Richard III remains one of the most controversial kings of England because of the manner in which he came to the throne: not by battle or conquest, but by a legal claim that Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid, rendering their children ineligible to stand in the line of succession. The grounds for the legal claim were enumerated in a petition brought forth to the Three Estates in June 1483, and were later entered into the January 1484 rolls of Parliament under the Act commonly referred to as Titulus Regius (title of the king).

On close inspection, Titulus Regius asserted four reasons justifying the invalidation of Edward IV’s marriage to Woodville:

First, he did so without consulting his own royal council, government, or the peers of the realm (‘And here also we consider how that the said pretensed marriage betwixt the above-named King Edward and Elizabeth Grey was made of great presumption, without the knowing and assent of the lords of this land’).

Second, it was achieved through witchcraft (‘And also by sorcery and witchcraft committed by the said Elizabeth and her mother Jaquette, Duchess of Bedford, as the common opinion of the people and the public voice and fame is through all this land … [which] shall be proved sufficiently in time and place convenient’).

Third, it was improper under church law (‘And here also we consider how that the said pretensed marriage was made prively [sic] and secretly, without edition of banns, in a private chamber, a profane place, and not openly in the face of the Church, after the law of God’s Church’).

Finally, Edward IV had been previously married to Eleanor Talbot (‘And how also that at the time of contract of the same pretensed marriage, and before and long time after, the said King Edward was and stood married and trothplight to one Dame Eleanor Butler [née Talbot], daughter of the old earl of Shrewsbury, with whom the same King Edward had made a precontract of matrimony, long time before he made the said pretensed marriage with the said Elizabeth Grey in manner and form abovesaid’).

There is no controversy surrounding the first and third legal grounds asserted in Titulus Regius. They stated known and uncontested facts. Edward IV’s wedding to Woodville was conducted without any input from the king’s ministers, it was ‘clandestine’ in the eyes of the medieval Church, and it deviated from centuries of English royal practice. A king’s marriage was a matter of great importance for the realm as it provided an opportunity for England to form a military and economic alliance with a foreign power, and it involved carefully managed negotiations between high-level diplomats over things like the future queen-consort’s dowry and how she would be financially supported. The announcement of the Woodville marriage in 1464 – presented months later as a fait accompli and denying the public the spectacle of a grand wedding – was not greeted with universal joy and acceptance. It alienated many of the king’s most important supporters, the most notable being Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, aka the ‘Kingmaker’. These facts are accepted by virtually all historians.

The most controversial aspects of Titulus Regius are the other two grounds – witchcraft and precontract. This essay will not get into the witchcraft claim, but will focus instead on the alleged precontract between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot. In courts throughout fifteenth-century Continental Europe, the existence of a previous marriage contract would not have been referred to an ecclesiastical court, but would have been determined by their own civil or quasi-secular courts. Yet England, despite rejecting many elements of medieval church doctrine on marriage irregularities and children’s illegitimacy, retained a feature of ancient Roman Christian custom. Any claims of an irregular marriage were to be referred to the English ecclesiastical courts and adjudicated by their custom and legal procedure.

The casual reader of history is probably familiar with the evidence produced in 1483. It was given by Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, who reportedly came forth and gave eyewitness testimony that he had personally witnessed the exchange of marriage vows between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot. This occurred before the king took Elizabeth Woodville as his consort.

No one has addressed whether Stillington’s testimony was sufficient to satisfy the burden of proof under church legal procedure. Was it enough to stand up in court? But, first, did Stillington really give this testimony?

There was Evidence of the Precontract

The primary source material concerning Stillington’s testimony comes from Philippe de Commynes (1447-1511), the relevant parts of whose Memoirs of the Reign of Louis XI were written sometime between 1489-1491. Commynes wrote this work for Angelo Cato, bishop of Vienne, the same man who commissioned Domenico Mancini to travel to England during the fateful Spring of 1483. The moralizing tone of the Memoirs suggests a wide audience, in the medieval ‘Mirror for Princes’ tradition. Book 6 of the Memoirs contains the following narrative about events in England in 1483, beginning with Edward IV’s sudden death:

‘King Edward left a wife and two fine sons; one called the prince of Wales, the other the duke of York. The duke of Gloucester, brother of the late King Edward, took control of the government for his nephew, the prince of Wales, who was about ten years old, and did homage to him as king. He brought him to London, pretending that he was going to have him crowned, but really to get the other son out of sanctuary in London where he was with his mother, who was somewhat suspicious. In the end, with the assistance of [Robert Stillington] the bishop of Bath, who had previously been King Edward’s Chancellor before being dismissed and imprisoned (although he still received his money), on his release the duke carried out the deed which you shall hear described in a moment. This bishop revealed to the duke of Gloucester that King Edward, being very enamoured of a certain English lady, promised to marry her, provided that he could sleep with her first, and she consented. The bishop said that he had married them when only he and they were present. He was a courtier so he did not disclose this fact but helped to keep the lady quiet and things remained like this for a while. Later King Edward fell in love again and married the daughter of an English knight, Lord Rivers. She was a widow with two sons.’[1]

Later, Commynes circles back to these events, adding the detail that Edward IV died of ‘apoplexy’ (cerebral hemorrhage) after learning he’d been duped by Louis XI in past diplomatic exchanges, and giving the following narrative:

‘For after the death of King Edward, the duke of Gloucester had done homage to his nephew as his king and sovereign lord. Then immediately he had committed this murder [sic] and, in the full English Parliament, he had the two daughters of Edward degraded and declared illegitimate on the grounds furnished by the bishop of Bath in England. The bishop had previously enjoyed great credit with King Edward, who had then dismissed and imprisoned him before ransoming him for a sum of money. The bishop said that King Edward had promised to marry an English lady (whom he named) because he was in love with her, in order to get his own way with her, and that he had made this promise in the bishop’s presence. And having done so he slept with her; and he made the promise only to deceive her. Nevertheless such games are very dangerous, as the consequences show. I have known many courtiers who, if such good fortune had befallen them, would not have lost it for want of promises. This wicked bishop kept thoughts of revenge in his heart for, perhaps, twenty years. But it turned out unfortunately for him, for he had a son whom he loved a great deal whom King Richard wanted to endow with wide estates and to marry to one of those two daughters who had been degraded – the one who is the present queen of England and has beautiful children. This son was serving in a warship by command of his master, King Richard. He was captured on the coast of Normandy….’[2]

While there are factual errors in Commynes’ Memoirs, for instance Stillington never had a son as described above, this essay will assume that the part about the bishop giving evidence in 1483 is true because it is corroborated elsewhere. As reported in the September 2018 issue of the Ricardian Bulletin, he was identified in a 1486 Year Book, when the lords and justices wished to question him because ‘the Bishop of B made the bill’. In 1533 and 1534, Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador to England, wrote to Emperor Charles V that he had been told by ‘many respectable people’ in England that Henry VIII ‘only claims [the crown] by his mother, who was declared by sentence of the Bishop of Bath a bastard, because Edward [IV] had espoused another wife before the mother of Elizabeth of York’.[3]

Professor Richard Helmholz, a medieval canon law expert at the University of Chicago School of Law, has already demonstrated that Titulus Regius stated a valid and recognized basis to bastardize Edward IV’s children under medieval canon law. When two adults like Edward IV and Talbot voluntarily exchanged promises to marry the other, and then had sexual intercourse, they formed an enforceable and binding contract. Woodville could not claim she was an innocent victim of deception, because her own marriage to the king violated church law requirements. There was no rule preventing such a claim from being raised after the deaths of the putative spouses; indeed, this was frequently done in inheritance disputes in England. In short, if what Stillington said were true, then Edward IV had committed bigamy and had polluted Woodville from ever becoming his legal wife. In assessing Titulus Regius, Helmholz conceded that there was a singular, procedural defect in jurisdiction: it hadn’t been referred to a church court to determine the truth of the previous marriage contract.[4]

So how would Stillington’s testimony about the Talbot marriage have fared, if it had come before an ecclesiastical tribunal for adjudication in 1483 or 1484? Would the court have taken it at face value and received it into evidence, or would there have been some additional process to ensure it was truthful? Would it have been enough to prove the case, and shift the burden of proof to Woodville and her sons to show they weren’t bastards, or was other proof of the Talbot marriage required? In order to answer these questions, it is necessary to review briefly the ecclesiastical court rules on witness testimony.

Qualified Witnesses in Marriage Litigation

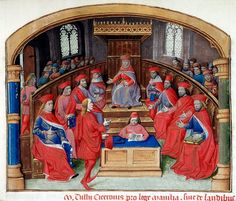

The great medieval canonist, Raymond of Penyafort, set out in his Summa on Marriage that lawsuits to annul a marriage could not be maintained unless they were initiated by qualified accusers and supported with qualified witnesses. In actions alleging a perpetual impediment such as described in Titulus Regius, the spouses themselves or any of their blood relatives could bring a claim; if no blood relatives were alive, a total stranger to the family could initiate it.[5] These were all qualified to bear witness against the marriage, unless they lacked legal standing because they were heretics, perjurers, felons, excommunicated, of servile (villein) station, or juveniles.[6]

But there was an interesting wrinkle in this broad rule, which Penyafort took pains to address. If a person had been able to raise the objection to the marriage at the time it was made, they would not be heard to testify later against it. This would seem to preclude Stillington from testifying, since he was aware of the Talbot marriage yet did not raise any objection when Edward IV entered into his union with Woodville. Penyafort expounds on this situation in the following way:

‘If, indeed, after a marriage is contracted an accuser appears, since he did not speak out in public when the bans [sic] were published by custom in the churches, we can well ask whether his accusation should be admitted. On this we are led to make the following distinction: if at the time of the aforesaid announcement he who attacks the marriage was outside the diocese, or the announcement could not reach him for some other reason, so that, for example, laboring under a fever from serious illness his sanity deserted him, or he was of such tender years … or was impeded by some other lawful cause, his accusation ought to be heard.’[7]

It is historical fact that the Woodville marriage was not announced by banns or official government proclamation. It had been conducted clandestinely in a private chapel or house, and was kept secret from Edward IV’s own government for several months. Without knowing exactly where and when it happened, no one can say whether Stillington was in the same diocese, or could have remotely raised an objection. It seems extremely unlikely. This interesting wrinkle, in other words, would not have applied to the facts of the case, and would not have supported an objection to Stillington’s testimony.

Trustworthy Witnesses – Fidedignus and Fidedigni

When a witness gave testimony, their character and manner of testifying would be measured against the theological concept of a ‘trustworthy man’. The Ordinary Gloss of Pope Gregory IX’s Decretals described trustworthy men as those of good reputation, held in high regard, and older in age, citing several texts referring to the wisdom of age.[8] This can also be seen in the canonical use of the terms fidedignus or fidedigni (literally, ‘faith-worthy man’ or ‘faith-worthy men’) in describing the type of people who were summoned to testify in church inquisitions, visitations, and in settling the estates of the deceased.

Professor Ian Forrest of Oxford’s Oriel College surveyed the evolution of the trustworthy man concept, including hundreds of diocesan court papers from medieval England. He concluded that the following characteristics enhanced a witness’s credibility as a fidedignus in the eyes of the medieval church:[9]

- High status, power, and position

- Consistency in their testimony

- Proximity to events in question

- Having better knowledge than others (e.g., being an eyewitness)

- Manner of speech

- Objectivity and lack of bias towards or against one party

- Not reluctant to give information

- Expertise in any technical, legal, or fact issue at hand

- Current secular or ecclesiastical officeholder in good standing

- Landholder who is in good stead with paying their taxes

- Male gender

While Professor Forrest was primarily looking at the process of church inquests and visitations, what he has described is equally applicable – and is indeed a common theme – in how witnesses were assessed in run-of-the-mill medieval marriage disputes. What little we know about Stillington indicates that he received a Doctorate of Civil Law from Oxford before 1443, and thus was a trained canonist, having demonstrated proficiency in Roman civil law and mastery of canon law.[10] He rose quickly in the service of Bishop Beckington of Bath and Wells, received diplomatic assignments from Henry VI, and had been recommended to his benefices by a handful of English bishops. He was Edward IV’s Keeper of the Privy Seal when he personally witnessed the vows exchanged between Talbot and the king. At the time, he was an Archdeacon of Taunton but was later promoted in Edward IV’s government, serving as his Chancellor from 1467 to 1473, and becoming the Bishop of Bath and Wells in 1466, a bishopric he held continuously until his death. As far as we know, he had no personal animosity against Woodville or her children, and had nothing to gain by testifying in 1483.[11]

We do know that in 1478, around the time of George of Clarence’s treason trial and execution, Stillington had been arrested and briefly held in custody by Edward IV. For what, is still a matter of intense speculation. No charges were brought against him. He was released after paying a fine, pardoned without loss of income or status, and would be employed as a royal ambassador in 1479. There is some suggestion that his health was failing, or that his advancing age (he was born circa 1410) kept him from further government service. There is also some suggestion, by Commynes, that he was resentful of the treatment he had received in 1478 at the hands of Edward IV, and possibly even expected to receive some form of reward for the evidence he gave in 1483. These would all be areas for a church tribunal to interrogate.

Probatio Plena – the Two Witness Rule

While Stillington’s testimony would have satisfied the elements of proof needed to establish the Talbot marriage (exchange of vows, consummation), one last hurdle existed. Following Roman civil law, a case relying solely on oral testimony had to be proven with at least two witnesses whose accounts were consistent with each other. The ‘two-witness rule’ had its origins in pre-Christian Rome as full proof (‘probatio plena’) and was absorbed into church doctrine based on certain passages in the Bible. Unsurprisingly, church fathers encountered problems with the rule’s functionality in litigation involving clandestine marriages and illicit sexual behavior. There was nothing to prevent a scallywag from seducing his paramour with a private, unwitnessed exchange of words creating a marital contract, then abandoning her for a subsequent partner in a public ceremony witnessed by dozens. Without two witnesses to testify to the first marriage, the courts could not enforce it, leaving the couple to the second marriage condemned to live in a perpetual state of bigamy.

‘When a witness in a 1291 marriage suit claimed to have been an eyewitness to a man and a woman having sex (hoc vidit oculate fide), he was making a claim that was meant to boost the significance of his testimony. But on his own he could not meet the canonical standard of proof, which demanded two witnesses who had seen or heard the events at issue. In cases hinging on sexual activity this was an understandably rare occurrence. For some in the church facing the huge challenge of separating the clergy from their wives and concubines in the wake of twelfth-century reform, the standard of proof was unacceptably high. In the succeeding generations canon lawyers began to assert new doctrines of proof that made it easier for the authorities to convict offenders.’[12]

Exceptions to the two-witness rule were carved out. In his highly influential encyclopedia of procedural canon law, William Durandis (1231-1296) identified more than two dozen scenarios where one witness would suffice as probatio plena. The word of the Pope or other high clergyman, of course, could alone prove a fact.[13] A father’s testimony could alone prove that his son had been coerced into becoming a monk. ‘Half-full’ proof such as that provided by one unimpeachable witness could be converted to full proof by other indicia, such as circumstantial evidence or solid evidence of publica fama.[14] Publica fama or public fame was the report of many people, what Ian Forrest described as the ‘suspicion amongst good and serious men of the neighbourhood, and it was thought sufficient to force a suspect to answer before a judge’.[15] In support of this notion, Helmholz quotes from one of Pope Gregory IX’s Decretals which went so far as to say that ‘if the crime is so public that it may rightly be called notorious, in that case neither witness nor accuser is necessary’. Titulus Regius implicitly alludes to this notion when it says the Woodville marriage was invalid, ‘as the common opinion of the people and the public voice and fame is throughout all this land.’[16]

Conclusions

Based on this reading of the canon law, it seems evident that Stillington would have been allowed to give evidence about his personal knowledge of the Talbot marriage, even though he did not object after hearing about the king’s clandestine marriage to Woodville. His testimony would have presented compelling evidence, since he was an eyewitness to the exchange of promises and was aware of their subsequent sexual consummation. As a bishop and Oxford-trained canonist, he would have been granted the standing of a fidedignus, but his testimony could have been impeached if it were shown, as implied by Commynes, that he harbored a personal grudge against Edward IV for his arrest in 1478, or that he had done something bringing his character and truthfulness into question. But as the historical record currently stands, there is no factual evidence to support impeachment.

The more nagging question is whether Stillington’s testimony could have been enough to prove the Talbot contract, or whether it needed to be supported with another witness or evidence of public notoriety. In their exhaustive surveys of medieval church litigation, Professors Richard Helmholz, Charles Donahue, and Ian Forrest discovered many cases when an English church court ruled that a precontract had been proven with only one witness to it. But none of those cases involved members of the royal blood, or dictated the succession to the English crown.

It would be most interesting to compare how other medieval aristocrats in Western Europe marshaled evidence to dissolve or challenge their marriages. One suspects that some end-run around canon law might have been tolerated if the political aim was popular, or if a full-blown trial of the claim would have mired a government in protracted and divisive litigation. This was Professor Helmholz’s conclusion too. Eleanor of Aquitaine and King John both managed to annul their first marriages by claiming somewhat disingenuously that an impediment of consanguinity existed with their spouses, a ‘discovery’ they made, respectively, 15 and 10 years after solemnization of their original marriage vows. Henry VIII tried to annul his marriages to Anne Boleyn, Anne of Cleves, and Catherine Howard based on the existence of previous marriage contracts, but he only succeeded in proving one of them because the woman in question (Cleves) confessed to it.[17]

Nevertheless, Richard III did have a reputation for being a keen observer of legal procedure, and he must have been aware of the long-standing church doctrine on probatio plena. The words of Titulus Regius itself seem to admit this defect with Stillington’s testimony when it says the invalidity of Edward IV’s marriage to Woodville was a matter of common opinion. Presumably, the author of that petition, and probably Richard III himself, would have been prepared to substantiate that allegation if required by church authorities.

Author’s Note: I would like to thank my fellow Loon for pointing out Henry VIII’s trials and travails in annulling his marriages, and referring me to H.A. Kelly’s article and text cited in the Endnotes. She wrote a very thought-provoking comparison between Henry VIII’s and Richard III’s precontract claims, which can be found at https://ricardianloons.wordpress.com/2016/03/06/debunking-the-myths-how-easy-is-it-to-fake-a-precontract/

(An earlier version of this essay was published courtesy of the Ricardian Bulletin, June 2021, copyright holders Susan Troxell and the Richard III Society, CLG)

[1] M. Jones (trans. & ed.), Philippe de Commynes Memoirs, The Reign of Louis XI 1461-83, Penguin Books, 1972, pp. 353-54.

[2] Ibid, pp. 396-397.

[3] D. Johnson, P. Langley, S. Pendlington, ‘More than Just a Canard: The Evidence for the Precontract,’ Ricardian Bulletin, September 2018, pp. 51-52.

[4] R.H. Helmholz, ‘Bastardy Litigation in Medieval England,’ American Journal of Legal History, Vol. XIII (1969), pp. 360-383. R.H. Helmholz, ‘The Sons of Edward IV: A Canonical Assessment of the Claim that they were Illegitimate,’ in Richard III Loyalty, Lordship and Law, P.W. Hammond (ed.), 1986, pp. 106-120.

[5] P. Payer (trans.), Raymond of Penyafort, Summa on Marriage, Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2005, Title XX, p 75-76.

[6] R. H. Helmholz, Marriage Litigation in Medieval England, Cambridge Uni Press, 1974, pp. 154-164.

[7] Summa on Marriage, Title XX, para. 2, p. 76.

[8] Ian Forrest, Trustworthy Men: How Inequality and Faith Made the Medieval Church, Princeton University Press, 2018, pp. 108-109.

[9] Trustworthy Men, pp. 91-119.

[10] Kelly, ‘The Case Against Edward IV’s Marriage and Offspring’, The Ricardian, September 1998, p. 326-335.

[11] Bryan Dunleavy, ‘Will the Real Bishop Stillington Please Stand Up?’, Ricardian Bulletin, September 2020, pp. 54-57. Michael Hicks, ‘Robert Stillington d. 1491’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[12] Trustworthy Men, pp. 252-253, citing Norma Adams and Charles Donahue, Jr. (eds.), Select Cases from the Ecclesiastical Courts of the Province of Canterbury c. 1200-1301, Selden Society, 1981, p. 357.

[13] R. H. Helmholz, ‘The Trial of Thomas More and the Law of Nature,’ http://www.thomasmorestudies.org/tmstudies/Helmholz2008.pdf (7/3/08) pp 9-10, footnote 31 (accessed 12/1/2019). Professor Charles Donahue at Harvard University describes the case of Taillor and Smerles versus Lovechild and Taillor, from 1380, in which a woman proved her marriage using the testimony of only one witness. She prevailed even though her estranged husband called 4 witnesses to testify that she was actually married to someone else. It is important to note that the prevailing woman used the testimony of a chaplain who had been present when the parties exchanged words of a de presenti marriage contract. Clearly, to the court, the testimony of a single churchman was better than 4 non-clerics. Charles Donahue, Jr., Law, Marriage, and Society in the Later Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 274-5.

[14] Law, Marriage, and Society, p 164.

[15] Trustworthy Men, pp. 251-259, 254.

[16] Helmholz, The Sons of Edward IV: A Canonical Assessment, pp. 116-117.

[17] H.A. Kelly, The Matrimonial Trials of Henry VIII, Wipf and Stock; Reprint edition 2004, pp. 252-258 discusses the church court procedure used to try to annul the marriage to Anne Boleyn.