Lady on Horseback, mid-15th c., British Museum

For me, being a “Ricardian traveler” doesn’t necessarily mean that you only visit places where Richard III — as a child, the Duke of Gloucester or the King — lived. It means exploring towns, castles, battlefields, and churches which have some association to his family or to the Wars of the Roses. I would call Conisbrough in South Yorkshire a “Ricardian” site because it does have connections to Richard’s ancestors, including a rather infamous one! And, to my surprise, I discovered that Richard did give its castle some attention during his life, consistent with his reputation as being a Duke who made extensive investments in architecture and his estates’ infrastructure.

Conisbrough Castle

From the 11th to the 14th century, Conisbrough Castle was in the possession of the de Warenne Earls of Surrey. Construction began in the late 11th century, with the unique great tower (also called “Hamelin’s Tower” after Hamelin de Warenne, Henry II’s half-brother) being built in the 1170s or 1180s.

Conisbrough Castle

Conisbrough Castle – Barbican and SW Curtain Wall

The great tower contained living quarters for its early inhabitants: a great chamber for receiving guests, a bedchamber, chapel and latrine. “Mod cons” such as a well and fireplaces provided fresh water and heat. The fireplaces have unique “joggled” (V-shaped) lintel stones and intricately carved capitals in the French style, similar to examples at York Minster (completed by 1175). The castle anchored a burgeoning human settlement on the River Don, and there are lovely views of Conisbrough village from the roof of Hamelin’s Tower.

Conisbrough Castle passed to the crown (Edward III) when the de Warenne family line ran out of surviving heirs. The king granted it to his son Edmund of Langley, first Duke of York. While Fotheringhay and Ludlow were primary Yorkist residences, Conisbrough was an important secondary residence. It was at Conisbrough Castle that Langley’s second son, Richard, was born in 1385. Richard II served as his god-father, as the king was staying in York at the time.

Richard of Conisbrough is a controversial historical figure. There are, and were, significant doubts about his birth legitimacy. He was conceived 12 years after his older brother Edward when his mother (Isabella of Castile) was rumored to have been having an extra-marital affair with Richard II’s half-brother, John Holland, Earl of Huntingdon. Further doubt is cast on his legitimacy by his father and brother neither mentioning nor providing him with any land or income in their wills. In a secret and clandestine marriage, he took the 16-year old Anne Mortimer, eldest sister of the Earl of March and Richard II’s declared heir, as his wife. Aside from receiving an annuity of 500 marks from Richard II, and later the title of Earl of Cambridge in 1414 from Henry V, Richard was the poorest of all English earls and held no political or military office. His “claim to fame” came in 1415 when he was executed for his role in the Southampton Plot, a poorly devised scheme to assassinate Henry V and put his brother-in-law, Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, on the throne. Notably, some historians and scholars have questioned whether any such cohesive conspiracy existed. They suggest that Henry V might have gotten wind of grumblings amongst some noblemen and, in an effort to eradicate political turmoil before he left for his campaign in France, accused them of plotting against his life. A confession was obtained from one of the alleged co-conspirators (Sir Thomas Grey), but Richard of Conisbrough demanded a trial by his peers. He was found guilty.

His second accomplishment is that he and his wife Anne Mortimer produced one male child, also named Richard, who later became the third Duke of York and the father of two kings (Edward IV and Richard III). Although the English Heritage guidebook states that the future third Duke of York was born at Conisbrough Castle, this is not documented by baptismal records there. Anne Mortimer died either while giving birth to Richard in 1411 or shortly thereafter, when she was around 20 years of age. There are no records about where she died or was buried, but there is a theory that she was interred at King’s Langley in Hertfordshire. Her skeleton was found during an exhumation of Edmund of Langley’s tomb in 1877. It was during the disinterment of Langley’s remains, which were intermixed with those of his first wife Isabella, that archeologists discovered a separate lead coffin containing the skeleton of a young woman less than 30 years of age with auburn hair. The scientists concluded it could not belong to Langley’s second wife, Joan Holland, since she died at the age of 53/54 after remarrying several times. Of course, no DNA or other forensic testing was done back in the Victorian days, so this conclusion is based on the educated guesswork of archeologists. It is possible that Anne gave birth to Richard and died at Conisbrough Castle, with her body being translated more than 150 miles to Kings Langley, but again there is no record of this happening. There is some logic to the argument that she would have been buried near her place of death, thus making Conisbrough a less likely candidate.

With the accession of Edward IV to the throne in 1461, the castle again became a crown property. The last recorded repairs to it were carried out in 1482-3, on the orders of Richard, Duke of Gloucester. After the Battle of Bosworth, it fell into a ruinous state and remained in that condition for hundreds of years. Yet, for many, the castle has inspired the imagination. Both Geoffrey of Monmouth (Historia Regum Britanniae) and Sir Walter Scott (Ivanhoe) used Conisbrough Castle as a setting for their storied flights into English history.

The Church of St Peter, Conisbrough

Perhaps one of the more surprising “gems” discovered on the trip to Conisbrough was the parish church of St. Peter’s, which boasts architectural details from the Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman periods.

St. Peters Church, Conisbrough

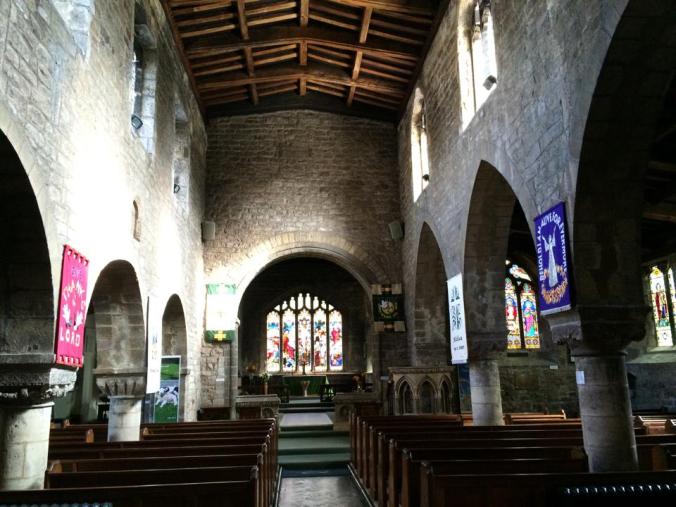

Nave of St Peters Church, Conisbrough

The church was founded in the 8th century, built around 740-750 AD and more likely even as early as 680 AD based on masonry construction similarities with other churches dating from that period, making it one of the oldest parish churches in all of England. One of the arch capital supporters in the nave came from a nearby Roman villa, and it features a carving of a Roman soldier with a leather-pleated skirt; it was later defaced by 16th century iconoclasts, but it is still visible today. The nave itself has round Saxon arches on the north side, and pointed Norman arches on the south side from the 1200 period. The nave’s roof was raised in 1200 and again 1475, when the church was being substantially remodeled in the Perpendicular style during the reign of Edward IV, to its present height. The Victorians enlarged the north aisle in 1866, keeping the original stones and some ancient 13th century glass windows which depict Old Testament figures such as Joseph, Noah and Jacob. Unfortunately, their work was met with scorn and ridicule, and it seems they may have caused the loss of some ancient frescoes and wall paintings. A 13th century altar slab, with its 5 consecration crosses, presently in the north presbytery chapel, was found in the Castle ruins in 1923 and brought into the church where it is used for prayer.

There is a most curious tomb chest that is said to be from the Romano-British time period, a leftover from when Aurelius Ambrosius remained in Conisbrough following the withdrawal of Roman governors in 400 AD and preached in what is now the churchyard. According to the history recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth, he gathered and led the Britons against the invading Saxons. The tomb chest depicts (from right to left) a dragon, a serpent, a knight with sword and shield defending against the dragon, and a priest with a bishop’s crozier. Other experts say that Geoffrey of Monmouth’s history is suspect and more fantasy than fact, and the chest actually dates from the Norman period.

Tomb Chest: Romano-British or Norman?

Remnants of 15th century glass have been assembled into two collages in the windows of the south wall of the chancel. One contains a depiction of the Blessed Virgin Mary, with tears streaming from her face, as she knelt at the crucifixion of Jesus. The other contains a portrait of Prior Thomas Atwell from Lewes Priory in Sussex and a figurehead of St Blaise with his bishop’s crozier.

For more information, including visiting hours, about Conisbrough Castle, click here and here.

The parish church of St Peter has a 20-minute video about its history on its website, which you can find here.