighty than oral testimony.[13] If resting solely on witness testimony, then the case could be proven with only two people who were able to testify from direct observation or other reliable information. The ‘two-witness rule’ was formulated in pre-Christian classical Rome as full proof (‘probatio plena’) and was absorbed into church doctrine based on certain passages in the Bible. Hearsay was not excluded. In a 1443 case from the Rochester diocese, for example, the church court allowed the testimony of John North who said that William Gore told him of seeing a marriage contracted between Alice Sanders and John Resoun.[14] Proof of long cohabitation and children being born to a couple were not relevant except to prove sexual intercourse. Beyond that, what sentimental force it had on the judge is hard to say, certainly less than it would today. The validity of a marriage depended on the existence of a marriage contract, not on the birth of children. What was more relevant to church courts were the relative social statuses of the parties involved, as can be seen in a 1419 case where a woman lost her precontract case because the putative husband introduced witnesses to show that he was of a far superior social station.[15]

Since marriage cases often turned exclusively on the testimony of two people, we find paradoxes and difficulties, and cases involving collusion and fraud. Helmholz recounts a case from York where Alice Palmer had married Geoffrey Brown and lived with him for four years. The union was not a happy one as Geoffrey physically abused Alice. As a result, Alice and her father found another young man, Ralph Fuler, and gave him gifts (i.e. bribes) so that he would say that he had contracted marriage with the said Alice before any contract and solemnization of marriage had occurred between Alice and Geoffrey. ‘This stratagem worked. Alice and Geoffrey were divorced. The whole matter came to light only some years later, after Geoffrey had in fact married another girl. Alice then sued to annul the previous judgment and get him back.’[16] Helmholz also recounts coming across a few isolated cases where an affirmative judgment was based on the testimony of a lone witness rather than the two required.[17]

For this reason, John Fortescue wrote about the inanity and corruption of the ‘two-witness rule’, saying that it was clearly inferior to the English common law system which required a jury of 12 good men to attest to the truth of the facts presented by the prosecution. To prove his point, Fortescue used the example of someone entering into a valid clandestine marriage, walking away from that, and then marrying someone else in a public ceremony to which two witnesses could testify in a court, and none to the clandestine marriage. The Roman law requiring two witnesses in this situation, according to Fortescue, would condemn the person to live in perpetual adultery with the second wife.[18] But two witnesses were all that was required in the ecclesiastical courts, and that is all that would have been required in 1483 to prove the precontract, and thus the princes’ illegitimacy.

Medieval court in session

If Phillipe de Commynes was accurate, then we already know the identity of one witness: Robert Stillington, bishop of Bath and Wells, and former chancellor to Edward IV. And this is significant because the ‘two-witness rule’ had numerous exceptions. William Durantis, the medieval procedural encyclopedist, managed to elucidate thirty of them. Most were created for situations in which it would be expected and natural for only one witness to observe an event (a father, for instance, testifying that his son had been coerced into becoming a monk was sufficient to prove that fact). Other exceptions rested on the quality of the witness. The testimony or word of the Pope or other high clergyman, for instance, could alone prove a fact in the church courts.[19] In a strict sense, the testimony of a sitting bishop and former Chancellor, coming from a high clergyman about a clandestine marriage that he personally observed, could have fallen into one of these exceptions to the rule and it alone might have been deemed full proof of the precontract.

Aside from the requirement of two witnesses and its exceptions, the church courts applied a somewhat mechanical system for sorting out qualified from unqualified, and believable from unbelievable, testimony. The parties themselves could not testify as they were deemed partial to their side of the case. For the same reason, the parties’ servants, friends, and relatives, were deemed unqualified to testify. Heretics and believers who were in the state of mortal sin could not testify at all. Rank in the nobility or clergy merited a witness superior credit, rich man prevailed over poor, Christian over Jew.[20] Had Bishop Stillington, or another high clergyman, testified in front of an ecclesiastical tribunal in 1483, then his testimony would have been accorded the highest evidentiary weight possible under the rubrics set out by canon law.

But what about the duke of Buckingham and the preachers who were making public statements in 1483 about the princes’ illegitimacy? Could they have testified in a canon court? The answer seems to be in the affirmative. As shown above, the fact that none were present at the time of the precontract would not necessarily bar their testimony since there was no strict rule against hearsay. The problem rests in what they were saying, which suggested different grounds for the princes’ illegitimacy (the duke saying that Edward IV was precontracted to a foreign princess, and the preachers saying it was because Edward IV himself was a bastard). Under canon law, full proof required two witnesses providing the same basic facts, not two different scenarios for invalidating a marriage.

There is also Mancini’s insinuation that the preachers were ‘corrupt’ in some manner, and even a suggestion by Commynes that Stillington had some sort of personal baggage when he was briefly sent to the Tower in 1478. Canon law permitted any witness, even a clergyman, to be impugned and ignored if they were shown to be of bad character. That required proof, too, not mere suspicion, and there was no mechanism to cross-examine witnesses directly. One had to produce evidence, usually in the form of another witness, to show that someone was unqualified. According to Professor Charles Donahue, English church courts were often more lax about this than they should have been. He found several cases in which the court proceeded to sentencing without regard to the fact that the witnesses on the winning side were objectionable. In a precontract case, Cecilia Wright c. John Birkys, Cecilia successfully petitioned for a divorce of John from his current wife, Joanna, on the ground that John had previously promised to marry Cecilia and had had intercourse with her. Cecilia produced only two witnesses, one of servile condition, the other Cecilia’s sister and the wife of the other witness. ‘Probably neither witness was admissible under the academic law. Yet despite uncontradicted testimony as to the status and the witness’s admission of the relationship, Cecilia prevailed in two courts.’[21]

Such cases suggested to Professor Donahue that in English church court practice, there was no automatic bar to the consideration of anyone’s testimony. Indeed, he concluded ‘there is no case of which I am aware in which a party lost because some or all of the witnesses necessary to make up his case proved to be incapable of testifying under canon law’.[22] It has led modern historians to say that the church courts were often deciding marriage cases based on ‘evidence that was seldom sufficiently verified’ and that ‘some judges appear to have bent the law to fit their normal, and sensible, prejudices’.[23]

How conclusive would the decision have been?

Once the ecclesiastical tribunal had decided the issue of the precontract, the matter would be returned to the secular courts to determine whether the children could inherit under English law. A certificate of legitimacy or bastardy coming from the Church could not be challenged in any subsequent lawsuit, even if it involved different parties, facts, or issues.[24] This was the general rule, although Helmholz found cases where English secular judges disobeyed the church court’s decision when it would have worked an inequity or a violation of English law. They were particularly sensitive to church intrusion into matters involving inheritance. In a case from 1337, for example, it was pleaded that the plaintiff was a bastard by reason of birth before his parents’ marriage. The plaintiff countered by showing the record of a bishop’s certificate from a previous decision testifying to his legitimacy. The court, however, refused to accept it as conclusive. As Judge Shareshull said, ‘I cannot have this answer because with it a man would gain inheritance against the law of the land.’[25] Shareshull would later become Edward III’s chief justice in 1350.

St-Mary-le-Bow Church, London, designed by Christopher Wren.

Less certain is whether any appeal could have been made to the Pope. Since the matter ultimately concerned inheritance law and feudal succession to the English throne, it seems unlikely. Certainly, Elizabeth Woodville and her allies did not take up any appeal to the Roman Curia after her sons by Edward IV were declared illegitimate by the three estates. Such an effort, in any case, might have arguably violated the Statutes of Praeminure enacted during the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. They forbade Englishmen and women to pursue in Rome or in the ecclesiastical courts any matter that belonged properly before the king’s courts, including ‘any other things whatsoever which touch the king, against him, his crown and his regality, or his realm’. There were strict penalties for doing so.[26]

Conclusion

The decision not to refer the issue of the princes’ alleged bastardy to a church court will always remain one of the criticisms of how Richard III came to the throne. As shown above, there were serious procedural dilemmas, such as how to properly constitute an authoritative ecclesiastical tribunal and how such a tribunal would have managed the hearing of a politically divisive claim. Even more difficult to predict is whether the church tribunal would have accepted a lowered burden of proof of just one eyewitness’s testimony to the precontract or would have sought out additional witnesses. In the final analysis, these matters of procedure do not dictate the outcome. As long as there was credible proof of the precontract, strict church law would have bastardized the offspring of the bigamous parents. English secular law did not soften this result, and indeed, militated against such children from inheriting their father’s estate. The ultimate question is whether the English public would have found an ecclesiastical tribunal to satisfy their notions of due process, or whether they would have seen it merely as a handmaiden to a political coup d’etat. It seems safe to say that we’d still be debating the merits and propriety of Richard III’s accession to the crown regardless of the juridical mechanisms employed, even if those mechanisms followed the precise letter of canon law.

Related Posts

“Debunking The Myths – How Easy Is It To Fake A Precontract?”

Notes

[1] R. H. Helmholz, “Bastardy Litigation in Medieval England,” American Journal of Legal History, Vol. XIII (1969), pp. 360-383 and R. H. Helmholz, “The Sons of Edward IV: A Canonical Assessment of the Claim that they were Illegitimate,” Richard III Loyalty, Lordship and Law, P.W. Hammond (ed.) (1986).

[2] Nicholas Pronay & John Cox (eds.), The Crowland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486 (Allan Sutton, London, 1986), pp. 158-161.

[3] C. A. J. Armstrong (trans.), The Usurpation of Richard the Third by Dominicus Mancinus (Oxford Univ. Press, 1936), pp. 116-121.

[4] ‘In the end, with the assistance of the bishop of Bath, who had previously been King Edward’s Chancellor before being dismissed and imprisoned (although he still received his money), on his release the duke carried out the deed which you shall hear described in a moment. This bishop revealed to the duke of Gloucester that King Edward, being very enamoured of a certain English lady, promised to marry her, provided that he could sleep with her first, and she consented. The bishop said that he had married them when only he and they were present. He was a courtier so he did not disclose this fact but helped to keep the lady quiet and things remained like this for a while. Later King Edward fell in love again and married the daughter of an English knight, Lord Rivers. She was a widow with two sons.’ Michael Jones (trans. & ed.), Philippe de Commynes “Memoirs”, 1461-83 (Penguin Books, 1972), pp. 353-54.

[5] Rosemary Horrox (ed.), The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England 1275-1504, Vol. XV Richard III 1484-85 (Boydell, London, 2005), pp. 13-18.

[6] There was no preference by canon law courts favoring the ‘settled’ or ‘long-standing’ marriage over the mere contract by words. R. H. Helmholz, Marriage Litigation in Medieval England (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1974), pp. 57-59, 62-64.

[7] Helmholz, Bastardy Litigation, pp. 381-383. The Statute of Merton was passed during Henry III’s reign in 1235, and provided in part, that ‘He is a bastard that is born before the marriage of his parents’. The parents’ subsequent marriage did not alter the status of bastardy.

[8] Ralph A. Griffiths, “The Trial of Eleanor Cobham: An Episode in the Fall of Duke Humphrey of Gloucester”, King and Country: England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century (Hambledon, London, 1991), pp. 233-252.

[9] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 124-140, 113-115.

[10] Pierre Payer (trans.), Raymond of Penyafort’s Summa on Marriage (Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2005), pp. 53, 80-81. In Title X, Dissimilar Religion, Penyafort states that when believers contract marriage between themselves and afterwards one falls into heresy or the error of unbelief, the one who is abandoned cannot remarry.

[11] Griffiths, Eleanor Cobham’s trial.

[12]Brian Woodcock, Medieval Ecclesiastical Courts in the Diocese of Canterbury (London, 1952), pp. 83-85.

[13]James A. Brundage, Medieval Canon Law (Longmans, London, 1995), pp. 132-133.

[14] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 131-132.

[15] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 132-133.

[16] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, p. 162.

[17] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 228-232.

[18] Shelly Lockwood (ed.), Sir John Fortescue: On the Laws and Governance of England (Cambridge Univ Press, 1997).

[19] R. H. Helmholz, “The Trial of Thomas More and the Law of Nature”, http://www.thomasmorestudies.org/ tmstudies/Helmholz2008.pdf [7/3/08], pp 9-10, FN 31.

[20] Mauro Cappelletti & Joseph M. Perillo, Civil Procedure in Italy (Columbia Univ., 1965), pp. 34-35, footnote 139 cites the Decretals of Gregory IX, Liber Extra, title XX de testibus et attestationabus, cap. XXVIII.

[21]Charles Donahue, Jr., “Proof by Witnesses in the Church Courts of Medieval England: An Imperfect Reception of the Learned Law”, in Morris S. Arnold, Thomas A. Green, Sally Scully, and Stephen White, ed., On the Laws and Customs of England: Essays in Honor of Samuel E. Thorne (North Carolina Univ. Press, 1981), pp. 127–154 and p. 147, footnote 89, citing case from York, Borthwick Institute, CP.E. 103, 1367-69.

[22] Donahue, Proof by Witnesses, p. 147. It should be noted that Donahue’s research focused on the 13th and 14th centuries, but Helmholz’s research did not reveal any different trends in the 15th century.

[23] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 61-62, citing Lacy, Marriage in Church & State, and p. 66.

[24] Helmholz, Bastardy Litigation, p. 373.

[25] Helmholz, Bastardy Litigation, p. 374.

[26] 27 Edw.III st. 1, c. 1, 38 Edw. III st. 2, cc. 1-4, 16 Rich.II c. 5. Richard Burn, Ecclesiastical Law, Vol. II (9th ed., 1842) pp. 37-39.