Lady on Horseback, mid-15th c., British Museum

Dartington Hall, near Totnes in Devon and just southeast of Dartmoor National Park, represents a uniquely British form of historical contradiction. It is both medieval, having parts of a Grade I-listed late 14th century manor house, and modern, being the current home of the Schumacher College and formerly the site of a progressive coeducational boarding school which broke all the molds of English education and even attracted the attention of MI5. Today, it operates a hotel, restaurant and conference center, and has Grade II* listed gardens.

Our visit was prompted by the prospect of staying briefly in the house built between 1388-1400 by John Holland, first earl of Huntingdon and duke of Exeter. The Holland dukes of Exeter were themselves highly controversial figures and their history is closely intertwined with that of the Houses of York and Lancaster. We didn’t expect, however, that we’d discover an architectural feature that would refute one of the more commonplace myths of the “Wars of the Roses”.

Step-Brother to a King, Builder of a Great House

Approaching Dartington Hall, the first thing one notices is that it is not a fortified structure and was not built with a military purpose in mind. There are no battlements or curtain walls, no remnants of motte or bailey. There is an “entrance block” consisting of a two-story building with only doors instead of a portcullis. The visitor enters a large, green quadrangle, at the end of which is the magnificent Great Hall with its crenelated porch.

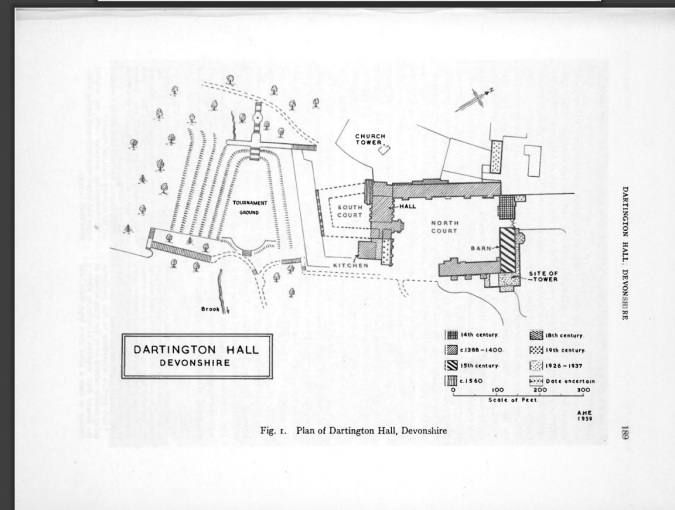

Plan of Dartington Hall from Anthony Emery’s text

14th c. Great Hall with Porch Entrance – Dartington Hall

Along the western edge of the quadrangle is a wing that contains several apartments and garderobes. Beyond the Great Hall was another quadrangle that faced a tiltyard or tournament grounds. In all, the impression is that this was a lavish residence for a very great lord who had numerous retainers and who liked to joust. Like Richard III, John Holland generates polarized opinions, with some viewing him as viciously capricious and others as valiant and misunderstood. The story of John Holland and his heirs, is an integral part of the conflicts between the “Red Rose of Lancaster” and the “White Rose of York”.

He was born one hundred years before Richard III, in 1352, the son of Joan, Countess of Kent, who later married the Black Prince. Thus, he was an older, half-brother to Richard II and part of the extended royal family. His early fame came as a soldier and jouster, but he also had a temper that could get him into trouble. In fact, according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, his first “political act” was to murder a friar who had accused John of Gaunt of conspiring to kill the 17-year old Richard II. As a young man, Holland was very much under the sway of John of Gaunt, the latter being the senior uncle to the king and probably the wealthiest magnate in England, if not its most influential. Holland even seduced Gaunt’s daughter Elizabeth and got her pregnant before he married her. But his relationship with Gaunt cooled, and Richard II became his patron instead. The favor he received was so extravagant (and included an earldom and dukedom) that Holland memorialized it by having Richard II’s white hart badge constructed as a roof boss in the entrance porch at the great manor house he was building at Dartington Hall. Its location meant that every visitor who was received into his great hall would see Holland’s overt connection to the king.

Late 14th c. Roof Boss showing Richard II’s Badge on Cinquefoil Rose

From Royal Patronage to Treason

Things would not go well for Holland’s new patron, however. When Richard II and Holland returned from a military campaign in Ireland in 1399, they were greeted with troops gathered by Gaunt’s son, Henry of Bolingbroke, who forced the king’s abdication. Holland attended the Parliament which formalized Richard II’s deposition, and attended the coronation of Bolingbroke as Henry IV – the first Lancastrian king. While he officially renounced his allegiance to Richard II, Holland suffered the loss of many lands and titles previously given to him, and hardly three months had passed before he was conspiring with others to assassinate Henry IV and restore Richard II in the “Epiphany Rising”. The plot was foiled, Holland fled, but he was caught and executed without trial by one of Henry IV’s allies.

John Holland lost his life at the hands of Henry IV’s Lancastrian faction. So, one might ask, why does the Dartington Hall roof boss depict the “Red Rose of Lancaster”? Does it represent a contradictory tribute to both of Holland’s patrons, Gaunt and Richard II?

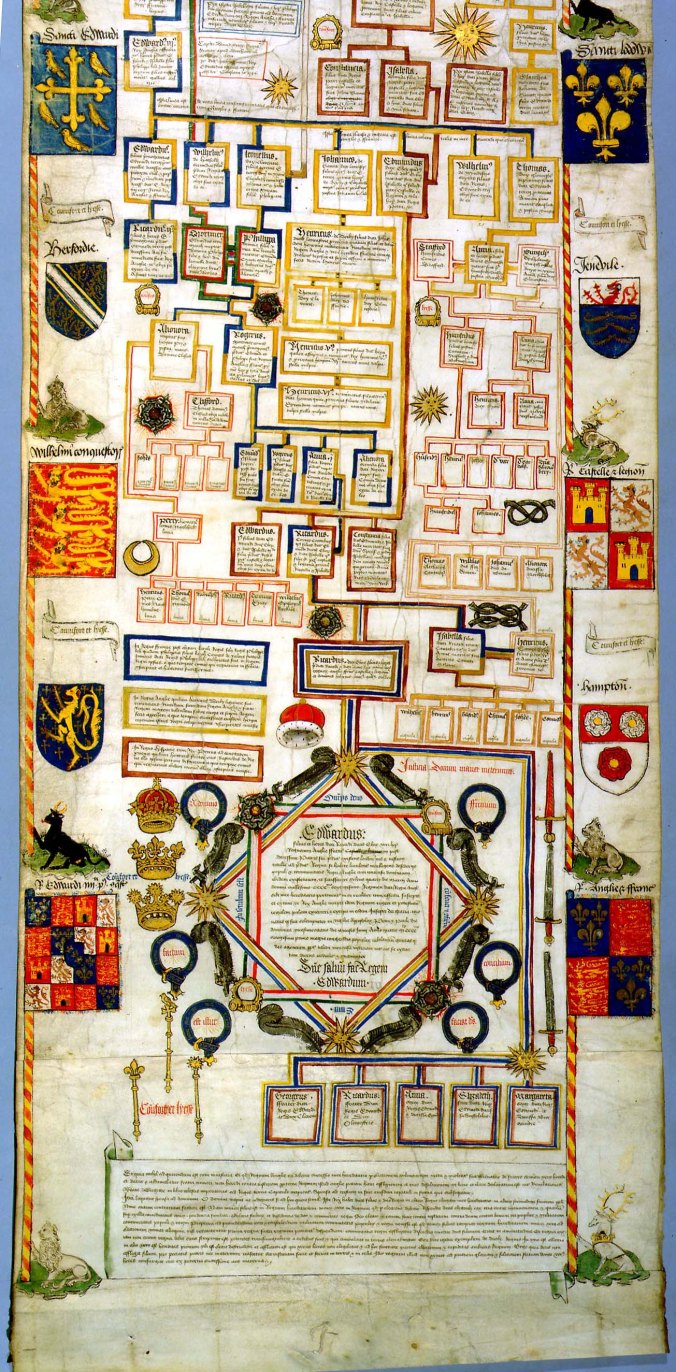

One explanation lies in the 20th century restoration of Dartington Hall. Having fallen into rack and ruin, the property was purchased by Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst in 1925, and they retained a well-credential architect to restore and modernize it. While working on the porch to the great hall, they discovered the roof boss which also helped to determine it was built during the last decade of Richard II’s reign. The engorged (chained) white hart, or white hind, was a well-known badge adopted by the king in the late 1380s; it would come to be associated with him in the following century and even used by the Yorkists to symbolize their claim as rightful heirs to Richard II. It is most prominently displayed in the “Edward IV Roll”, a genealogical document published in 1461 following Edward IV’s defeat of Henry VI at Towton.

Edward IV Roll – Showing Richard II’s Badge at Mid- & Lower Right

The Dartington boss depicts Richard II’s badge on top of a five-petaled or “cinquefoil” heraldic rose, a symbol that by the 20th century had become synonymous with the “Wars of the Roses”. Notably, there was no pigment left on the roof boss when it was discovered, so it was gilded and painted with colors they thought would have been suitable. That they painted the heraldic rose red was most likely because of the association of the red rose with the House of Lancaster. This association was made famous in a scene in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part I in which Somerset (a Lancastrian) and York argue in the Temple garden, and they pick, respectively, a red rose and a white rose to represent their competing interests. It has been part of historical mythology ever since. Undoubtedly, the Dartington Hall restoration team were aware of this mythology, and they were probably aware of the connections that later developed between the second and third dukes of Exeter and the Lancastrian kings of England.

Loyal to Lancaster, Married to a Yorkist

Following his execution in 1400, Holland was succeeded by his son John, who styled himself the earl of Huntingdon and would later receive the title of duke of Exeter from Henry VI by virtue of his loyal service. John fought at Agincourt with distinction and was on the tribunal which tried and sentenced to death those accused of the Southampton Plot. One of those to be executed was Richard III’s grandfather, the earl of Cambridge. Despite his pedigree, he was poor in resources and never had adequate funds to support his station in life. Nevertheless, he served on the royal council, was present for Henry VI’s coronation in France, served on the tribunal that declared Eleanor Cobham a witch, and was able to marry himself to high-born widows, including a Mortimer. In all, he was a solid Lancastrian, but died in 1447 before a series of crises arose from Henry VI’s mental incapacity and political divisions with the third duke of York. He also lived to see his son and heir, Henry, marry Anne, the duke of York’s eldest daughter, in 1446.

Henry and Anne had probably one of the strangest marriages of the day, a union of Lancastrian and Yorkist children, one whose father had ordered the execution of the other’s grandfather. Henry Holland was in the line of succession to the childless Henry VI in 1446 because he was a great-grandson of John of Gaunt. This made him an appealing marriage prospect, so York was willing to pay the destitute Holland 4,500 marks for the privilege. Anne was only 6 years old at the time; Henry was 15. They had one child, a daughter called Anne, but their marriage was a disaster. Holland was cruel and violent, and remained a staunch Lancastrian. After the birth of their daughter, they lived separately and Anne took on a lover, Thomas St Leger. Holland fought for Henry VI at the Battle of Barnet and was left seriously injured, believed to be dead. He somehow crawled to a nearby abbey and managed to survive. His marriage did not. Anne was granted a divorce in 1472 and she married St Leger. Holland served in Edward IV’s 1475 military campaign to France, but on his ship back to England, he fell overboard in the Channel and drowned to death, some saying he had been forced overboard at the order of the Yorkist king.

Following the death of Exeter, Dartington Hall passed to his former wife Anne, who was now married to St Leger. St Leger was a Yorkist under Edward IV but betrayed Richard III in October, 1483 when he conspired with the duke of Buckingham to remove him from the throne. By this time, Anne of York had already died. St Leger was executed, attainted, and his estates – including Dartington Hall – reverted to Richard III as crown property. When Richard III was killed at Bosworth, Dartington was given as a life-estate to Henry VII’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, who apparently never visited but did derive income from the estate. It reverted to Henry VIII as a crown possession upon her death. Thus, Dartington Hall was owned, at different times, by people who represented almost all the factions comprising the “Wars of the Roses”.

Is that the Red Rose of Lancaster?

It might be tempting to see the Dartington heraldic rose as the “Red Rose of Lancaster”, but there is a significant problem with that theory. It was built in the last decade of the 14th century, too early to have any associations with the “Wars of the Roses”, which at the earliest would be dated to Richard II’s deposition in 1399. We can also rule out its construction in the 15th century. The second and third dukes of Exeter were devoted to the Lancastrian kings and would have no reason to display the badge of a monarch who they had deposed. Dartington Hall was possessed by the Yorkist, St Leger, from 1475-1483, but there is no indication that he initiated any building projects there. And while the Tudors owned the estate from 1485 on, there is similarly no evidence that they made any renovations to the Great Hall or its porch, and there is still no further evidence of the Tudors combining the badge of Richard II with the Lancastrian red rose. Therefore, the only conclusion to be reached is that the Dartington roof boss contains imagery that contemporaries of Richard II associated with him, including the rose.

Cinquefoil roses were used by Plantagenet royalty in diverse circumstances, not necessarily all heraldic. Although there is some controversy as to when the rose first became a royal English badge, the modern thinking is that Henry III’s queen, Eleanor of Provence, brought it with her. Both sons of Henry III and Eleanor used rose badges of uncertain color; it is said that Edward I’s was gold with a green stem and Edmund “Crouchback”‘s was red. Edward III’s sixth Great Seal employed roses as background detail. The effigy of the Black Prince at Canterbury Cathedral incorporates gold roses on his armour and on the lower edge of the tester over his tomb. John of Gaunt gave St. Paul’s Cathedral a bed powered with decorative red roses, and Henry IV’s tomb effigy at Canterbury Cathedral has blue roses decorating his mantle. Coinage produced during Henry IV’s reign briefly employed a rose figure as a stop between words. All of this suggests that the device of the rose, of various colors, was generally employed from the time of Henry III through his great-grandson Edward III and his heirs. There was no specific association between John of Gaunt or his sons and the color red.

In fact, while there is a long-standing belief that the Earls of Lancaster adopted the red rose badge ever since Edmund “Crouchback” first used it, there is no contemporary 14th or 15th century evidence that the House of Lancaster followed this precedent. In his seminal article, “The Red Rose of Lancaster?” published in The Ricardian (June 1996), Dr John Ashdown-Hill demonstrated that the first account of the red rose being associated with Lancaster came early in the reign of Henry VII, the first Tudor king, as part of a visual propaganda to cast him as a unifier between two dynastic houses symbolized by red and white roses. But, as Ashdown-Hill observes: “None of the three Lancastrian kings can be proved to have used such an emblem, even if they were entitled to it, and this is in striking contrast to the white rose badge of York, for which ample contemporary evidence can be provided.” Portraits of Henry IV, V and VI are either devoid of any rose badge or were painted well into the Tudor period. A Tudor-period book depicts Henry IV’s battle standard as having red roses on a white background, but this has never been authenticated. The same is true for a Tudor-period account of Henry V’s funeral hearse, which allegedly had a valence of red roses. Indeed, when Henry VI briefly regained his throne in 1470-71, he removed Edward IV’s heraldic rose and sunburst mint marks on coinage and replaced them with a fleur de lis.

Dartington Hall’s roof boss substantiates Dr Ashdown-Hill’s proposition that the rose was not a peculiarly Lancastrian badge before or during the “Wars of the Roses”. Richard II was not the Earl or Duke of Lancaster, and was not on particularly good terms with Gaunt or Bolingbroke in his last decade of life. The only sound conclusion one can draw is that the cinquefoil rose was one of Richard II’s devices, perhaps not as well known, but the memory of this – like much of history – was rewritten by the victorious Tudors.

Bibliography

John Ashdown-Hill, “The Red Rose of Lancaster?” The Ricardian, June 1996, pp. 406-420.

John Ashdown-Hill, WARS OF THE ROSES (Amberley, 2015)

Henry Bedingfeld, Peter Gwynn-Jones, HERALDRY (Brompton, 1993)

Anthony Emery, “Dartington Hall, Devonshire”, http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1132-1/dissemination/pdf/115/115_184_202.pdf

Griffiths, R. A.. “Holland , John, first duke of Exeter (1395–1447).” R. A. Griffiths In OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, edited by H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed., edited by David Cannadine, January 2008. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13530 (accessed August 2, 2016)

Hicks, Michael. “Holland, Henry, second duke of Exeter (1430–1475).” Michael Hicks In OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, online ed., edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: OUP, 2004. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50223 (accessed August 2, 2016)

Stansfield, M. M. N.. “Holland, John, first earl of Huntingdon and duke of Exeter (c.1352–1400).” M. M. N. Stansfield In OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, edited by H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed., edited by David Cannadine, January 2008. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13529 (accessed August 2, 2016)