Most historians now accept that, while the white rose of York was a heraldic badge used by the house of York during the Wars of the Roses, the origins of the red rose of Lancaster can only be traced back to Henry VII.1 After his accession to the throne in 1485 and marriage to Elizabeth of York he effectively invented it when he created the bi-coloured red and white Tudor rose, which symbolised the union of the houses of Lancaster and York. But what about the origins of the white rose of York?

The Welsh Marches – Yorkist Heartland

It is hard to over estimate the influence their Mortimer ancestry had on the Yorkists and their claim to the English throne. The Mortimers were descended from Lionel, duke of Clarence, the third son of King Edward III, whereas the Lancastrian kings of England were descended from his fourth son, John duke of Lancaster. The Mortimer claim, albeit through a female line, was therefore more senior and the Mortimers had long been viewed with suspicion because of this. Upon the death of Edmund Mortimer, fifth earl of March and the family’s last male descendant, both his title and claim to the throne passed to the son of his sister Anne – Richard, third Duke of York (who also had a claim through is paternal ancestors, albeit less senior). York also inherited most of his wealth and therefore the funding for his campaign to eventually press this claim from his Mortimer ancestors. The lands he received included the town of Ludlow in the Welsh marches and its castle, where he and his family spent time and his sons Edward and Edmund had their own separate household, just like Edward’s own son later did.

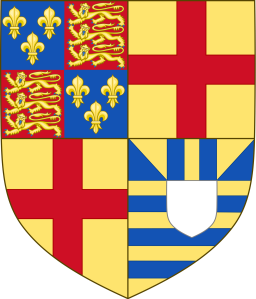

Even much of the symbolism we now think of as Yorkist originates from the Mortimers. They were not just the earls of March, but also earls of Ulster and both Richard, Duke of York and his eldest son Edward added Mortimer and Ulster to their coats of arms, as did Edward’s daughters.

Edward’s arms before he became Edward IV, combining the Mortimer arms, Ulster and the royal arms of England

Edward also adopted the white lion of the earls of March as heraldic badge alongside the sun in splendour, a sunburst allegedly inspired by his victory over the Lancastrians at the battle of Mortimer’s Cross in 1461. As the name suggests, this place is situated in the Welsh marches not far from Ludlow and the contemporary Davies Chronicle indeed records that just before the battle he had witnessed a natural phenomenon known as parhelion:

“the Monday before the day of battle, . . . about 10 at clock before noon, were seen 3 suns in the firmament shining full clear, where of the people had great marvel, and thereof were aghast. The noble Earl Edward them comforted and said, ‘be of good comfort and dread not; this is a good sign, for these three suns betoken the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, and therefore let us have good heart, and in the name of Almighty God go we against our enemies.’”2

However, the earliest source for the claim that “for the which cause, men imagined, that he gaue the sunne in his full brightnes for his cognisauce or badge” was the Tudor contemporary Edward Hall, whose chronicle wasn’t published until 1548, almost a hundred years after the battle. Moreover, as John Ashdown-Hill has noted:

“Edward, Earl of March (Edward IV) subsequently claimed to be the legitimate heir of his ancestor, King Edward III, and of Edward III’s grandson, King Richard II. Both of those earlier monarchs had also used forms of the sun as one of their royal badges in the fourteenth century.”3

Indeed, a list of heraldic badges used by Richard, duke of York allegedly dating from c. 1460 states that “The badges that he beareth by King Richard II is a white hart and the sun shining”, which implies that the house of York was already laying claim to a sunburst before the battle of Mortimer’s Cross which took place after the duke’s death.4 This would make sense given that the duke, when he submitted his claim to the throne to Parliament on 16 October 1460, specifically argued that after Henry IV, the first Lancastrian king, had deposed Richard II, the throne more properly belonged to Edmund Mortimer, who – as noted above – was descended from the third son of Edward III whereas Henry was only descended from his fourth son.5

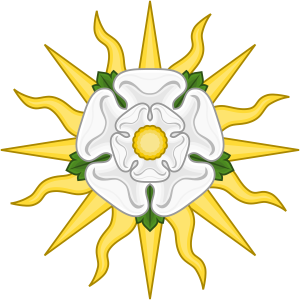

Whatever the inspiration for the sunburst in Yorkist heraldry, it is often seen combined with a white rose to form a rose-en-soleil. Edward, who was born in Rouen, France, where his father was stationed during the Hundred Years’ War, was referred to as “the Rose” or “the rose of Rouen” in Yorkist propaganda documents, such as this:

“Lette us walke in a newe wyne yerde, and lette us make us a gay gardon in the monythe of marche with thys fayre whyte ros and herbe, the Erle of Marche.”6

It is therefore not surprising that when Edward, now King Edward IV, incorporated Ludlow as a parliamentary borough in 1473, having set up the Council of Wales and the Marches in the previous year to act on behalf of his infant son and heir, Edward V, for whom he had established a household at Ludlow Castle, he granted the town a coat of arms that combined the white lion of the Earls of March with three white roses. But was this a case of merging existing Yorkist symbolism into Mortimer heraldry or the house of York seizing its Mortimer heritage and reinventing it as Yorkist?

The Mystery Of Misericord S15

The parish church of St Laurence in Ludlow, sometimes referred to as “Cathedral of the Marches” due to its size and beauty, dates back to at least Norman times, but it was substantially rebuilt in the 15th century after Richard, duke of York, had inherited the Mortimer titles and lands. Part of this building work, which started in 1433 and was completed around 1455, was to enlarge the chancel and add a new roof decorated with roof bosses heavy with Yorkist heraldry, such as Richard’s personal badge, the Falcon and the Fetterlock, and the white Hind at Rest of Richard II.

The chancel also received one of the finest collections of misericords to have survived England’s very own Cultural Revolution, King Henry VIII‘s Reformation. Medieval church services could be very long and misericords helped priests, monks or choristers to stand through them even if their seats were folded up by allowing them to lean against a ledge on the underside of the seat. Most of these ornately carved lean-tos were destroyed during the Reformation, in some cases used as firewood to melt the valuable lead out of stained glass windows, many of which were also lost at that time.

St Laurence’s is home to 28 misericords which appear to have been carved in at least two phases. The first is thought to date from about 1425 and produced 16 misericords while the remaining 12 were carved during the second phase, which followed the completion of the new chancel and roof. They were commissioned by the Guild of St Mary and St John, commonly known as Palmers Guild, a philanthropic confraternity of prominent citizens from Ludlow and the surrounding area. The Guild accounts for 1447 show that 120 planks of “waynscotbord” from Bristol had been acquired to make “new installations … in the high choir of the parish church …”.

The exact distribution of old versus new misericords is not certain as they were removed and reinstalled during the restoration of the church in the 19th century and no inventory was made to document their original position. It is however possible to date individual misericords based on the heraldry used in the carvings. For example, the fetterlock, a badge originally used by Edward Langley, first duke of York, appears on misericord N13 in combination with a falcon to form the personal badge of Richard, Duke of York and misericord S15 shows a rose within a fetterlock, clearly another reference to the house of York.

A further misericord, N15, has roses flanked by more roses. All three motifs also appear on roof bosses in the ceiling above, so must have been part of the second wave of carvings which followed the expansion of the chancel. Is this evidence for the white rose of York being imported into the Welsh Marches? Not so hasty.

Misericord S15 is actually reconstituted from fragments. The ledge with the carving of a rose within a fetterlock appears to have been grafted on to a plain seat and it is uncertain whether or not the twisted ring next to it is part of the original supporters as it is completely separate from the main carving.

The rose on S15 is similar in style to the supporters on misericord N15, so both misericords were probably carved in the same phase, and both have two layers of five petals each while the roses at the centre of N15 have one layer of five petals. However, the twisted ring is empty with no indication if it ever contained another image and, if so, what it was. In the ceiling above is a roof boss with a similar ring, divided into four segments and filled with foliage or flowers. Did the ring on S15 originally correspond to this roof boss? Or did it contain something else?

Leintwardine – The Missing Link?

In the village of Leintwardine, not far from the old Mortimer power base of Wigmore, stands the church of St Mary Magdalene. Its location is rural, its size modest and aesthetically it is unremarkable. Having been built in several phases from the 12th to the late 15th century, each new structure appears to have been grafted on to the earlier ones without much thought for symmetry. Nevertheless, it has received an unusual degree of attention from the powers that be. The Mortimers funded much of the building works and in 1328 Roger Mortimer, first Earl of March (1287 – 1330), made a grant for initially nine and later ten chantry priests to sing daily masses for the souls of King Edward III and Queen Philippa, Edward III’s mother Isabella (who infamously was rumoured to have been Roger’s lover and for a while ruled England with him), the bishop of Lincoln as well as his own family and ancestors. Despite having executed Roger for treason, Edward III himself made two pilgrimages to Leintwardine in 1353, gifting money on one visit and laying a cloth of gold before the statue of the Virgin Mary on the other.

Among the church’s treasures are the wooden choir stalls and misericords in its chancel. Their origin is uncertain. According to one theory, they were brought here from Wigmore Abbey at the dissolution of the monasteries, together with the carved stone fragments now fitted into the wall left and right of the altar. Wigmore Abbey, dedicated in 1179 by the Bishop of Hereford, but originally founded around 1140 at Shobdon by Oliver de Merlimond, a steward of Hugh Mortimer (c.1100 – 1181), was a place of great spiritual significance for the Mortimers and many of them, including several lords of March, were buried there. Tradition has it that every year on the feast of the nativity the abbot led a procession from Wigmore Abbey to St Mary Magdalene, so the church would seem like a natural new home for the choir stalls after the abbey was dissolved. Unfortunately, not much is left of the abbey apart from the abbot’s lodgings which are now incorporated into a private residence. The abbey church is almost completely destroyed, so doesn’t offer any clues.

According to another theory, the stalls were made for the Mortimer Chapel in St Mary Magdalene, which is thought to have been completed around 1353, sparking the visit from King Edward III. However, chantry chapels don’t normally contain choir stalls and the heraldry in their carvings suggests that they were created at a later date. Several bear the Antelope Gorged and Chained, a personal badge of the Lancastrian kings which can be found on the tomb of Henry V (1386 – 1422) at Westminster Abbey, but is most often associated with his son, Henry VI (1421 – 1471). It appears on many pilgrim badges for this king who was revered as a saint after his death, although he was never canonised.

This would make the choir stalls of St Mary Magdalene contemporary to the first phase of misericords at St Laurence in Ludlow and indeed the Antelope Gorged and Chained is also found in Ludlow.

Moreover, like St Laurence, St Mary Magdalene also has an elaborately carved wooden ceiling whose roof bosses mirror some of the carvings on the choir stalls. However, unlike Ludlow the choir stalls and ceiling at Leintwardine lack any Yorkist symbolism. Or do they?

On two of the stalls is a carving which bears a striking resemblance to misericord S15 in Ludlow: a twisted ring, this one encircling a five-petaled rose. Roses are ubiquitous in medieval imagery and, according to a tourist guide for Shrewsbury, the twisted cord is a common motif in the Shropshire area, but the rose and ring motif is repeated on one of the roof bosses in the wooden ceiling where it occupies a prominent position on the central ridge, just like the falcon and fetterlock and rose within a fetterlock in Ludlow. It would therefore seem unlikely that the use of this motif is purely decorative.

But if it isn’t and if the choir stalls and ceiling date from the early or mid-15th century, then who commissioned and paid for them? The church’s main benefactors, the Mortimers, died out in the male line in 1425 and their heir Richard, duke of York was 14-year old lad who lived with his Neville in-laws in the North. Moreover, their rising political profile meant that they were increasingly absentee landlords with their last major building projects at Wigmore and Ludlow dating back to the 14th century. Indeed, a report from 1424 states that the abbey in which so many of their ancestors lay buried was in a sorry state and used by locals as a public toilet, which suggests that they hadn’t paid attention to it for some time. Did the local congregation raise the funds for the church or did the influence of the Ludlow Palmers who renovated St Laurence extend to Leintwardine? But if so, why is there no heraldic reference to the new lord as there is in Ludlow? The roses in rings on the choir stalls and ceiling are the only potentially Yorkist motifs in the whole church. The misericords were attacked with an axe during the Reformation, so perhaps some were lost, but the ceiling is fully preserved and doesn’t feature any falcons or fetterlocks.

Combining all of the above, the most likely explanation seems to be that the choir stalls and ceiling were commissioned for the chancel and nave of St Mary Magdalene where they are currently situated and installed after the accession of Henry V and before Richard, duke of York, who didn’t come into possession of all his estates as Duke of York, Earl of March and Lord Mortimer until 1432 and then appears to have focused his attention on Ludlow, had fully established himself as the new lord. So what of the roses?

The White Rose of Mortimer?

In the middle ages the rose was associated with Christ and the Virgin Mary and therefore popular as both decorative and heraldic emblem. As John Ashdown-Hill and others have noted, “Roses of three colours – white, gold and red – had certainly been used by various kings, queens, princes and princesses of the so-called Plantagenet royal family as badges since the thirteenth century.”7 These included Henry III’s queen, Eleanor of Provence, her son Edward I and Richard, duke of York’s uncle Edward, second Duke of York. But they were not the only ones. The seal of Edmund Mortimer, third Earl of March (1352 – 1381) showed his arms suspended from a rose bush in flower. Being a seal, the colour of the petals is unspecified, but C. W. Scott-Giles has claimed that the white rose was “originally a badge of the Mortimer earls of March, and was used by Earl Roger, who died in 1369”8 while Michael Powell Siddons reports that:

“A white rose is given in Writhe’s Garter Armorial as the badge of Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, a founder knight of the Order of the Garter, and a pedigree roll of Edward IV of 1461 shows that the rose was considered to have come to the House of York from the Mortimers, by descent from whom came their claim to the throne. This roll does not give a colour to this rose, and does not attribute any rose to the House of Lancaster. Another pedigree roll of Edward IV is freely decorated with the white rose en soleil, but without any indication as to which family it came from. Some later sources give the Mortimers’ badge as a rose per pale Argent and Gules. It is noteworthy that although the will of Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, quoted below, mentions several items decorated with roses, none of these are white. In the lists of the badges of the Duke of York (sometimes given as those of Edward IV), the earliest of which probably date from before 1460, the white rose is given as a badge for the castle of Clifford, which came to the House of York through the second marriage of Richard, Earl of Cambridge (exec. 1415), with Maud, daughter of Thomas, Lord Clifford.”9

Indeed, the contemporary list of heraldic badges used by Richard, duke of York which associates the sunburst with Richard II also associates the white rose with Clifford Castle. Unfortunately, how the rose badge came to be associated with the castle is unknown and the building itself offers no clues as it lies in ruins. However, the Maud Clifford who was the heiress of Clifford Castle married not Richard, earl of Cambridge, but first William Longespee, earl of Salisbury, and after his death John Giffard of Brimpsfield, after whose death in 1299 (!) it passed through her daughter Margaret, countess of Lincoln, to the earldom of Lincoln and then in the 14th century to the Mortimers of Wigmore.10 It therefore probably came to the house of York through Anne or Edmund Mortimer.

As descendants of both the Plantagenet royal family and the Mortimers the house of York could have inherited its rose badge from either or both these sources, but the absence of any Yorkist heraldry in Leintwardine and the fact that the red rose of Lancaster hadn’t been invented yet seems to suggest that the roses at St Mary Magdalene don’t refer to either Richard, duke of York or Henry VI. Moreover, John Ashdown-Hill has pointed out that, with the exception of one poem which must date from before 1460 since it mentions the Earl of Salisbury who died at the battle of Wakefield, in contemporary political poems the white rose of York “is not explicitly related to Richard, Duke of York, himself. Instead, York’s personal badge is generally referred to as the fetterlock. For example, a poem on the battle of Northampton (10 July 1460) speaks of ‘certeyne persones þt late exiled were, … þe Rose (Edward, Earl of March), þe Fetyrlok (Richard, Duke of York), þe Egle (Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury) and þe Bere (Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick)’.” Instead “the Yorkist rose often appears to have been seen specifically as the badge of Edward, Earl of March, eldest son of the Duke of York – the future King Edward IV” who wasn’t born until 1442, didn’t move to Ludlow until the 1450s and didn’t lay claim to the throne until after his father’s death in 1460.11 This would tie in with the presumed timing of the building work at St Mary Magdalene and the two stages of renovation at St Laurence’s. It therefore seems not unreasonable to suggest that the rose badge was originally used by the Mortimers and adopted by their Yorkist heirs around the time when Richard, duke of York began to lay claim to the throne of England.

Conclusion

The youthful years Edward IV spent with his brother in their household at Ludlow Castle seem to have left a deep impression on him since he established a similar routine for his own son, Edward V, and his daughter, Elizabeth of York, later followed the same pattern for her son, prince Arthur Tudor, whose heart is buried in St Laurence’s. Perhaps they also inspired him to brand the house of York by marrying a rose badge used by his Mortimer ancestors, including his father Richard, Duke of York, Earl of March and Lord Mortimer, with the sunburst of Richard II, just like Henry VII branded the Tudors by marrying the white rose of York to the (fictional) red rose of Lancaster. After all, he also adopted other Mortimer badges, such as the white lion of March which he kept using even after he had become king of England, for example on livery collars, and medieval nobles who, thanks to intermarriage, were often spoilt for choice when it came to arms and heraldic badges, usually chose to emphasise their most illustrious connections. In Edward’s case they would have been those upon whom he based his claim to the throne of England. As John Ashdown-Hill has concluded:

“If Edward IV did indeed derive his use of the white rose badge via his Mortimer ancestry, together with his claim to the throne, then his marrying of it with the sunburst emblem which had been a badge of Richard II, whether or not this was inspired by the triple sun phenomenon seen at the battle of Mortimer’s Cross, looks very much like a powerful legitimist statement in symbolic form.”12

Livery collar of suns and roses with the lion of March, tomb effigy of Sir Richard Herbert of Coldbrook, Abergavenny

I would like to thank the Mortimer History Society for their encouragement and patience with my many questions.

Sources & Further Reading:

- Peter Klein: “THE MISERICORDS & CHOIR STALLS AT ST LAURENCE’S CHURCH, LUDLOW”, Ludlow (2015)

-

David Lloyd, Ewart Carson & Don Beattie: “THE PARISH CHURCH OF ST LAURENCE, LUDLOW”, Ludlow Parochial Church Council (2014)

-

Philip Hume: “ON THE TRAIL OF THE MORTIMERS”, Logaston Press (2016)

-

John Challis: “WIGMORE ABBEY – THE TREASURE OF MORTIMER”, Wigmore Books (2016)

-

John Ashdown-Hill: “THE RED ROSE OF LANCASTER?”, The Ricardian, vol. 10 (June 1996), pp. 406–420

-

John Ashdown-Hill: “THE WARS OF THE ROSES”, Amberley Publishing (2015)

-

Thomas Penn: “HOW HENRY VII BRANDED THE TUDORS”, The Guardian (2 March 2012) https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/mar/02/tudors-henry-vii-wars-roses

-

Laura Blanchard: “THE EDWARD IV ROLL – THE ROLL ONLINE”, Richard III Society American Branch http://www.r3.org/on-line-library-text-essays/the-edward-iv-roll/the-roll-online/

-

Free Library of Philadelphia: “CHRONICLE OF THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD FROM CREATION TO WODEN, WITH A GENEALOGY OF EDWARD IV” https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/3310

-

Thomas Penn: “HOW HENRY VII BRANDED THE TUDORS”, The Guardian (2 March 2012) ↩

- C William Marx: “AN ENGLISH CHRONICLE 1377-1461”, Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales MS 21068 and Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Lyell 34 ↩

- John Ashdown-Hill: “THE WARS OF THE ROSES”, Amberley Publishing (2015) ↩

- ARCHOEOLOGIA vol. xvii, p.226, citing Digby MSS No. 28, quoted in Caroline Halsted: “RICHARD III AS DUKE OF GLOUCESTER AND KING OF ENGLAND, volume 1, pp. 404-5 ↩

- Zenonian: “YORK OR LANCASTER: WHO WAS THE RIGHTFUL KING OF ENGLAND? PART 2 – FOR A KINGDOM ANY OATH MAY BE BROKEN – YORK’S TITLE 1460”, Murrey and Blue https://murreyandblue.wordpress.com/2015/10/19/york-or-lancaster-who-was-the-rightful-king-of-england ↩

- V. J. Scattergood: “POLITICS AND POETRY IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY”, Barnes & Noble (1971), p. 189 ↩

- John Ashdown-Hill: “THE WARS OF THE ROSES” ↩

- C. W. Scott-Giles: “SHAKESPEARE’S HERALDRY”, Heraldry Today (1971) ↩

- Michael Powell Siddons: “HERALDIC BADGES IN ENGLAND AND WALES”, Vol. II, part 1, Boydell Press (2009), p. 211. ↩

- “A HISTORY OF CLIFFORD”, Clifford Parish Council (2008) and “DETAILED HISTORY OF CLIFFORD CASTLE EARLY OWNERSHIP” http://cliffordcastle.org/?page_id=177 ↩

- John Ashdown-Hill: “THE WARS OF THE ROSES” ↩

- John Ashdown-Hill: “THE RED ROSE OF LANCASTER?”, The Ricardian, vol. 10 (June 1996), p. 410 ↩