Putting aside the mystery of what ultimately happened to Edward IV’s two sons, one enduring difficulty for a student of history is whether Richard III used the proper legal procedure in having them declared illegitimate because of their father’s precontracted marriage to Eleanor Talbot. The most (and only) significant defect appears to be the failure to refer the issue to a church court for determination.[1] But it seems no one has fleshed out how an ecclesiastical tribunal would have litigated such an extraordinary and unprecedented matter, let alone identified which church court would have had authority to hear it.

As a retired litigator of 20 years, I undertook the challenge of researching medieval English church court procedures and precedent cases to answer four questions: Which church court would have decided the precontract issue? How would it have conducted the litigation? What evidence would it have heard? How conclusive would its decision have been? They seemed like simple questions, but they were not. Along the way, I learned not only about the unique relationship of English church and state when it came to addressing marriage and inheritance matters, but also about a thicket of procedural issues that an ecclesiastical tribunal would have presented in 1483, the sum of which may help explain why it wasn’t referred there in the first place.

A Claim that Involved Both Canon and Secular Law

The Crowland Continuator wrote that Richard III’s title to the throne was first put forward on 26 June 1483 when he claimed for himself the government of the kingdom and ‘thrust himself’ into the marble chair at Westminster Hall. The ‘pretext’ for his ‘intrusion’ was put forward by means of a supplication [petition] contained in a ‘certain parchment roll’ that Edward IV’s sons were bastards and incapable of succession, because their father had been precontracted to marry Lady Eleanor Butler [Talbot] before he married Elizabeth Woodville. The children of George of Clarence were also excluded from succession because of their father’s attainder.

Philippe de Commynes

The Crowland Continuator gives us no other details about what debate, discussion, or proof was produced to support the allegation, except to suggest that the petition originated in the North and was written by someone in London.[2] Dominic Mancini, who was living in London at the time, reported that certain ‘corrupted preachers of the divine word’ gave sermons about the illegitimacy of King Edward’s children, and that the duke of Buckingham supported those allegations by declaring the king had been precontracted to a foreign princess.[3] Philippe de Commynes wrote in his ‘Memoirs’ that it was Robert Stillington, bishop of Bath and Wells, who came forward and gave evidence from his personal knowledge about the precontract to Lady Eleanor and its consummation.[4] Ultimately, the Act of Succession known as Titulus Regius was enrolled in January 1484 during Richard III’s only parliament.[5]

Church courts were quite familiar with marital precontract claims and the resulting disinheritance of children, a scenario that seems to have arisen in pre-modern England with surprising regularity even in the lower social classes. Professor R. H. Helmholz detailed the frequency of such claims in his book Marriage Litigation in Medieval England and determined that they out-numbered straightforward divorce cases. The distant date of King Edward’s alleged precontract to Eleanor Talbot, and their inability to testify, although sounding suspicious or unfair to our modern sensibilities, were of no relevance. There were no applicable statutes of limitations, and a precontract claim could be raised after the deaths of the putative spouses. It was not unknown for someone to wait 20, 30 or even 50 years before enforcing a precontract or making a claim that a particular marriage was invalid. ‘This meant that established marriages could be upset by the stalest of [pre-]contracts.’[6] Claims that sought to declare a child illegitimate because of his parents’ invalid marriage were also more commonplace than we often understand, an artifact of the complex system of marriage and consanguinity rules, and the way that marriages could be formed clandestinely with a simple statement of present intent (both parties saying ‘I agree to marry you’ was sufficient in church law).

Church court

While church courts were endowed with the jurisdiction to determine whether a precontract existed or not, or whether someone’s children were illegitimate as a result, they had absolutely no power to determine who inherited their parents’ estate even if – and especially if — he was the potential king of England. By the fifteenth century, English legal practice was especially clear on this concept: the church courts only had jurisdiction to adjudicate who was a legitimate child from a legitimate marriage. Once it determined that the child was born outside a legitimate marriage, then it was left entirely up to the secular arm to determine what he or she would inherit from their parents. This derived from a primitive notion of the separation of church and state, and the idea that the rights of inheritance derived exclusively from feudal law. The Statute of Merton clearly made this point: no bastard child could ever be an heir to his father’s estate as a matter of English feudal law.[7] Therefore, it must be understood that even if the issue of the legitimacy of Edward IV’s children had ever been referred to a church court for determination, it had no power to say who should inherit the crown. That would always be for secular English law to determine.

Which Ecclesiastical Venue?

The first conundrum in 1483 would have been what court or tribunal to refer the matter to. Each bishop had a ‘consistory court’ for the purpose of hearing cases involving marriage and bastardy, and other matters exclusively within church law jurisdiction. Because of the volume of litigation, however, it was impossible for a bishop to attend to this function personally, therefore he appointed an ‘official’ or ‘commissary general’ to act as his representative in adjudicating disputes. In many dioceses, the dean, archdeacon, or chapter would also have their own courts. However, in matters involving elite personages or sensitive political issues, it was not uncommon for the bishop himself to mediate the dispute, as we can see from the bishop of Norwich’s personal involvement in trying to dissolve the scandalous marriage between Margery Paston and Richard Calle in 1469.

The consistory courts were staffed with judges, lawyers (‘proctors’) and barristers (‘advocates’), examiners to conduct witness interrogation, scribes, archivists (‘registrars’), and summoners (‘apparitors’ or ‘bedels’). No one was required to have a law degree, but most had some formal education in canon or civil law, especially the judges. Quite unlike common law English trials, there were no juries and no examination of live witnesses in open court. Instead, judges based their verdicts solely on the review of offered documents and written depositions which contained the answers given by witnesses to questions (‘interrogatories’) put to them by the examiners. Appeals could be taken either to the archbishop of Canterbury or of York, depending upon which Province the case had been filed in, or directly to the Pope via the Roman Curia. The archbishop of Canterbury’s appellate court was called the Court of Arches, located at St Mary-le-Bow Church in London, and was considered the premier ecclesiastical court in England having both original and appellate jurisdiction.

Court of the Common Pleas

Notwithstanding this church court infrastructure, it seems highly unlikely that the 1483 allegation of precontract would have been referred to a bishop’s consistory court or even to the Court of Arches. The matter touched directly on the royal family and on whom would become the next king of England. In looking for past precedents, the closest analogue is the ecclesiastical trial of Eleanor Cobham, wife of Humphrey Duke of Gloucester. Cobham was married to the uncle and heir-presumptive to Henry VI, and was in line to be queen-consort if the king died without children. In the summer of 1441, Cobham was implicated by members of her household in using magic to predict the death of the king. An indictment was brought forward in the King’s Bench against the household servants, and they were charged with sorcery, felony, and treason. Cobham was named as an accessory. While the secular courts had jurisdiction over charges of treason and felony, the church courts had jurisdiction over matters of heresy and witchcraft.

Rather than refer the matter to a bishop’s consistory court, the king’s council selected a group of prelates to act as an ecclesiastical tribunal to determine the truth of the allegations against Cobham and her punishment. No doubt this was done because of the shocking political implications of accusing the heir-presumptive’s wife of treasonable sorcery. The panel included the archbishops of Canterbury and York, the cardinal-bishop of Winchester, the bishop of Bath and Wells, the bishop of Lincoln, the bishop of London, and the bishop of Norwich. Most of these men were also part of the king’s secular government. Bishop Stafford of Bath and Wells was the king’s Chancellor. Cardinal Beaufort of Winchester, Archbishop Kemp of York, and Bishop Alnwick of Lincoln all currently sat on the royal council. Beaufort and Kemp, in particular, were known antagonists and opponents of Gloucester and his wife, and many saw the panel’s work as nothing more than a thinly-veiled attempt to destroy them and their political faction.[8]

Similarly, the political dimensions in 1483 were far too enormous to refer the matter of the princes’ illegitimacy to a single prelate or his court. (And what bishop would have wanted to have sole responsibility to decide such an inflammatory issue?) Therefore, if Cobham’s case is any precedent, it would seem that the only appropriate way to do so would have been for the royal council, of which the Lord Protector was the chief, to summon a group of prelates and men learned in canon law to hear it. And, just like the Cobham case, the membership on that panel could be perceived as having partisan agendas and rendering a biased decision.

How Would a Church Court Conduct the Litigation?

Church court procedure was usually divided into three stages: an opening hearing, the taking of evidence, and the reading of a judgment. The first stage required the party asserting the allegation of precontract to appear in person or by a proctor, in order to recite the specifics of the ‘citation’ or claim. The second stage involved the witnesses being identified by name and sworn in, and then taken outside of court to be interrogated separately and in private according to questions prepared by the parties and the judge. The testimony of each witness would be reduced to a written deposition, and then published (read aloud) on a date set by the judge. At that time, witnesses could be challenged or ‘exceptions’ made to their character or testimony. The last stage was for the judge to read all the depositions and review any documentary evidence, and then arrive at a decision. The parties could argue through their advocates that their side was the correct one, and even submit legal briefs to support their case. The judge was given wide latitude to arrive at whatever conclusion he deemed compliant with substantive canon law. He was not required to explain the reasons supporting his decision, and could proceed to a separate hearing on what punishment was appropriate under church doctrine. From the first hearing to the final judgment, the average lifespan of a typical marriage case was around 5-7 months.[9]

Would an ecclesiastical tribunal have followed this general procedure in 1483, and if so, would we have had the benefit of written depositions from Stillington or any other witnesses who would have testified about the precontract? To the latter question, the short answer is probably no. There exist no witness depositions or transcripts from Eleanor Cobham’s ecclesiastical trial, only the indictment filed against her servants in the King’s Bench records (what we do know about the Cobham trial comes from The Brut, and other London chronicles, not from official court or church records). Nevertheless, her case was generally divided into these three stages. After fleeing to Westminster Abbey for sanctuary, Cobham was cited to appear at St Stephen’s Chapel where she was examined on several points of felony and treason, which she strenuously denied, and was allowed to return to sanctuary. The next day, she was summoned to hear the incriminating testimony of a witness against her; she confessed to some of the charges and was transferred to Leeds Castle in Kent. A secular criminal law investigation was conducted into the three household servants, and it was determined that they – and Cobham — had celebrated a mass using elements of necromancy and sorcery in order to predict the death of Henry VI, an act of treason.

Cobham was next hauled before the ecclesiastical tribunal at St Stephen’s Chapel four months later, for the purpose of sentencing. Archbishop Chichele of Canterbury begged illness from this event, and therefore it was Adam Moleyns, clerk to the royal council, who read the articles of sorcery, necromancy, and treason to her. Cobham again vociferously denied the charges but admitted to using potions to conceive a child with Humphrey. Several days before issuing a sentence, the ecclesiastical panel forcibly divorced Cobham from her husband. What due process was used to work the divorce is not recorded. Certainly, it was not initiated by Humphrey, and under canon law there were no grounds for divorce if one of the spouses fell into heresy.[10] Cobham’s sentencing hearing came a few days later, and she was given the punishment of walking penitent at three public market days. Thenceforth, she never left the king’s strict custody and is believed to have died at Beaumaris, Wales, in 1452, five years after Humphrey.[11]

The Penance of Eleanor Cobham, by Edwin Austin Abbey (1900)

While not a perfect analogue, the Cobham case is instructive as to how a hypothetical ecclesiastical tribunal would have litigated the precontract issue in 1483. It would have had an initial hearing when the charge was announced, then it would have received witness testimony, and then it would have had announced its decision after review of the evidence. Elizabeth Woodville’s presence would not have been required but she could have had a proctor there to represent her interests.[12] Of course, there would have been no jury, and none of the safeguards that juries ostensibly brought to secular litigation. Those sitting on the tribunal would not have heard live testimony nor observed the demeanor of those testifying; they would have relied on recorded depositions. There would have been no requirement for a reasoned opinion describing the rationale for the decision. And there would have been no sentencing hearings, since the only role for this tribunal would have been to answer one question about the precontract’s existence. The matter would then be returned to the secular courts, including Parliament, for further consideration.

What type of evidence would have been received?

One was required to produce documentary evidence and/or witness testimony to substantiate a claim in the church courts. Documentary evidence was almost unheard of in marriage cases, and even it if had been produced, forgery was so common that it was often looked at as being less weighty than oral testimony.[13] If resting solely on witness testimony, then the case could be proven with only two people who were able to testify from direct observation or other reliable information. The ‘two-witness rule’ was formulated in pre-Christian classical Rome as full proof (‘probatio plena’) and was absorbed into church doctrine based on certain passages in the Bible. Hearsay was not excluded. In a 1443 case from the Rochester diocese, for example, the church court allowed the testimony of John North who said that William Gore told him of seeing a marriage contracted between Alice Sanders and John Resoun.[14] Proof of long cohabitation and children being born to a couple were not relevant except to prove sexual intercourse. Beyond that, what sentimental force it had on the judge is hard to say, certainly less than it would today. The validity of a marriage depended on the existence of a marriage contract, not on the birth of children. What was more relevant to church courts were the relative social statuses of the parties involved, as can be seen in a 1419 case where a woman lost her precontract case because the putative husband introduced witnesses to show that he was of a far superior social station.[15]

Since marriage cases often turned exclusively on the testimony of two people, we find paradoxes and difficulties, and cases involving collusion and fraud. Helmholz recounts a case from York where Alice Palmer had married Geoffrey Brown and lived with him for four years. The union was not a happy one as Geoffrey physically abused Alice. As a result, Alice and her father found another young man, Ralph Fuler, and gave him gifts (i.e. bribes) so that he would say that he had contracted marriage with the said Alice before any contract and solemnization of marriage had occurred between Alice and Geoffrey. ‘This stratagem worked. Alice and Geoffrey were divorced. The whole matter came to light only some years later, after Geoffrey had in fact married another girl. Alice then sued to annul the previous judgment and get him back.’[16] Helmholz also recounts coming across a few isolated cases where an affirmative judgment was based on the testimony of a lone witness rather than the two required.[17]

For this reason, John Fortescue wrote about the inanity and corruption of the ‘two-witness rule’, saying that it was clearly inferior to the English common law system which required a jury of 12 good men to attest to the truth of the facts presented by the prosecution. To prove his point, Fortescue used the example of someone entering into a valid clandestine marriage, walking away from that, and then marrying someone else in a public ceremony to which two witnesses could testify in a court, and none to the clandestine marriage. The Roman law requiring two witnesses in this situation, according to Fortescue, would condemn the person to live in perpetual adultery with the second wife.[18] But two witnesses were all that was required in the ecclesiastical courts, and that is all that would have been required in 1483 to prove the precontract, and thus the princes’ illegitimacy.

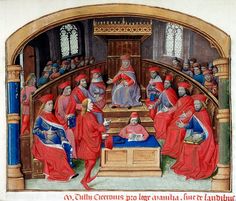

Medieval court in session

If Phillipe de Commynes was accurate, then we already know the identity of one witness: Robert Stillington, bishop of Bath and Wells, and former chancellor to Edward IV. And this is significant because the ‘two-witness rule’ had numerous exceptions. William Durantis, the medieval procedural encyclopedist, managed to elucidate thirty of them. Most were created for situations in which it would be expected and natural for only one witness to observe an event (a father, for instance, testifying that his son had been coerced into becoming a monk was sufficient to prove that fact). Other exceptions rested on the quality of the witness. The testimony or word of the Pope or other high clergyman, for instance, could alone prove a fact in the church courts.[19] In a strict sense, the testimony of a sitting bishop and former Chancellor, coming from a high clergyman about a clandestine marriage that he personally observed, could have fallen into one of these exceptions to the rule and it alone might have been deemed full proof of the precontract.

Aside from the requirement of two witnesses and its exceptions, the church courts applied a somewhat mechanical system for sorting out qualified from unqualified, and believable from unbelievable, testimony. The parties themselves could not testify as they were deemed partial to their side of the case. For the same reason, the parties’ servants, friends, and relatives, were deemed unqualified to testify. Heretics and believers who were in the state of mortal sin could not testify at all. Rank in the nobility or clergy merited a witness superior credit, rich man prevailed over poor, Christian over Jew.[20] Had Bishop Stillington, or another high clergyman, testified in front of an ecclesiastical tribunal in 1483, then his testimony would have been accorded the highest evidentiary weight possible under the rubrics set out by canon law.

But what about the duke of Buckingham and the preachers who were making public statements in 1483 about the princes’ illegitimacy? Could they have testified in a canon court? The answer seems to be in the affirmative. As shown above, the fact that none were present at the time of the precontract would not necessarily bar their testimony since there was no strict rule against hearsay. The problem rests in what they were saying, which suggested different grounds for the princes’ illegitimacy (the duke saying that Edward IV was precontracted to a foreign princess, and the preachers saying it was because Edward IV himself was a bastard). Under canon law, full proof required two witnesses providing the same basic facts, not two different scenarios for invalidating a marriage.

There is also Mancini’s insinuation that the preachers were ‘corrupt’ in some manner, and even a suggestion by Commynes that Stillington had some sort of personal baggage when he was briefly sent to the Tower in 1478. Canon law permitted any witness, even a clergyman, to be impugned and ignored if they were shown to be of bad character. That required proof, too, not mere suspicion, and there was no mechanism to cross-examine witnesses directly. One had to produce evidence, usually in the form of another witness, to show that someone was unqualified. According to Professor Charles Donahue, English church courts were often more lax about this than they should have been. He found several cases in which the court proceeded to sentencing without regard to the fact that the witnesses on the winning side were objectionable. In a precontract case, Cecilia Wright c. John Birkys, Cecilia successfully petitioned for a divorce of John from his current wife, Joanna, on the ground that John had previously promised to marry Cecilia and had had intercourse with her. Cecilia produced only two witnesses, one of servile condition, the other Cecilia’s sister and the wife of the other witness. ‘Probably neither witness was admissible under the academic law. Yet despite uncontradicted testimony as to the status and the witness’s admission of the relationship, Cecilia prevailed in two courts.’[21]

Such cases suggested to Professor Donahue that in English church court practice, there was no automatic bar to the consideration of anyone’s testimony. Indeed, he concluded ‘there is no case of which I am aware in which a party lost because some or all of the witnesses necessary to make up his case proved to be incapable of testifying under canon law’.[22] It has led modern historians to say that the church courts were often deciding marriage cases based on ‘evidence that was seldom sufficiently verified’ and that ‘some judges appear to have bent the law to fit their normal, and sensible, prejudices’.[23]

How conclusive would the decision have been?

Once the ecclesiastical tribunal had decided the issue of the precontract, the matter would be returned to the secular courts to determine whether the children could inherit under English law. A certificate of legitimacy or bastardy coming from the Church could not be challenged in any subsequent lawsuit, even if it involved different parties, facts, or issues.[24] This was the general rule, although Helmholz found cases where English secular judges disobeyed the church court’s decision when it would have worked an inequity or a violation of English law. They were particularly sensitive to church intrusion into matters involving inheritance. In a case from 1337, for example, it was pleaded that the plaintiff was a bastard by reason of birth before his parents’ marriage. The plaintiff countered by showing the record of a bishop’s certificate from a previous decision testifying to his legitimacy. The court, however, refused to accept it as conclusive. As Judge Shareshull said, ‘I cannot have this answer because with it a man would gain inheritance against the law of the land.’[25] Shareshull would later become Edward III’s chief justice in 1350.

St-Mary-le-Bow Church, London, designed by Christopher Wren.

Less certain is whether any appeal could have been made to the Pope. Since the matter ultimately concerned inheritance law and feudal succession to the English throne, it seems unlikely. Certainly, Elizabeth Woodville and her allies did not take up any appeal to the Roman Curia after her sons by Edward IV were declared illegitimate by the three estates. Such an effort, in any case, might have arguably violated the Statutes of Praeminure enacted during the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. They forbade Englishmen and women to pursue in Rome or in the ecclesiastical courts any matter that belonged properly before the king’s courts, including ‘any other things whatsoever which touch the king, against him, his crown and his regality, or his realm’. There were strict penalties for doing so.[26]

Conclusion

The decision not to refer the issue of the princes’ alleged bastardy to a church court will always remain one of the criticisms of how Richard III came to the throne. As shown above, there were serious procedural dilemmas, such as how to properly constitute an authoritative ecclesiastical tribunal and how such a tribunal would have managed the hearing of a politically divisive claim. Even more difficult to predict is whether the church tribunal would have accepted a lowered burden of proof of just one eyewitness’s testimony to the precontract or would have sought out additional witnesses. In the final analysis, these matters of procedure do not dictate the outcome. As long as there was credible proof of the precontract, strict church law would have bastardized the offspring of the bigamous parents. English secular law did not soften this result, and indeed, militated against such children from inheriting their father’s estate. The ultimate question is whether the English public would have found an ecclesiastical tribunal to satisfy their notions of due process, or whether they would have seen it merely as a handmaiden to a political coup d’etat. It seems safe to say that we’d still be debating the merits and propriety of Richard III’s accession to the crown regardless of the juridical mechanisms employed, even if those mechanisms followed the precise letter of canon law.

Related Posts

“Debunking The Myths – How Easy Is It To Fake A Precontract?”

Notes

[1] R. H. Helmholz, “Bastardy Litigation in Medieval England,” American Journal of Legal History, Vol. XIII (1969), pp. 360-383 and R. H. Helmholz, “The Sons of Edward IV: A Canonical Assessment of the Claim that they were Illegitimate,” Richard III Loyalty, Lordship and Law, P.W. Hammond (ed.) (1986).

[2] Nicholas Pronay & John Cox (eds.), The Crowland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486 (Allan Sutton, London, 1986), pp. 158-161.

[3] C. A. J. Armstrong (trans.), The Usurpation of Richard the Third by Dominicus Mancinus (Oxford Univ. Press, 1936), pp. 116-121.

[4] ‘In the end, with the assistance of the bishop of Bath, who had previously been King Edward’s Chancellor before being dismissed and imprisoned (although he still received his money), on his release the duke carried out the deed which you shall hear described in a moment. This bishop revealed to the duke of Gloucester that King Edward, being very enamoured of a certain English lady, promised to marry her, provided that he could sleep with her first, and she consented. The bishop said that he had married them when only he and they were present. He was a courtier so he did not disclose this fact but helped to keep the lady quiet and things remained like this for a while. Later King Edward fell in love again and married the daughter of an English knight, Lord Rivers. She was a widow with two sons.’ Michael Jones (trans. & ed.), Philippe de Commynes “Memoirs”, 1461-83 (Penguin Books, 1972), pp. 353-54.

[5] Rosemary Horrox (ed.), The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England 1275-1504, Vol. XV Richard III 1484-85 (Boydell, London, 2005), pp. 13-18.

[6] There was no preference by canon law courts favoring the ‘settled’ or ‘long-standing’ marriage over the mere contract by words. R. H. Helmholz, Marriage Litigation in Medieval England (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1974), pp. 57-59, 62-64.

[7] Helmholz, Bastardy Litigation, pp. 381-383. The Statute of Merton was passed during Henry III’s reign in 1235, and provided in part, that ‘He is a bastard that is born before the marriage of his parents’. The parents’ subsequent marriage did not alter the status of bastardy.

[8] Ralph A. Griffiths, “The Trial of Eleanor Cobham: An Episode in the Fall of Duke Humphrey of Gloucester”, King and Country: England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century (Hambledon, London, 1991), pp. 233-252.

[9] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 124-140, 113-115.

[10] Pierre Payer (trans.), Raymond of Penyafort’s Summa on Marriage (Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2005), pp. 53, 80-81. In Title X, Dissimilar Religion, Penyafort states that when believers contract marriage between themselves and afterwards one falls into heresy or the error of unbelief, the one who is abandoned cannot remarry.

[11] Griffiths, Eleanor Cobham’s trial.

[12]Brian Woodcock, Medieval Ecclesiastical Courts in the Diocese of Canterbury (London, 1952), pp. 83-85.

[13]James A. Brundage, Medieval Canon Law (Longmans, London, 1995), pp. 132-133.

[14] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 131-132.

[15] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 132-133.

[16] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, p. 162.

[17] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 228-232.

[18] Shelly Lockwood (ed.), Sir John Fortescue: On the Laws and Governance of England (Cambridge Univ Press, 1997).

[19] R. H. Helmholz, “The Trial of Thomas More and the Law of Nature”, http://www.thomasmorestudies.org/ tmstudies/Helmholz2008.pdf [7/3/08], pp 9-10, FN 31.

[20] Mauro Cappelletti & Joseph M. Perillo, Civil Procedure in Italy (Columbia Univ., 1965), pp. 34-35, footnote 139 cites the Decretals of Gregory IX, Liber Extra, title XX de testibus et attestationabus, cap. XXVIII.

[21]Charles Donahue, Jr., “Proof by Witnesses in the Church Courts of Medieval England: An Imperfect Reception of the Learned Law”, in Morris S. Arnold, Thomas A. Green, Sally Scully, and Stephen White, ed., On the Laws and Customs of England: Essays in Honor of Samuel E. Thorne (North Carolina Univ. Press, 1981), pp. 127–154 and p. 147, footnote 89, citing case from York, Borthwick Institute, CP.E. 103, 1367-69.

[22] Donahue, Proof by Witnesses, p. 147. It should be noted that Donahue’s research focused on the 13th and 14th centuries, but Helmholz’s research did not reveal any different trends in the 15th century.

[23] Helmholz, Marriage Litigation, pp. 61-62, citing Lacy, Marriage in Church & State, and p. 66.

[24] Helmholz, Bastardy Litigation, p. 373.

[25] Helmholz, Bastardy Litigation, p. 374.

[26] 27 Edw.III st. 1, c. 1, 38 Edw. III st. 2, cc. 1-4, 16 Rich.II c. 5. Richard Burn, Ecclesiastical Law, Vol. II (9th ed., 1842) pp. 37-39.

Pingback: Debunking The Myths – How Easy Is It To Fake A Precontract? | RICARDIAN LOONS

Reblogged this on murreyandblue.

LikeLike

Good article. But I nitpick a little:

1. Clarence had only one son still living in 1483-Edward (there was a daughter, Margaret);

2. Humphrey of Gloucester was, I recall, heir-presumptive to Henry VI,not heir-apparent.

I view the story of Stillington as performer of marriage ceremony to Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot Butler, or witness to the actual precontract promise, with scepticism. I’m sure that in either circumstance, he would have been made to testify to such in formal setting; including the synod Annette Carson notes happened in Richard III’s reign.

I suspect Stillington had some other source of information about the precontract. It was good enough to convince him (remember he did not retract the story after Bosworth, despite harsh treatment by Henry VII), but probably not regarded by Richard III and his advisors to be convincing to the public.

LikeLike

Thank you for the feedback. I am going to edit the essay to change “heir-apparent” to “heir-presumptive” and “sons” to “son”. I have heard of the skepticism about Stillington. But I felt those lines of argument fell well outside the scope of my piece, which is more about the procedural (boring) stuff. I agree with you that Richard may have felt the evidence was too shaky to convince the public. And even if it was “strong”, I have a feeling that there would have been a large public outcry against the church trial in any event. As we see from Eleanor Cobham’s trial, Henry VI did not endear himself to the realm by employing that device.

LikeLike

If you want to know how easy it was, please take a look at the article by Shannon McSheffrey of Concordia University Montreal entitled ‘Detective Fiction in the Archives.; – available online- which is about a series of cases brought before the Consistory Court of the Diocese of London between 1469-74

What were the cases all about – bigamy arising from a long ago but only just just remembered pre-contract – very common in the Middle Ages.

But what would be the situation if it turns out in the case of the pre-contract couple there was an impediment (canon law diriment impediment) such as being in the Prohibited Degrees of KInship ?

LikeLike

Thank you, latrodecta, for providing a citation to McSheffrey’s article, which I will certainly read. To answer your last question, the first marriage contract (the “pre-contract”) would have to comply with canon law on prohibited degrees of kinship, and if someone came forward to claim the precontract was defective based on prohibited degree of relationship, they’d have to present proof via the family genealogical trees of each partner. If I recall correctly, some degrees of kinship could be papally dispensed ex post facto, after the date of the precontract. Obviously, if you were rich and powerful enough to send an advocate to the Papal curia, the chances of getting that papal dispensation would be significantly better than someone of a lower station. I didn’t look into that particular scenario in regards to the Edward IV-Eleanor Talbot precontract, as I’m not aware of any claim that their union presented one within the prohibited degrees.

LikeLike

Hi White Lily

Thank you for your reply. I found that article when I was researching bigamy and I didn’t just research I asked around and as far as I could ascertain the situation is the same now as then any claim made on bigamy has to be decided by a Court. One of the modern cases I picked up on involved a Mafia Capo widow whose relatives claimed she had been married before, but the marriage had not been dissolved. Yes she had been married before but because it had happened in the UK, the ruling had to come from a UK Court. What was the ruling?. 1st marriage null and void because of the impediment known as coercion – it’s also an impediment under canon law. As it is it would seem that the Court mentioned in the article would have been the same one to which Richard would or should have submitted his claim, the same one that had already picked up on evidence of perjury and bribery. I can just hear the judges now. ‘Oh, we’ve heard the one before’

The reason I asked about Prohibited Degrees of Kinship was because they were related, 3rd degree consanguinity, 3rd degree affinity and they because of one of the biggest hang-ups of the Medieval Church, incest, picked from that 800page German tome, were the two worst impediments. Under canon law at the time, their relationship would have been regarded as incestuous. It was a very rigidly enforced doctrine and not only included 1st, 2nd, and 3rd cousins, but their half, step and adopted siblings as well – Eleanor was the half-sister of second cousins (3rd degree consanguinity). Corroboration can be found in the dispensation granted for the marriage of his son and her niece – the relationship between her sister and Edward would have been the same. Put it this way, no dispensation no validity. I even picked up on a case where the bridegroom had to obtain a dispensation because he’d already slept with his future mother-in-law – that’s how rigidly it was enforced.

And boy do I know about diriment impediments thanks to marrying a Catholic, another being Disparity of Cult – If I had ‘t already been baptized we would have needed a dispensation for that. Not only that but we were asked – this was before the Catholic Church changed the rules – if we were related. And guess who was one of the last to obtain an annulment because of failure to obtain a dispensation – Rudy Giuliani -3rd degree consanguinity.

But the real factor for me is whether Eleanor had changed her marital status. As a lawyer you must know the situation before 1870 and the legal terms feme covert and feme sole – I’m not a lawyer but I have studied Law. According to still extant legal documentation, picked up through of all people, John Ashdown Hill, she didn’t. On one of the documents dated 4th June 1468 – she died on the 30th – she’s actually described as a widow -Alianore Boteler, wyf of Sir Thomas Boteler (deceased) – in other words still feme sole.

According to JAH – corroborated – Eleanor went on to become a Carmelite tertiary, a tertiary being very popular with medieval women as it gave them the best of both worlds, being able to remain at home while still being an official religieuse. According to the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland by the fifteenth century only femes sole could become tertiaries and the Carmelites didn‘t change their rules until 1474. If she’d taken all three vows that in itself would have constituted a diriment impediment. According to John Witte (From Sacrament to Contract) if one of the parties went religious, that automatically cancelled the contract and Eleanor became a tertiary before Edward married Elizabeth Wydeviile.

That 800 page tome is Inzestverbot und Gesetzgebung – Konstuktion eines Verbrechens (Incest Prohibition and Legislation – Development of a Crime (Karl Ubl) – it was actually a crime and when I say hang-up that would appear to be something of an understatement.

Finally the Titulus Regius – it reads like something Goebbels might have come up with – 90% propaganda with the allegation of bigamy coming way down. Given the other allegations – one party was still alive at the time – I wonder what Carter Ruck would make of it. As it is while libel didn’t really take off until James 1 civil proceedings had been happening since the reign of Edward 1

The Ricardians would still argue that all that notwithstanding Edward’s marriage would still have been invalid because of the secrecy and no banns. Unfortunately for them some time in the 14th century the Church had already come up with the means to allow secrecy and no notice being necessary – the marriage licence, either the common or special licence -and still available today

Some further thoughts re the Curia. Firstly, the marriage between Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon agreed in 1489. Given Henry VII’s still shaky hold on the throne would Isabella and Ferdinand have agreed if they had reason to believe that neither Henry or Elizabeth were legit? For aught anyone knows they could have made ‘backdoor’ enquiries. Secondly the first papal dispensation for the marriage of Henry and Elizabeth was granted on 27th March 1484, the first of three. Like the Curia did ‘t know what the situation in England was at the time? Thirdly the Wydevilles through Jacquette’s maternal grandmother were related to the Orsini family, the biggest, most important, and most influential family in Rome, Popes, Cardinals, Bishops and Vicar-Generals and very much big noises in the Curia at the time. One wonders if the Orsini had become involved in the scheme of things as one can’t see that first dispensation being granted without someone high up pulling strings.

Last but not least Elizabeth could have had help another way, Owen Tudor the monk uncle about whom so little is known but certainly was in situ during both times in sanctuary and if Elizabeth didn‘t know him what about grandmother Jacquette? He certainly couldn’t have been completely unknown if like his brothers he received an annuity from Henry VI in 1452 and rather curious that his nephew had him buried not in the communal cemetery, the other side of the Chapter House, but St Blaise’s Chapel, reserved for Abbots, as his memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey attests and paid all the funeral costs. And what was that £2 worth 1K today paid in 1498 all about? And when did Henry discover about his monk uncle? It’s long been the assertion that the couple never met before Bosworth, but given that in the autumn of 1470 they were living next door to each other, Uncle Owen and a secret way into the Abbey, handy for any royal in immediate need of sanctuary, who knows? So move over Philippa – Latrodecta is now spinning her web.

LikeLike

Wow, that’s a very detailed comment, almost a blog post itself!, but thanks for sharing your thoughts and good luck with your research. I have tried to keep this post limited to church court procedures in marital cases, because once people start arguing about the preponderance of evidence, the hidden intentions of people who lived hundreds of years ago, or the substantive canon law, things tend to go in circles.

So, to keep to the procedural aspects of church litigation, I would make the following observations:

First, a church court would have required Elizabeth Woodville (or her proctor) to produce 2 witnesses to prove her clandestine marriage to Edward IV. It was once believed that her mother, Jaquetta, had attended that ceremony, but this has been debunked by non-Ricardian scholars and historians as being unsubstantiated legend. Moreover, under church court procedures, Jaquetta would have been unqualified as a witness to testify since she was related by blood and deemed to be biased. (Plus, she was dead by 1483.) I’m aware of no other witnesses that could have been called, except some unnamed boy choristers and a priest, the identities of the former being unknown, and the identity of the priest believed to be someone who died not long after performing the ceremony. This would have put Elizabeth Woodville in the position of having no proof. This is why clandestine marriages were frowned upon, and why priests performing those marriages were subject to steep penalties, including excommunication, monetary penalties, and loss of their benefice.

Second, if Elizabeth Woodville (or her proctor) had come forward with an argument that Edward IV did not have a valid marriage with Eleanor Talbot because they were within the diriment (nullifying) impediment of consanguinity, she’d have to produce the proper genealogical evidence. Unfortunately, this would have gone nowhere because there is no evidence that Eleanor and Edward shared a common ancestor or “stock” up to the level of great-great-grandparent. I would note that non-Ricardian historians like MA Hicks and Richard Helmholz, who have gone over this historical terrain repeatedly for the past 30 years, have never identified such an obvious nullifying impediment to the alleged Edward IV-Talbot marriage.

Third, if Elizabeth Woodville (or her proctor) had argued that the Talbot marriage was within the prohibited degree of affinity by virtue of some of their relatives intermarrying, she’d have to produce evidence as to precisely what that affinity was between Edward and Eleanor. Moreover, she’d have to overcome the Fourth Lateran (1215)’s decree that “affinity does not beget affinity” and procedurally face the consequences of making that very argument. For, if she were to make that argument, then her own marriage to Edward IV was within the fourth degree of affinity since she and Edward IV shared a common great-great-grandfather: Edward III. The “affinity” was created by Jaquetta’s marriage to John duke of Bedford, that king’s great-grandson and cousin to Edward earl of Cambridge, Edward IV’s grandfather. (Woodville and Edward IV had never obtained any dispensations from Rome, as far as I’m aware.) Moreover, prohibitory impediments of affinity did not invalidate marriage contracts and could be papally dispensed even after the parties had died.

Finally, and forgive me for getting a little bit into substantive canon law, while incest was taken very seriously by pious Christian folks, as you correctly point out, the church was – shall we say – a bit malleable on the subject. We see this on the Iberian peninsula, with uncles marrying nieces as a matter of tradition and custom, and no one would argue now (nor, argued then) that they were bad Christians, or horrific unnatural monsters, in the context of their period. It was church tradition to honor local customs, which is why popes over the late medieval period repeatedly “forbade” clandestine marriages, but realized that in some countries they were part of the local custom. England ultimately took a hard-line on clandestine marriages, and in the centuries following the fifteenth required the recording of marriages in parish church records. As my blogging partner Blood of Cherries has shown in her post about Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, even that autocratic Tudor king found proving her precontract to the earl of Northumberland to be too burdensome to insist on, and therefore proceeded on other legal grounds to prove her treason.

Going forward, I respectfully ask that we refrain from any comparison between 15th century parliamentary acts like Titulus Regius and Josef Goebbels’ hideous propaganda campaign to de-humanize large segments of the German people. I’ll assume you were probably being tongue-in-cheek, but it has the effect of minimizing the true horror of those 20th century events, and exaggerating those that occurred in the 15th. Elizabeth Woodville was allowed to live out her days in decency, her eldest daughter was invited to become a prominent figure in Richard III’s court, and her welfare was being looked after by the king’s attempt to marry her into continental royalty. Let’s not descend into the all-too-common tendency to make inflammatory comparisons on the internet. In fact, to quote the very article by Professor McSheffery that you cited in your comment above, I prefer this scholar’s calm, even-tempered approach to interpreting the Stockton v. Turnaunt divorce case, where she admits to having her own idiosyncratic, privileged assumptions that could cloud her best judgment:

“Yet crucially important aspects of the past remain occluded, and it is hard to see how they can be reached through empirical methods. It is comparatively easy to hypothesize about how medieval documents functioned when they were wielded in rational ways that maximized the economic, political, or social self-interest of the wielders. What remains less easy to infer are actions motivated by unreason or emotion, or by a different kind of self-interest that cannot be measured by economic or political advantage. My thinking about the Turnaunt case has privileged scholars’ arguments about the greater legal and political savoir-faire manhood conferred as well as assumptions about Richard’s self-interest – the aristocrat’s need for a male heir, his desire (only to be expected in his circumstances) to rid himself of a wife who was barren and possibly even absent. Still remaining veiled, accessible only through speculation, are the reasons for the marriage’s breakdown and Joan’s disappearance: Joan may have descended into serious mental illness, or Richard may have been physically or mentally abusive, or they may simply have intensely disliked one another. But perhaps I am wrong that Richard manipulated the case. If Joan did indeed voluntarily bring the suit herself, as the records state, she used litigation not to advance socially, politically, or economically, as did many other late medieval litigants, but in fact to fall quite precipitously out of a marriage with a gentleman, into a life cut off from her marital and natal families. It may have been worth it to her to be free of the marriage, for reasons that may, or may not, have been rational, even though divorcing Richard evidently meant losing both her daughter and her own birth family. Either way, Joan’s case highlights one of the difficulties facing us as historians, for we often depend, sometimes unconsciously, upon our assumptions about rational strategies of social negotiation to make narrative connections between the scattered bits of evidence out of which we write our history. The end of Joan’s life, as far as I know, is not documented, leaving us only with speculative imaginings. It is hard to imagine, however, that her days ended happily.”

LikeLike

Why you think my username is Latrodecta?

And why have I nothing but contempt for the legal profession who’ve had to learn the hard way the truth behind Proverbial 16.18?

LikeLike

Hi Latrodecta,

A lot here!

Sorry to be dense, but could you possibly explain more specifically what you mean by Eleanor being the half-sister of second cousins? To Edward? Could you walk me through the steps if it’s not too much trouble?

M

LikeLike

It is common for less informed people to confuse Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, with his father-in-law Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick and to believe that marrying someone made the members of your family related to the members of theirs. This is not the case, as this article and Barnfield, which it cites, have shown:

https://murreyandblue.wordpress.com/2015/08/01/to-avoid-any-confusion/

Edward IV and Lady Eleanor Talbot were, therefore, not related in blood within the prohibited degrees. This can be illustrated if necessary.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Am I to understand from your comment that you think that I’m less well informed than you.?

As one of my former colleagues termed me ‘ the researcher from hell’.

For the record how good is your knowledge of the following:

Latin/Greek

Medieval languages

Celtic (, Brezhoneg,Kernow,, Gaelige, Garlic, Cymraeg)

LikeLike

Sorry typo. Garlic should read Gaelic

LikeLike

On this matter, certainly.

If Lady Eleanor and Edward IV required a consanguinity dispensation for their 1461 marriage, then they needed a common blood ancestor within the fourth degree or lower, as defined by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. No such person exists and their most recent common blood ancestor would be Edward I, in the sixth degree.

If you altered the contemperaneous canon law, such that the Beauchamp-Neville marriage made the bride’s family related to the groom’s family and so on, which came before 1461, Jacquette’s marriages to the Duke of Bedford and then Sir Richard Woodville would preclude her daughter from marrying Edward IV without a consanguinity dispensation.

So Edward IV was either a bigamist, under the real law, or a lifelong bachelor, to follow your parallel universe. Either way, he could have no legitimate children by Lady Grey.

PS Brevity is the soul of wit.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Latrodecta,

I’m afraid Stephen is actually right here.

Before you ask, I read Medieval Latin (how are your palaeography skills?), have French, Spanish, a bit of Italian, a fair bit of the old Gaeilge (my mother came from a Gaeltacht area), a smattering of Welsh, have studied Old and Middle English, briefly dabbled with Breton and am currently learning Japanese .

All completely and utterly irrelevant to the subject in hand, of course.

More relevantly, I’ve been studying late medieval canon law relating to marriage on and off for 14 years.

All will be explained in proper detail in due course,

LikeLike

In reply to latrodecta:

Wow, that’s a very detailed comment, almost a blog post itself!, but thanks for sharing your thoughts and good luck with your research. I have tried to keep this post limited to church court procedures in marital cases, because once people start arguing about the preponderance of evidence, the hidden intentions of people who lived hundreds of years ago, or the substantive canon law, things tend to go in circles.

So, to keep to the procedural aspects of church litigation, I would make the following observations:

First, a church court would have required Elizabeth Woodville (or her proctor) to produce 2 witnesses to prove her clandestine marriage to Edward IV. It was once believed that her mother, Jaquetta, had attended that ceremony, but this has been debunked by non-Ricardian scholars and historians as being unsubstantiated legend. Moreover, under church court procedures, Jaquetta would have been unqualified as a witness to testify since she was related by blood and deemed to be biased. (Plus, she was dead by 1483.) I’m aware of no other witnesses that could have been called, except some unnamed boy choristers and a priest, the identities of the former being unknown, and the identity of the priest believed to be someone who died not long after performing the ceremony. This would have put Elizabeth Woodville in the position of having no proof. This is why clandestine marriages were frowned upon, and why priests performing those marriages were subject to steep penalties, including excommunication, monetary penalties, and loss of their benefice.

Second, if Elizabeth Woodville (or her proctor) had come forward with an argument that Edward IV did not have a valid marriage with Eleanor Talbot because they were within the diriment (nullifying) impediment of consanguinity, she’d have to produce the proper genealogical evidence. Unfortunately, this would have gone nowhere because there is no evidence that Eleanor and Edward shared a common ancestor or “stock” up to the level of great-great-grandparent. I would note that non-Ricardian historians like MA Hicks and Richard Helmholz, who have gone over this historical terrain repeatedly for the past 30 years, have never identified such an obvious nullifying impediment to the alleged Edward IV-Talbot marriage.

Third, if Elizabeth Woodville (or her proctor) had argued that the Talbot marriage was within the prohibited degree of affinity by virtue of some of their relatives intermarrying, she’d have to produce evidence as to precisely what that affinity was between Edward and Eleanor. Moreover, she’d have to overcome the Fourth Lateran (1215)’s decree that “affinity does not beget affinity” and procedurally face the consequences of making that very argument. For, if she were to make that argument, then her own marriage to Edward IV was within the fourth degree of affinity since she and Edward IV shared a common great-great-grandfather: Edward III. The “affinity” was created by Jaquetta’s marriage to John duke of Bedford, that king’s great-grandson and cousin to Edward earl of Cambridge, Edward IV’s grandfather. (Woodville and Edward IV had never obtained any dispensations from Rome, as far as I’m aware.) Moreover, prohibitory impediments of affinity did not invalidate marriage contracts and could be papally dispensed even after the parties had died.

Finally, and forgive me for getting a little bit into substantive canon law, while incest was taken very seriously by pious Christian folks, as you correctly point out, the church was – shall we say – a bit malleable on the subject. We see this on the Iberian peninsula, with uncles marrying nieces as a matter of tradition and custom, and no one would argue now (nor, argued then) that they were bad Christians, or horrific unnatural monsters, in the context of their period. It was church tradition to honor local customs, which is why popes over the late medieval period repeatedly “forbade” clandestine marriages, but realized that in some countries they were part of the local custom. England ultimately took a hard-line on clandestine marriages, and in the centuries following the fifteenth required the recording of marriages in parish church records. As my blogging partner Blood of Cherries has shown in her post about Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, even that autocratic Tudor king found proving her precontract to the earl of Northumberland to be too burdensome to insist on, and therefore proceeded on other legal grounds to prove her treason.

Going forward, I respectfully ask that we refrain from any comparison between 15th century parliamentary acts like Titulus Regius and Josef Goebbels’ hideous propaganda campaign to de-humanize large segments of the German people. I’ll assume you were probably being tongue-in-cheek, but it has the effect of minimizing the true horror of those 20th century events, and exaggerating those that occurred in the 15th. Elizabeth Woodville was allowed to live out her days in decency, her eldest daughter was invited to become a prominent figure in Richard III’s court, and her welfare was being looked after by the king’s attempt to marry her into continental royalty. Let’s not descend into the all-too-common tendency to make inflammatory comparisons on the internet. In fact, to quote the very article by Professor McSheffery that you cited in your comment above, I prefer this scholar’s calm, even-tempered approach to interpreting the Stockton v. Turnaunt divorce case, where she admits to having her own idiosyncratic, privileged assumptions that could cloud her best judgment:

“Yet crucially important aspects of the past remain occluded, and it is hard to see how they can be reached through empirical methods. It is comparatively easy to hypothesize about how medieval documents functioned when they were wielded in rational ways that maximized the economic, political, or social self-interest of the wielders. What remains less easy to infer are actions motivated by unreason or emotion, or by a different kind of self-interest that cannot be measured by economic or political advantage. My thinking about the Turnaunt case has privileged scholars’ arguments about the greater legal and political savoir-faire manhood conferred as well as assumptions about Richard’s self-interest – the aristocrat’s need for a male heir, his desire (only to be expected in his circumstances) to rid himself of a wife who was barren and possibly even absent. Still remaining veiled, accessible only through speculation, are the reasons for the marriage’s breakdown and Joan’s disappearance: Joan may have descended into serious mental illness, or Richard may have been physically or mentally abusive, or they may simply have intensely disliked one another. But perhaps I am wrong that Richard manipulated the case. If Joan did indeed voluntarily bring the suit herself, as the records state, she used litigation not to advance socially, politically, or economically, as did many other late medieval litigants, but in fact to fall quite precipitously out of a marriage with a gentleman, into a life cut off from her marital and natal families. It may have been worth it to her to be free of the marriage, for reasons that may, or may not, have been rational, even though divorcing Richard evidently meant losing both her daughter and her own birth family. Either way, Joan’s case highlights one of the difficulties facing us as historians, for we often depend, sometimes unconsciously, upon our assumptions about rational strategies of social negotiation to make narrative connections between the scattered bits of evidence out of which we write our history. The end of Joan’s life, as far as I know, is not documented, leaving us only with speculative imaginings. It is hard to imagine, however, that her days ended happily.”

LikeLike

Not just the researcher from hell but the plaintiff too.

When#i meet a lawyer prepared to meet me in.Court I’ll let you know

Ever heard of unprofessional and unethical conduct a matter on which a certain William Catesby thought he could get away with?

Spare me anymore of the legal drivel. It’s getting boring as well as predictable

LikeLike

When you use words like “legal drivel”, make claims that you have refused to explain or support, and then plump yourself up as a force to be contended with, it sounds an awful lot like we are dealing with a modern-day troll. We here at Ricardian Loons don’t deal well with trolling behavior or trolling debate, so perhaps it would be best if you moved along to another blog where you might find a more receptive audience. For now, I thank you for reading the Ricardian Loons blog, but I do need to ask you to refrain from making ad hominem and irrelevant comments. Sorry if that sounds harsh, but life is too short to deal with inanities.

LikeLike

In respect of the Iberians vive la vida loca?

And if the Catholic Church had dispensed with affinity i215 why would they want to know about it 1980?

LikeLike

Superblue

Pity you lack both brevity and wit.

And obviously not enough wit to known about something called the Papal Register Or the canonical computation prior to 1983.

Would you also like to know why Anne Beajuchamp’s inheritance of her father’s estate would not happen today?

LikeLike

Superblue

So where’s your current residence? Cloud Cuckoo Land?

Sumer is icumen in Lhude sing cuccu

As for your singing cacophonic

All sound and fury signifying nothing

LikeLike

So where is the answer to the question I asked twice – Lady Eleanor and Edward IV’s common blood ancestor in the fourth or lower degree?

Sadly, while I make serious historical points based on research, it looks as if you seek to conceal yourself in your own ink, like the cuttlefish

LikeLiked by 2 people

Did you somehow miss the information about half,step and adopted siblings,?

Do research like where? The local Spoonies? Mine includes both the British and Bodleian libraries and I have the Reader’s Pass to prove it

And how good is your Latin? Bodley 73 is only available in Latin

PS

Why don’t you read my article The History Files Medieval Britain and how the NHS came to the rescue of# EdwardIV 6 years ago?

LikeLike

Why wouldn’t Anne Beauchamp inherit from her father today?

LikeLike

I had a word with HOL, According to them any peerage that can descend through the female line – in Scotland it’s automatic – goes to the eldest daughter or her descendants, failing that the second born. Anne Beauchamp was in fact the youngest while the eldest was Margaret who co-incidentally was the mother of Eleanor Butler aka Alianore Boteler nee Talbot whose half siblings – mother Maud Neville – were 2nd cousins of Edward IV..

What happened I can only describe as legal sleight of hand. Anne was a half sibling of Margaret but full sibling of Richard de Beauchamp’s only son who died not long after his father but not before marrying another Cecily Neville, sister of Warwick. It was finally decided after a bitter dispute that Anne should inherit because she was the only full blooded sibling of the deceased heir but I can assure you that wouldn ‘t happen today. It’s the first born daughter, irrespective of whether she’s a full or half sibling of a deceased heir. Interestingly Warwick’s father Salisbury gained his title and all that went with it by marriage

The Wydevilles have taken a lot of stick for being rapacious and ambitious but believe you me the Nevilles put them in the shade. Just study who Ralph Neville married his children off to, Ralph who if he hadn ‘t got his title Earl of Westmorland in 1398 might never have got it it at all owing to the fact that the following year Henry IV took over and he had a thing about his Beaufort half-siblings – Ralph’s second wife was Joan Beaufort. And who were the Nevilles before 1398? Just Barons.

Fnally here’s a little morsel to chew on . What must have Warwick thought when he discovered his cousin’s latest paramour was none other than the daughter of his disgruntled sister-in -law? Who then through his Bishop brother sabotaged the relationship by evoking canon law? And why if Eleanor was married to Edward, didn’t she tell her mother – according to John Ashdown-Hill the whole family knew? What a handy weapon to use against her brother-in-law. And if Bishop Stillington knew anything why didn’t he tell Warwick? What had he to fear given the enormous protection and patronage that both Warwick and his Archbishop brother would have undoubted provided? If Stillington had, wouldn’t that have given Warwick the opportunity to chuck Edward off and put George on and then marry his daughter Isabel to George, with the happy thought that the next King of England would be his grandson which has to be considered when one considers his other daughter’s marriage to Prince Edward of Lancaster? If I ever get to write about the Nevilles, muck-raking would be an understatement!

As for the comment on my research – oh dear. Most of my life has been spent in multi-lingual (includes Latin, Greek, Medieval German,French +Italian.and 5 of the 7 still extant Celtic languages – Galician being the 7th) research added to which Professor Karl Ubl, author of that 800 page tome on incest prohibition, and I share the same Alma Mater. – University of Vienna.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for the information on Anne Beauchamp. It would be interesting to know how those deals were made. From what I can see in the laws of inheritance then, you are quite correct that her sister should have inherited.

I’m not so sure that Warwick the Kingmaker had any idea about the precontract. It seems to have been a complete surprise in 1483.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It wasn’t sleight of hand but Exclusion of the Half Blood. The earldom had first passed to Earl Richard Beauchamp s only son, Henry, who was a child of the second marriage (and then briefly to his daughter Anne, who died). This the earldom had already bypassed the issue of the first marriage so the elder half sisters had no legal claim.

Are you not a lawyer?

Don’t take my word for it. There is a whole chapter on it in Storey’s ‘End of the House of Lancaster’.

There are other issues with other properties of the Earl’s though, some of which had been settled in his lifetime in various ways, for which you would need to refer to Hicks’ ‘The Warwick Inheritance’. Hicks us unfortunately not clear about the simple issue of the Half blood effect on the inheritance of the earldom. He’s often shaky on claims regarding inheritance law.

LikeLike

Thank you, Richard for your response.

Perhaps I did ‘t make my point clear enough. Why wasn’t Warwick not or apparently not informed about that pre-contract? Or more to the point why did Stillington keep silent or for that matter anyone else in the know? For a senior Bishop this would have constituted a very serious dereliction of duty, particularly if he at the same time had not reported a couple having an adulterous relationship and one that went on for nearly twenty years .And why at that all- important Council meeting on May 10th 1483, did he not declare it then? Why nearly another two months?

It also seems that the first attempt was not to question the illegitimacy of Edward V but his father Edward IV, already attempted by Warwick way back in 1469 and King Louis of France dismissing him as ‘Monsieur Blaybourne’. There is some contemporary evidence to suggest that Proud Cis was at odds with her son at the time and wouldn’t have kindly to any suggestion that cast aspirations on her virtue. As I said in my article looking at this allegation of illegitimacy, not only did Cecily uphold the legitimacy of Edward IV in her will but left all mention of Richard out. Ricardians would argue that was to keep Henry VII sweet but as somebody once sang ‘‘It ain’t necessarily so.’

Another who can’t be left out of this equation is Hastings, the only one to be executed after that all tempestuous meeting on June 13th 1483 and again a rephrasing of the question ‘Why were the others spared and not he’, especially Stanley? If they were all conspiring against Richard, they were as a modern maxim has it. ‘all in it together’. What is the one thing that put Hastings apart from the others? His intimate knowledge of Edward’s amatory secrets. And why until now has nobody considered the possibility that he was put out of the way because he knew too much for his own good, that-pre-contract story not surfacing until after his death?

Then there’s the information provided by both Sharon McSheffrey and Richard Helmholz that pre-contract was regularly used to annul marriages on the grounds of bigamy but again why has nobody, apparently, appreciated that Richard used exactly the same modus operandi?

Last but not least Edward himself. Are we to seriously believe that his hormones were so a-jumble that he either forgot or ignored the fact that he was already married to someone else and in the presence of a senior Bishop? What in the certain knowledge that this marriage was going to cause his right hand man,, who already had cause or thought he had to detest the Wydevilles who given events in 1459 would have only been too happy to see him in the loser’s corner, to go ballistic? Furthermore, he was about to set up a new dynasty but in order for that dynasty to be legit, his marriage had to be legit too.

If there’s one thing that does annoy me is historians picking up on mysteries but not investigating them further or not picking up on a mystery at all, Owen Tudor the monk being a case in point so here are some other cases to consider.

The death of Margaret Beaufort

Died on 29th June 1509 in Cheneygates, Abbey of Westminster, where Edward V was born or put another way within 24 hours of ceasing to be Regent and in the biggest sanctuary in England with a handy back door entrance to the Palace. So what was she doing there given the coronation festivities were still ongoing? Taking a well-deserve respite from her labours of the previous two months? Feeling a need to chill out away from those in the Palace? And why die there in the cramped conditions so in contrast with those of the Palace or Coldharbour House which latter would have been a much more comfortable place to chill out away from others and only a short boat journey away? And what brought on this sudden death and why no return to the Palace which could have been easily done in a litter? If one looks at the reconstruction of the Westminster site in Adam Fox’s ‘Pictorial History of Westminster Abbey’ available on the Internet, no problemo. Had she and her grandson fallen out and if so over what? Whatever as Alice might say, given the date and place ‘curiouser and curiouser’.

The death of Edward IV

Various theories on this one but the one that caught my attention was that of Winston Churchill, since adopted by others, appendicitis – tell me about it. So what’s so special about appendicitis? The fact that the symptoms mirror those of aconite poisoning, easily available from the flower known as monkshood – it’s one of the titles in the ‘Cadfael’ series – and still available today in some forms of medication or homeopathic medicine. You can even buy it in Holland and Barrett though I’m not sure about one of its nicknames ‘kiddies calmer’ – overdose and they’ll be calm all right – for good. As for whodunit, cue in that old Roman adage CUI BONO?

Elizabeth Wydeville and Richard III

Again much speculation as to why Elizabeth gave in to Richard in March 1484 and left sanctuary over which much spluttering including Paul Murray Kendall and various reasons submitted but again something seems to have been overlooked, those excluded from sanctuary such as Jews, heretics, apostates and witches ,witchcraft being considered a form of heresy and the fact that in the Titulus Regius Elizabeth was publicly branded a witch. By March 1484 Henry Tudor was becoming a problem who the previous Christmas had publicly sworn to marry of Elizabeth of York should he become king, a matter that was gaining favour with disaffected Yorkists and in that same month the first of the marriage dispensations was granted. If Richard was going to spike that particular gun, he had to get hold of EoY and marry off to someone else but he had to get her out of sanctuary first, so what if he used the exclusion policy to achieve it? EW would have had very little choice, either accept Richard’s terms or be expelled.

There is of course some mystery as to why Richard didn’t marry her off immediately but the answer to that could lie in Rome. That first dispensation must have involved someone high up pulling strings and the Curia could hardly have been unaware of the situation in England at the time. What if the Curia had cause for grievance, the failure to refer the allegation of bigamy to a consistory court – on the subject of marriage including bigamy much reform had been brought in by Alexander III, who ruled that in cases involving marital separation or nullity, a minimum of two witnesses were required – and what would have been regarded a gross dereliction of duty on the part of Stillington? So who were the big noises in the Curia at the time? The Orsini family of Rome, descendants of King John and Simon de Montfort, one of whose members, Sueva, had been Jacquette of Luxembourg’s maternal grandmother which means of course, they were related to both EW and EoY and would hardly have been amused at what they would have perceived as Richard’s dastardly treatment of their relatives who also included Edward V and Richard of York. So what if Richard ended up with his own gun being spiked?

Finally a tip for those using the British Library. Out of preference I use the Rare Books and Music Reading Room rather than Humanities 1 which is on the same floor which I find more spacious, better lit and never a problem getting a seat. Only problem are the state documents which are kept in Humanities 1, but after a couple of hours I do feel the need to stretch my legs.

LikeLike

1. Warwick: why would Stillington tell him? Quite aside from the fact that Warwick’s brother replaced Stillington as Chancellor, there’s no indication that Warwick and Stillington were ever close.

2.Stillington in May, 1483: there might still have been, or seemed to be, hope that Gloucester, and Edward V/Woodvilles could reconcile. Remember, it is quite possible that Stillington would have been embarrassed by having to tell about the precontract. Arguably he may have been hoping to be able, in good conscience to England, to keep quiet.

3. I see no real indication, much less proof, that Richard ever intended to cast doubt on Edward IV’s legitimacy. It would be a real bad mistake to do so, and was quite unnecessary.

4. Any will of Cecily’s after 1485 could provide little for Richard III, who predeceased his mother by 10 years. Prayers perhaps, masses for soul, maybe even hope for a better burial place. Nothing else.

5. Edward IV’s death caught all by surprise. No poisoning there.

6. Would the Orsini really have been concerned about relatives that (literally) distant?

7. Margaret Beaufort: 65 years old, had lost her son. Absent strong indications, let’s not manufacture more murders.

LikeLike

Thanks for the discussion latrodecta and Richard McArthur. You both raise some very interesting theories and interpretations. Personally, I see both sides to every argument about the precontract between Eleanor and Edward IV, as the evidence isn’t clear-cut and is largely based on second-hand sources. It’s quite possible it was faked, and it’s quite possible it was genuine. If, in the future, someone found contemporary first-hand evidence that it was faked, then I will change my opinion accordingly. Currently, my viewpoint is that it was possible, that the Three Estates in 1483 accepted the evidence given by Stillington, including the learned churchmen who attended that gathering, and off the top of my head, I cannot recall any of them coming forward during Henry VII’s reign to retract their support of it. (Many of them had died, of course, but some – including Stillington – survived into the next reign, and there is no evidence that he felt compelled to protect his mortal soul from eternal damnation by retracting such a damnable perjury.)

Michael Hicks also says in his recent biography of Richard III that his 1483 coronation was remarkably well-attended, which suggests that the precontract had to have been – at a minimum – accepted to be true by those attending it. Some may argue that those attending it must have had secret “reservations” or “doubts”, but unfortunately we cannot see into their minds from this distant vantage point. It’s similar to how some might have had doubts about Henry IV’s accession and the deposition of Richard II, which – if we believe Henry IV’s first parliament – was based on the notion that Edward III was actually an illegitimate king as he was allegedly the second-born son. Obviously, people living in late medieval period had some capacity to “suspend disbelief” or to believe “fake news”.

If I could, I would like us to focus any future discussions on church court procedures, since this is what my original blog post was about. What inspired me to do this research was the argument, by some very serious historians and researchers, that Richard III’s accession was fatally flawed by the lack of reference of the precontract claim to an ecclesiastical tribunal. What I hope I’ve shown is that under church court procedures, it’s equally possible that an ecclesiastical tribunal would have reached the same result as the Three Estates in 1483. Richard Helmholz, in his analysis of the precontract claim and Titulus Regius, says that it presents a facially-valid claim of a precontract that would have made Edward IV’s sons by Queen Elizabeth, illegitimate.

So do you think the “two witness” rule in canon law procedure is a good mechanism to weed out genuine from fraudulent claims? Or, do you agree with John Fortescue that it’s inferior to the secular law procedure requiring 12 “good men” to attest to the facts?

LikeLike