It is generally acknowledged by historians that Henry Tudor, who defeated Richard III, the last Yorkist king, at Bosworth and went on to be crowned Henry VII, wasn’t the Lancastrian heir to the throne of England he claimed to be. His mother, Margaret Beaufort, was descended from John of Gaunt, the third surviving son of Edward III, but through an illegitimate line which, although it had been legitimised in the 1390s, was subsequently barred from the throne by the first Lancastrian king, Henry IV, Gaunt’s only surviving legitimate son by his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster. Moreover Gaunt had inherited the title Duke of Lancaster from Blanche’s father and the Beauforts were descended from his mistress Katherine Swynford, so had none of Blanche’s blood. After the deaths of Henry VI and his only son Edward (the first husband of Anne Neville, Richard’s queen) in 1471, the senior Lancastrian heirs to the throne of England were the kings of Portugal through Gaunt’s eldest legitimate daughter Philippa, followed by the descendants of his other legitimate children. Henry Tudor’s father Edmund, first earl of Richmond, was Henry VI’s half brother, but through their mother, the French princess Catherine of Valois. Edmund’s father Owen Tudor was a Welsh courtier, so Edmund had no royal English blood at all. Or did he?

Were The Tudors Really Tudors?

So asked popular historian Dan Jones in an article on History Extra, the website of BBC History Magazine, entitled “The 5 greatest mysteries behind the Wars of the Roses”. In it he describes the “foggy” origins of the Tudor dynasty:

“Their first connection to the English crown came through Henry VII’s grandmother, Catherine de Valois, widow of Henry V and mother of Henry VI. As dowager queen Catherine had caused quite a stir by secretly marrying her lowly servant, Owen Tudor. Plenty of romantic rumours have swirled around that union, but whatever the case, during the early 1430s Catherine gave birth to several children who took the Tudor name, most notably Henry VII’s father, Edmund Tudor, and another boy named Jasper Tudor.”1

So far, so factual. However, he then goes on to question the paternity of Edmund, Catherine’s eldest son:

“It has been speculated that Catherine’s marriage to the lowly Owen Tudor was contracted to cover up her politically dangerous relationship with Edmund Beaufort. In that case, is it possible that Edmund Tudor was not a Tudor at all, but was actually given the forename of his real father?”

Jones is not the first historian to raise this possibility. In his entry on Edmund Beaufort, first duke of Somerset, in the OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY Colin Richmond mused:

”It seems unlikely that Edmund Beaufort would have taken so great a political risk as getting the queen dowager with child, but he was a dashing young man (recently released from prison) as well as a Beaufort, and Catherine, who had fulfilled the only role open to her by immediately producing a son for the Lancastrian dynasty, was a lonely Frenchwoman in England, and at thirty or thereabouts was, the rumour ran, oversexed. Many stranger things have happened, and the idea of renaming sixteenth-century England is an appealing one.”2

Jones and Richmond both quote Gerald Harriss, who noted in his book “CARDINAL BEAUFORT: A STUDY OF LANCASTRIAN ASCENDANCY AND DECLINE”:

“By its very nature the evidence for Edmund ‘Tudor’s’ parentage is less than conclusive, but such facts as can be assembled permit the agreeable possibility that Edmund ‘Tudor’ and Margaret Beaufort ie Edmund Tudor’s wife and Henry VII’s mother were first cousins and that the royal house of ‘Tudor’ sprang in fact from Beauforts on both sides.”3

In his entry on Catherine of Valois in the OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, Michael Jones too pondered the possibility, but remained unconvinced:

”Many later legends developed to explain their remarkable romance: that Owen had been in Henry V’s service in the wars in France or in the royal household, that he had first attracted attention by falling into the queen’s lap in an inebriated state at a dance or when she and her ladies had espied him swimming, but nothing is certainly known to explain the start of their relationship. … The naming of their first child, Edmund Tudor, has also led to serious speculation on whether Henry VII, Edmund Tudor’s son, descended from Beauforts on both sides of his pedigree, though this seems improbable.”4

John Ashdown-Hill, on the other hand, has suggested that not only Edmund, but also his younger brother Jasper may have been fathered by Edmund Beaufort and dedicated an entire chapter in his book “ROYAL MARRIAGE SECRETS” to examining the possibility.5

Here at Ricardian Loons we are big fans of questioning the consensus, so let’s take a look at the evidence these historians have cited to support it. Do Dan Jones et al have a point?

The Claim

The father of Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, was not Owen Tudor, as is generally accepted, but Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset – a descendant of Edward III via his third son, John of Gaunt, and his mistress and later wife, Katherine Swynford.

The Evidence

1. Historical Documentation

The principal evidence cited by all above mentioned historians is contemporary historical documentation, or lack thereof. In a nutshell:

“Intriguingly, shortly before Catherine became involved with Owen, there was a widespread suggestion that she was having an affair with Edmund Beaufort, the future duke of Somerset, who would be killed at the battle of St Albans in 1455. This rumour was taken so seriously that parliament took up the matter and issued a special statute restricting the right of queens of England to remarry.”6

What we do know is that in the Parliament of 1426 the Commons had petitioned the Chancellor, Edmund Beaufort’s uncle Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester, to allow widowed queens of England to remarry a man of their choosing upon payment of a fine. As Michael Jones has pointed out, this most likely alluded to Catherine of Valois rather than to Joan of Navarre, who at this time was already in her fifties, and he, Dan Jones and Ashdown-Hill all interpret the petition, not unreasonably, as indicative of an affair between Catherine and Edmund Beaufort. Unfortunately for Catherine, the late king’s brothers John, Duke of Bedford, and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, opposed the petition and the statute which was eventually passed in the Parliament of 1427 – 1428 ruled that widowed queens could only remarry with the consent of an adult king. Failure to obtain this consent would result in the husband forfeiting his property:

“Item, it is ordered and established by the authority of this parliament for the preservation of the honour of the most noble estate of queens of England that no man of whatever estate or condition make contract of betrothal or matrimony to marry himself to the queen of England without the special licence and assent of the king, when the latter is of the age of discretion, and he who acts to the contrary and is duly convicted will forfeit for his whole life all his lands and tenements, even those which are or which will be in his own hands as well as those which are or which will be in the hands of others to his use, and also all his goods and chattels in whosoever’s hands they are, considering that by the disparagement of the queen the estate and honour of the king will be most greatly damaged, and it will give the greatest comfort and example to other ladies of rank who are of the blood royal that they might not be so lightly disparaged.”7

Given that the king, Catherine’s son Henry VI, was still a child, this effectively made it impossible for her to remarry anytime soon. Despite this bill – or perhaps because of it – around 1430 she started a relationship with Owen Tudor, which resulted in a number of children. As Michael Jones notes:

”It has even been suggested that she may have taken Tudor as her husband to prevent her true love, Edmund Beaufort, suffering the penalties of the statute of 1428, since Owen had so few possessions to forfeit.”

The couple and their children lived away from court and it is generally assumed that the relationship remained secret until after Catherine’s death in 1437 when Owen was imprisoned for having married her without permission, although Michael Jones believes that the court must have known about it by May 1432 when Owen was given the rights of an Englishman to protect him from anti-alien legislation.

Crucially though, there is no written record of their marriage and the exact date, as well as the date of birth of their first child, Edmund, are unknown. It is this which has given rise to the speculation around Edmund’s paternity. As Richmond explains:

”Almost everything is obscure about a liaison that resulted in a parliamentary statute regulating the remarriage of queens of England, but it is just possible that another of its consequences was Edmund Tudor. It is all a question of when Catherine, to avoid the penalties of breaking the statute of 1427–8, secretly married Owen Tudor, and of when the association with Edmund Beaufort came to an end. Neither of these dates, as might be expected, is known; nor is the date of birth of Edmund Tudor.”

Ashdown-Hill goes further and questions whether they ever married at all. In addition to the documentation mentioned above, he presents several new pieces of evidence to support his idea.

Firstly, he alleges more than once that Edmund Beaufort didn’t marry Eleanor Beauchamp until after Catherine’s death in 1437.

Secondly, he points to the fact that at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries Edmund’s grandson, Henry VIII, rescued only the remains of his grandfather Edmund (and his sister Mary Tudor) from the churches where they had been buried, but not those of his great-grandfather Owen. He argues that this is because, if Edmund had been the son of Edmund Beaufort, then Henry would have had no real family connection with Owen.

His third piece of evidence is a proclamation made by Richard III against Henry Tudor, Edmund’s son, which claimed that he was of bastard descent. He argues that:

“If Richard was speaking of Henry’s maternal Beaufort descent then his use of the word bastard was not strictly accurate, since the Beauforts had been legitimised. However, if Richard III’s words were a veiled allusion to the belief that Henry VII’s father was the illegitimate son of Catherine of France by Edmund Beaufort, then his allegation of bastard descent, albeit unproven (and in those days unprovable), was possibly accurate.”

2. Heraldry

Ashdown-Hill’s fourth piece of evidence are the heraldic arms of Edmund Tudor and his younger brother Jasper. He believes they show that both boys were fathered not by Owen Tudor, but Edmund Beaufort:

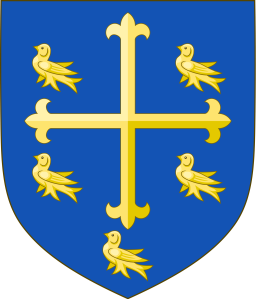

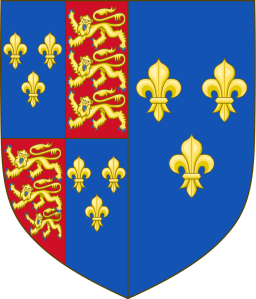

“There is no written evidence available in the case of either Edmund or Jasper to help us resolve the question of paternity. Nevertheless, there is clear evidence of a different kind, though its significance has been hitherto overlooked. This evidence takes the form of heraldry. Coats of arms belong to individuals, not to families. Nevertheless the sons of an armigerous father are allowed to use versions of the father’s coat of arms, marked by some point of difference, called a mark of cadency. During the Plantagenet period marks of cadency sometimes took the form of a ‘bordure’ (coloured surround or border) added to the father’s arms. Thus, for example, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainaut, bore his father’s arms with the addition of a silver (or white) bordure. Similarly, after his legitimisation, John Beaufort, the eldest son of John of Gaunt, bore the English royal arms, surrounded by a blue and silver (or white) bordure as a mark of cadency. This coat of arms was later inherited by Edmund Beaufort (see Plate 6). Sons of Edmund Beaufort would have been entitled to use the same arms, but with some change in the colour or design of the bordure. Owen Tudor also bore a coat of arms. However, it was nothing like the royal arms, and there was no reason why it should have been. Owen’s shield was red in colour, and bore a chevron coloured ermine, surrounded by three helms in white or silver (see Plate 5). If Edmund and Jasper Tudor were Owen Tudor’s sons they should have borne a version of the same coat of arms as their father, with some mark of difference – either a coloured bordure or a label. But, astonishingly, neither Edmund nor Jasper Tudor used arms remotely resembling those of Owen Tudor. Instead both brothers bore the royal arms with a blue bordure, marked in Edmund’s case with alternate golden martlets (heraldic birds) and fleurs de lis, and in Jasper’s case, with gold martlets only (see Plates 7 and 8). These coats of arms, which owed nothing whatever to the arms of Owen Tudor, were clearly derived from the arms of Edmund Beaufort. The blue and gold bordures of Edmund and Jasper Tudor were simply versions of the blue and white bordure of Edmund Beaufort, modified for cadency. Apart from this modification the three coats of arms were identical. The arms of Edmund and Jasper Tudor, which were entirely appropriate for putative sons of Edmund Beaufort (who would, via that paternity, have inherited some English royal blood), were wholly inappropriate for sons of Owen Tudor (who would have had no single drop of English royal blood in their veins). The whole purpose of medieval heraldry was to show to the world who one was. And the coats of arms of Edmund and Jasper Tudor proclaimed, as clearly as they could, that these two ‘Tudor’ sons of the queen mother were of English royal blood, while their bordures suggest descent from Edmund Beaufort. The only possible explanation seems to be that Beaufort was their real father.”

The arms of Owen Tudor

The Beaufort arms

Does It Stack Up?

There can be no doubt that the marriage between Catherine of Valois and Owen Tudor was either secret or didn’t take place at all since, as noted above, the king who had to give his consent was only a child. The facts point to a secret marriage, which was not uncommon in the Middle Ages, even among the nobility. Interestingly, this includes the marriage of Edmund Beaufort and Eleanor Beauchamp which, as both Richmond and Ashdown-Hill point out, was only pardoned and granted recognition in 1438. However, Ashdown-Hill’s assertion that they didn’t marry until after Catherine’s death in 1437 is contradicted by Richmond, who claims that they married before 1436. Neither historian specifies his source, but several of their children are thought to have been born between 1431 and 1436, which suggests that they were indeed married by then (Eleanor’s first husband Thomas, Lord Ros, had died in 1430).

Secondly, it’s true that Henry VIII rescued only the remains of his grandfather Edmund at the dissolution of the monasteries, but not those of his great-grandfather Owen, but Ashdown-Hill admits himself that Henry “did very little to rescue any royal burials from the doomed churches”.

Thirdly, Ashdown-Hill is absolutely correct that it was inappropriate for the Tudor brothers to difference the royal arms of England – they had some claim to the royal French arms as their mother Catherine of Valois was the daughter of Charles VI of France, but they didn’t have any royal English blood. However Henry VI, the king who granted them their earldoms, was not only their half brother, but also weak and easily influenced. As John Watts has noted, “it is difficult to escape the conclusion that he simply endorsed all requests put before him. This was certainly the implication of various conciliar initiatives to stem the flood of royal generosity. It is also suggested by the preponderance of grants to those enjoying most continuous access to the king, by the tendency for grants to particular people to be concentrated on occasions when we know them to have been at Henry’s side, by the notorious royal propensity for granting the same thing more than once and by the developing practice of granting reversions once the original stock of patronage was exhausted.”8

For example, he granted the stewardship of the Duchy of Cornwall to both Sir William Bonville and the Earl of Devon, thereby starting the Bonville-Courtenay feud. Henry’s generosity appears to have also extended to titles. As Christine Carpenter has pointed out, “Buckingham himself owed his dukedom in 1444 to the elevation of nobles related to the royal house. The young Henry Beauchamp, earl of Warwick, also made duke in 1444, despite the absence of any blood relationship to the crown, was favoured in his brief period of adulthood from 1444 to 1446.”9

It’s easy to imagine Henry granting his half brothers not just earldoms, but also royal arms if they lobbied hard enough for it. They certainly appear to have been on good terms with him. They were appointed his advisors, endowed with lands and jointly granted the wardship and marriage of Margaret Beaufort, one of England’s wealthiest heiresses, whom Edmund eventually married.

Crucially though, at least two historical documents exist which name Owen Tudor as father of both Edmund and Jasper.

The first document is the Act of Parliament of 1454, which confirmed the charter creating them Earls and emphasises their close relationship to Henry VI:

“To the most excellent and most Christian prince our lord the king, we the commons of this your realm, most faithful subjects of your royal majesty, in your present parliament assembled; in order that there may be brought before the most perspicacious eyes of royal consideration the memory of the blessed prince, Queen Catherine your mother, by whose most famous memory we confess we are very greatly affected, chiefly because she was worthy to give birth by divine gift to the most handsome form and illustrious royal person of your highness long to reign over us, as we most earnestly hope, in glory and honour in all things; for which it is necessary to acknowledge that we are most effectively bound more fully than can be said not only to celebrate her most noble memory for ever, but also to esteem highly and to honour with all zeal, as much as our insignificance allows, all the fruit which her royal womb produced; considering in the case of the illustrious and magnificent princes, the lords Edmund de Hadham and Jasper de Hatfield, natural and legitimate sons of the same most serene lady the queen, not only that they are descended by right line from her illustrious womb and royal lineage and are your uterine brothers, and also that by their most noble character they are of a most refined nature – their other natural gifts, endowments, excellent and heroic virtues, and other merits of a laudable life and of the best manners and of probity we do not doubt are already sufficiently well known to your serenity – that you deign from the most excellent magnificence of your royal highness to consider most kindly how the aforesaid Edmund and Jasper, your uterine brothers, were begotten and born in lawful matrimony within your realm aforesaid, as is sufficiently well known both to your most serene majesty and to all the lords spiritual and temporal of your realm in the present parliament assembled, and to us; and on this, from the most abundant magnificence of royal generosity, with the advice and assent of the same lords spiritual and temporal, by the authority of the same to decree, ordain, grant and establish that the aforesaid Edmund and Jasper be declared your uterine brothers, conceived and born in a lawful marriage within your aforesaid realm, and denizens of your abovesaid realm, and not yet declared thus.”10

The Act clearly describes both Edmund and Jasper as ”legitimate” and “begotten and born in lawful matrimony” (“Edmundus & Jasper, Fratres vestri uterini, in legitimo matrimonio, infra Regnum vestrum predictum procreati & nati existunt”).

The second document is the proclamation made by Richard III on 28 June 1485 against Edmund’s son, Henry Tudor (later Henry VII), who was laying claim to Richard’s throne, which states that “the seid rebelles and traitours have chosyn to be there capteyn one Henry Tydder, son of Edmond Tydder, son of Owen Tydder, whiche of his ambicioness and insociable covetise encrocheth and usurpid upon hym the name and title of royall astate of this Realme of Englond, where unto he hath no maner interest, right, title, or colour, as every man wele knoweth; for he is discended of bastard blood bothe of ffather side and of mother side, for the seid Owen the graunfader was bastard borne, and his moder was doughter unto John, Duke of Somerset, son unto John, Erle of Somerset, sone unto Dame Kateryne Swynford, and of ther indouble avoutry (adultery) gotyn.” It also condemns “Jasper Tydder, son of Owen Tidder, calling himself Earl of Pembroke”.11 It’s unclear if this is the proclamation Ashdown-Hill refers to as evidence for Edmund’s illegitimacy as he doesn’t specify his source, but here Richard clearly names Owen Tudor as father of both Edmund and Jasper and the allegation of illegitimacy actually refers to Owen’s paternity, not theirs.

Ashdown-Hill – and indeed all proponents of the Beaufort paternity – also overlooks the fact that, if Edmund’s father had been Edmund Beaufort, then not only would Henry Tudor’s father have been illegitimate, but his parents would have been first cousins and married without the papal dispensation required for this degree of consanguinity as his mother was Margaret Beaufort, only daughter of John, Duke of Somerset. Given that Henry was laying claim to the throne of England it would have been in Richard’s interest to draw attention to this arguably even greater flaw in Henry’s pedigree, but he didn’t.

One last possibility remains: could Edmund and Jasper have sneakily differenced the Beaufort arms and passed them off as royal arms? Technically yes and it is interesting that the bordure Azure on both Edmund’s and Jasper’s arms is charged with martlets Or since the arms posthumously attributed to Edward the Confessor are Azure, a cross flory between five martlets, all Or, while the fleurs-de-lys Or alternating with the martlets on Edmund’s bordure are clearly a reference to Catherine’s royal arms of France.

The arms attributed to Edward the Confessor

The arms of Catherine of Valois

However, although they briefly sided with Richard, Duke of York against Henry VI in the early stages of the Wars of the Roses, which could be interpreted as a sign that their relationship with their half brother wasn’t as close as described in the petition to Parliament, there is no indication that their contemporaries suspected them to be the sons of Edmund Beaufort or that they coveted the throne for themselves. This was left to Edmund’s son Henry Tudor who, despite his flawed pedigree, initially claimed the English throne by “rightful claim, due and lineal inheritance”12 and in a letter by the French king Charles VIII to the town of Toulon was even described as Henry VI’s son.13 However, he never claimed to be the grandson of Edmund Beaufort. It could be argued that he didn’t need to as he had inherited the royal English blood of Edward III through his mother, Margaret Beaufort, but as the Beauforts were barred from the throne it is doubtful how strong this claim really was. It certainly didn’t impress Richard III, who dismissed them as bastards in his proclamation. Even Henry himself didn’t solely rely on his Beaufort credentials. He ultimately claimed the throne by right of conquest and then married Elizabeth of York, the eldest daughter of Richard’s brother, Edward IV.

Conclusion

It’s unlikely that Edmund Tudor was the son of Edmund Beaufort. Richard III’s proclamation clearly identifies both him and his brother Jasper as the sons of Owen Tudor and Henry VI’s Act of Parliament refers to them as legitimate. While Henry was a weak king who could have been influenced by his half brothers, this can’t be said about Richard. On the contrary, his proclamation is credible not only because it corroborates Henry’s narrative, but because it does so against his own interest of exploiting the flaws in Henry Tudor’s pedigree. As the man who established the College of Arms and, prior to this accession to the throne, active soldier and long-serving Constable of England and therefore presiding judge of the Court of Chivalry, Richard would have been ideally placed to spot evidence of an illicit affair between Catherine of Valois and Edmund Beaufort in Edmund and Jasper Tudor’s arms, but he said nothing. He wasn’t shy when it came to accusing his enemies of misdeeds – aside from rubbishing Henry’s pedigree he claimed that his supporters were murderers, adulterers and extortionists who would commit the “most cruell murders, slaughterys, and roberys, and disherisons that ever were seen in eny Cristen reame” should they succeed in their attempt to topple him14 – so why keep silent about a prohibited degree of consanguinity?

The logical conclusion has to be that Catherine and Owen really were married, albeit secretly, and that Edmund and Jasper really were their sons. The most likely explanation for their inappropriate coats of arms is that they were a result of being on good terms with Henry VI, if not active lobbying on their part. As Ashdown-Hill himself points out, “the whole purpose of medieval heraldry was to show to the world who one was”, so why bear the differenced arms of a Welsh courtier if you can bear those of a king?

Sources & Further Reading

-

Dan Jones: “The 5 greatest mysteries behind the Wars of the Roses”, History Extra website (7 January 2016) http://www.historyextra.com/article/military-history/mysteries-wars-roses-Dan-Jones

-

John Ashdown-Hill, “ROYAL MARRIAGE SECRETS”, The History Press (2013)

-

Colin Richmond, “Beaufort, Edmund, first duke of Somerset (c.1406–1455)”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2008) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1855

-

Michael Jones, “Catherine (1401–1437)”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2008) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4890

-

R. A. Griffiths, “Henry VI”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2015) http://www.oxforddnb.com/index/12/101012953

-

R. S. Thomas, “Tudor, Edmund, first earl of Richmond”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2015) http://www.oxforddnb.com/index/27/101027795/

-

R. S. Thomas, “Tudor, Jasper, duke of Bedford”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2008) http://www.oxforddnb.com/index/27/101027796/

-

John Watts, “HENRY VI AND THE POLITICS OF KINGSHIP”, Cambridge University Press (1999)

-

Nigel Ramsay, “Richard III and the Office of Arms”, PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2011 HARLAXTON SYMPOSIUM, ed. H. Kleineke and C. Steer, Shaun Tyas and the Richard III and Yorkist History Trust (2013)

-

The Anne Boleyn Files, “Helen Castor’s Medieval Lives: Birth, Marriage, Death – Episode 2: A Good Marriage” https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/helen-castors-medieval-lives-birth-marriage-death-episode-2-good-marriage/

- Dan Jones: “The 5 greatest mysteries behind the Wars of the Roses”, History Extra website (7 January 2016) http://www.historyextra.com/article/military-history/mysteries-wars-roses-Dan-Jones ↩

- Colin Richmond, “Beaufort, Edmund, first duke of Somerset (c.1406–1455)”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2008) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1855 ↩

- G. L. Harriss, “CARDINAL BEAUFORT: A STUDY OF LANCASTRIAN ASCENDANCY AND DECLINE”, Clarendon Press (1988) ↩

- Michael Jones, “Catherine (1401–1437)”, OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY (2008) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4890 ↩

- John Ashdown-Hill, “ROYAL MARRIAGE SECRETS”, The History Press (2013) ↩

- Dan Jones: “The 5 greatest mysteries behind the Wars of the Roses”, History Extra website (7 January 2016) http://www.historyextra.com/article/military-history/mysteries-wars-roses-Dan-Jones ↩

- The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, 1275-1504, Scholarly Digital Editions; CD-ROM edition (2005) ↩

- John Watts, “HENRY VI AND THE POLITICS OF KINGSHIP”, Cambridge University Press (1999), p. 154 ↩

- Christine Carpenter, “THE WARS OF THE ROSES: POLITICS AND THE CONSTITUTION IN ENGLAND, C.1437-1509, Cambridge University Press (2008), p. 106 ↩

- The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, 1275-1504, Scholarly Digital Editions; CD-Rom edition (2005) ↩

- James Gairdner (ed.), “THE PASTON LETTERS”, London 1872-5 (3 vols), vol. 3, pp. 316—20, cited by P. W. Hammond and Anne F. Sutton, “RICHARD III: THE ROAD TO BOSWORTH FIELD”, Constable (1985), pp. 208-10 ↩

- British Library Harleian MS 787, f.2, cited by Annette Carson, “RICHARD III: THE MALIGNED KING”, The History Press (2013), p. 284 ↩

- “Fils du feu rey Enry d’Angleterre”, A. Spont, “La marine française sous le règne de Charles VIII”, REVUE DES QUESTIONS HISTORIQUES, new series, II (1894), p. 393, cited by Annette Carson, “RICHARD DUKE OF GLOUCESTER AS LORD PROTECTOR AND HIGH CONSTABLE OF ENGLAND”, Imprimis Imprimatur (2015), p. 40 ↩

- “PASTON LETTERS”, vol. 3, pp. 316—20, cited by P. W. Hammond and Anne F. Sutton, “RICHARD III: THE ROAD TO BOSWORTH FIELD”, Constable (1985), pp. 208-10 ↩

There is a small error in the first line of the section headed Does it stack up? You have Catherine marrying Edmund Tudor rather than Owen.

A very interesting article – I had not known that other historians besides John Ashdown Hill, had considered the idea that some or all of the Tudor children might have been fathered by Edmund Beaufort.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops! Thank you very much – fixed!

LikeLike

Excellent read the research into the matter is intensive

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much!

LikeLike

John Ashdown-Hill’s argument that Edmund and Jasper were the sons of Edmund Beaufort, based on heraldry is flawed, due to errors and omissions. The familiar Beaufort arms, “inherited by Edmund Beaufort,” were granted only after the accession of John Beaufort’s half-brother, Henry of Bolingbroke, as Henry IV. This is why they take the form of “the English royal arms,” quartered with arms of France, acknowledging John’s relationship with the new king, and “surrounded by a blue and silver (or white) bordure as a mark of cadency.”

The arms borne by John Beaufort “after his legitimisation”, by Richard II, took a different form – not mentioned by Ashdown-Hill. – which used only the arms of England (the Three Lions):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Beaufort,_1st_Earl_of_Somerset#/media/File:Arms_of_John_Beaufort,_1st_Earl_of_Somerset_(Bastard).svg

LikeLike

The arms borne by John Beaufort … which used only the arms of England (the Three Lions):

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arms_of_John_Beaufort,_1st_Earl_of_Somerset_(Bastard).svg

LikeLike

Correction:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arms_of_John_Beaufort,_1st_Earl_of_Somerset_(Bastard).svg

LikeLike

Ashdown-Hill is partly correct when he suggests that Edmund and Jasper Tudor, as Owen Tudor’s sons, each “should have borne a version of the same coat of arms as their father, with some mark of difference – either a coloured bordure or a label.” (But because they lacked lands of their own until they received grants by Henry VI, the usual evidence for coats of arms from seals attached to charters issued in their own right, for instance as lord of a manor, seem to be missing.)

Ashdown-Hill’s chief mistake is to insist that the arms later borne by Edmund and Jasper, “were clearly derived from the arms of Edmund Beaufort,” implying that they were his sons, If this were true they should shared the same heraldic colours, “azure” and “argent”, blue and silver. Instead the bordure on each of their coat of arms was plain blue (“azure”) with devices – fleurs-de-lys and martlets – in gold (“or”). Their coats of arms were granted to mark their relationship as half-brothers to the king – Henry VI – and not as natural sons of Edmund Beaufort. This followed the precedent of John Beaufort and Henry IV.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for your comment and the additional info. I agree, Ashdown-Hill is right in that you’d expect Owen Tudor’s sons to differentiate his arms, but his argument around the Beaufort arms is flawed.

LikeLike

A very small and trivial point. Henry Duke of Warwick did have “royal” blood. He was descended from Edmund of Langley through Constance of York and Isabelle Despenser (his mother). Isabelle was first cousin to Richard, Duke of York. Whether this had any relevance to his receiving a dukedom, I know not.

LikeLike