Lady on Horseback, mid-15th c., British Museum

My husband and I had the good fortune to spend two weeks in England and Wales in October, 2017. I had been asked to moderate a conference about Richard III and 15th century warfare at the Leicester Guildhall, sponsored by the Richard III Foundation. During our stay in Leicester, we drove into Northamptonshire in order to explore a small parish church at King’s Cliffe that purported to have a number of objects from Richard III’s birthplace of Fotheringhay. What we discovered surpassed all our expectations.

Scene of Destruction: St Mary and All Saints Church

Like many tales of discovery, this one begins with a tale of loss. The year was 1566. Queen Elizabeth I was on progress through her realm, having already occupied the throne for 8 years. Her itinerary took her to Fotheringhay Castle, a short distance from the parish church dedicated to St Mary and All Saints. A romantic version of the story says she visited St Mary’s and saw (with horror) a number of desecrated and shattered tombs, including those of her ancestors — the second Duke of York, the third Duke of York, his Duchess Cecily, and their son Edmund Earl of Rutland.

The choir in which they had been buried had been ransacked during Henry VIII’s program to dissolve monastic houses, chantries, and collegiate churches. The Queen allegedly expressed disgust at the lack of respect shown towards the burial monuments of her Yorkist ancestors, so she set up a commission to assess and “renovate” the damage. During that process, the choir was torn down, her ancestors’ remains were removed to the nave, and two grand 16th-century style monuments were erected over the relocated burials. According to this version of the story, Elizabeth I is portrayed as a magnanimous benefactor and savior of Fotheringhay’s church and its royal burials.

Like all good tales, there is a lot about this story that is more fiction than fact. In 1560, Elizabeth I had been forced to bring a proclamation to halt attacks on tombs and royal monuments in the wake of her father’s legislation requiring the destruction of religious imagery. It is unlikely that she personally visited Fotheringhay’s church in 1566 and more likely that she heard about its parlous condition from local Northamptonshire gentry at whose manors she had been accommodated during her royal progress. If she had been appalled or disgusted, it did not prompt her to act urgently as it wasn’t until 1572 that steps were taken to deal with the matter.

The parishioners, who were invited to weigh in, wanted to keep the choir. They submitted a report showing that it could be repaired for about Ł52. They volunteered to assume the expenses of maintaining it thereafter. Although they agreed that the Lady Chapel to the east of the choir was beyond repair and should be demolished, it was determined that the materials from its rubble could be sold for Ł94 6s 0d. This, they said, had the added benefit of allowing the tombs of the Queen’s ancestors to remain undisturbed in their original locations.

The Queen’s commissioners, however, submitted a very different report, concluding that the entire eastern part of the church, including the choir, Lady Chapel, and their aisles, was unsalvageable and would cost more than Ł100 to repair. The salvage value of its materials, they determined, would bring in Ł252. Ironically, their assessment proved that the walls of the choir, Lady Chapel, and aisles were structurally sound, and their wood and lead roofs still intact, as they determined that lead salvaged from the demolishment would fetch Ł200. No mention, however, is made of any monuments to be built over the relocated Yorkist tombs; it seems the commissioners envisioned iron grates being erected around them. The total cost of removing and re-siting the burials was estimated at about Ł10.

Ultimately, it was the plan of the Queen’s commissioners that won out. The entire eastern part of St Mary’s church was demolished in 1573. The sale of lead, timber, doors, glass, and loads of stone is itemized together with the wages of the masons and laborers who built the wall closing off the nave. It is now believed that the Queen did not even pay for the monuments that now stand over her ancestors’ remains; rather, Sir Edmund Brudenell (one of the commissioners) likely retained a team of masons for their fabrication at his own expense. St Mary’s, once intended by the Yorkists to be a large and magnificent collegiate church with a master, 8 clerks, and 13 choristers who lived in a richly-cloistered environment, was now a truncated and much-reduced shadow of its former self.

Fotheringhay Church

Scene of Preservation: The Parish Churches of Tansor, Hemington, and Benefield

Despite this sad story of loss, it may be comforting — if not surprising — to know that original woodwork and painted glass from Fotheringhay can still be found nearby. The sale of materials of the dismantled choir in 1573 led to the dispersal of its woodwork to the parish churches at Tansor, King’s Cliffe, Benefield, Hemington and Warmington. Misericords at Tansor and Hemington display Yorkist heraldry, including the well-known falcon-and-fetterlock badge of the third Duke of York. Hemington even has a misericord showing two boars. The boar, as we know, was chosen by Richard as Duke of Gloucester for his badge. This has led at least one investigator to conclude that Richard III “almost certainly donated the splendid set of choir stalls from Fotheringhay which are now in Hemington church (Northants): his boar device occurs twice on them”. [Marks, p. 82] However, H. K. Bonney, in his Hist. Notes on Fotheringhay (1821) said the stalls were left by will to Hemington church by a farmer of Fotheringhay in the 18th century. Bonney received this information from a Rev. F. H. La Trobe.

At Benefield, three carved misericord seats, said to have come originally from Fotheringhay church, were purchased at Tansor in 1899 and placed in the chancel, one on the north and two on the south side.

Misericord w/ Roses & Grotesque (Benefield)

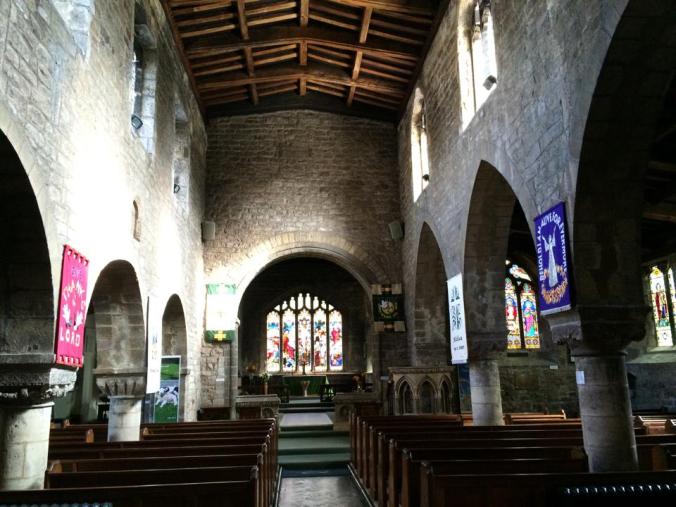

The Parish Church at King’s Cliffe

The parish church dedicated to All Saints & Saint James at King’s Cliffe is particularly of interest, as it has not only woodwork from Fotheringhay but also original painted window glass. The woodwork consists of panels of a uniform design, and were probably used at Fotheringhay as stall ends or elsewhere in the fabric of the choir. The parishioners at King’s Cliffe now use these wooden panels as pew ends. They appear to be remarkably similar to wooden panels recently repatriated to Fotheringhay from Tansor. (The panels from Tansor are now on display at Fotheringhay, and are undergoing restoration.) At Warmington, the parish church appears to have acquired similar wood panels, but has painted them in Art Nouveau colors.

There is also a pulpit at King’s Cliffe constructed from 15th century wood from Fotheringhay. Before 1896, it was a much grander, three-tiered reading desk with pulpit. A booklet at King’s Cliffe describes how it would have appeared in the early 19th century when its Rector, H K Bonney, took extensive notes:

The materials of which the Desk and Pulpit are composed are oak panels with good tracery, brought from the Nave of the Church at Fotheringhay in 1813. The base is divided into panels, ornamented with quatre foiles, arches and mouldings, and terminated with foliage. Above this rises the desk for the Prayer Book and Bible, decorated with four panels of well-executed tracery formerly on the seat appropriated to the inhabitants of the Castle at Fotheringhay. Above all is an octagonal Pulpit, the panels of which are similar to the ends of the Free Seats, standing upon a base which bears three shields. [The Free Seats had been installed by Bonney in King’s Cliffe church at the same time as the three-deck pulpit]. In the centre are the armorial bearings of the present Rector [H K Bonney himself] – on a bend three fleur de lys, and on each side these inscriptions: “From Fotheringhay, of the date of 15th century” and “Erected by H K B Rector 1818”.

The Pulpit is surmounted by a rich Canopy corresponding with itself, ornamented by Pendants and Finials, with Arches, enriched with tracery between them.

In putting up the Free Seats, the Parish was assisted by the donation of Mrs Bridget Bonney, the Rector’s mother.

The painted glass at the East and West ends was chiefly collected from the refuse of the windows at Fotheringhay.

The surviving pulpit retains only the octagonal structure, but a drawing made by H K Bonney illustrates how it appeared in the early 19th century:

The painted glass is even more fascinating, since glass is such an ephemeral and easily damaged object. A number of “quarries” (small, diamond-shaped panes) show fetterlocks, roses, oak leaves, roses-en-soleil, and suns — distinctive badges of the Yorkists.

Other windows at King’s Cliffe show angels playing instruments, and various animals and birds. According to Marks, their dimensions correspond with those of the tracery lights in the Fotheringhay aisle windows, further confirming their provenance.

A window in the north aisle at King’s Cliffe has 15th century glass, also believed to be from Fotheringhay:

Possible 15th Century Glass at King’s Cliffe

King’s Cliffe is a short, 10-minute drive from Fotheringhay, and is worth a visit for any Ricardian. The church has many delightful medieval artifacts, including carved corbels in the shape of human faces, and gargoyles in the shape of fanciful animals.

Much of the church was constructed in the 15th century, and it fortunately survived the destruction of churches that occurred during the Reformation movements of the 16th and 17th centuries. One can definitely get a good idea of how a parish church was built during the life of Richard III. And, if one’s imagination is active enough, you might even feel the spirit of his birthplace and the “Yorkist Age” speaking through its Fotheringhay artifacts.

King’s Cliffe Parish Church

Blog author: Susan Troxell; photo credits – Susan Troxell.

Further Reading:

“Fotheringhay.” An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1984. 63-75. British History Online. Web. 6 November 2017. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/pp63-75.

“King’s Cliffe”, in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire (London, 1984), pp. 91-106. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/pp91-106 [accessed 30 October 2017].

Richard Marks, The Glazing of Fotheringhay Church and College, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 41:1, 79-109 (1978)

Sofija Matich and Jennifer S. Alexander, Creating and recreating the Yorkist tombs in Fotheringhay church (Northamptonshire), Church Monuments, Volume XXVI, pp. 82-103 (2011)